One of my favorite writers of yesteryear is Hal Boyle (1911-1974), a colorful and witty AP award-winning journalist who frequently wrote about Appalachia. Typical of the writer’s work is a 1955 article commenting about how modern factories were affecting the lifestyle of residents of the Great Smoky Mountains.

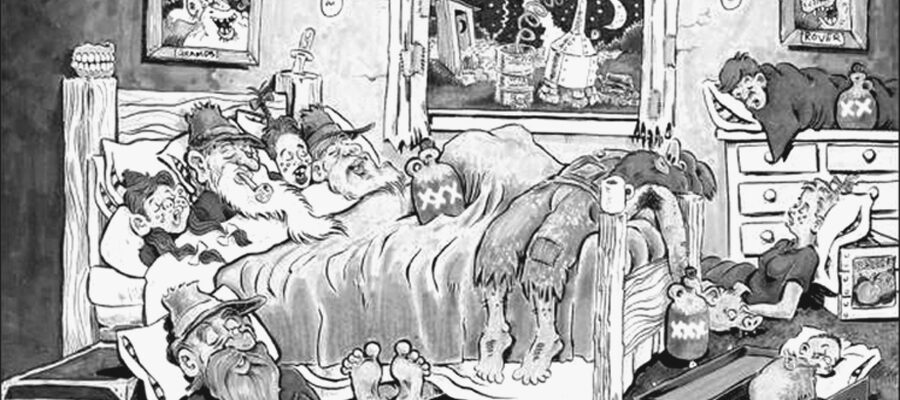

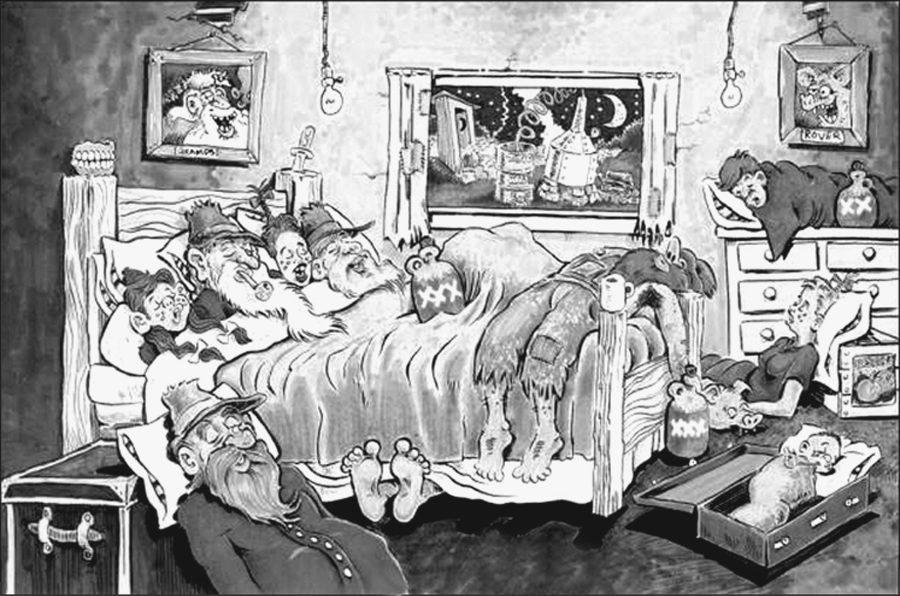

The fictional stereotyped hillbilly was portrayed as a shiftless figure wearing overalls who ran through the hills barefooted, a worn guitar slung over his shoulder, an old hog rifle in one hand and a jug of moonshine in the other. According to Boyle, the hillbilly image began to change over time.

Mountain folks began adapting to a new way of life that enabled them to maintain their ancient pastoral freedom while escaping the paucity of the past. They were enjoying the best of both worlds. Hal noted that the mountaineers humorously portrayed a distorted image for tourists to enjoy. However, they didn’t relish a ‘flatland furriner’ (city dweller) calling them a ‘hillbilly,’ preferring instead to be referred to by more dignified terms as southern highlander, mountain man, hill man or mountaineer.”

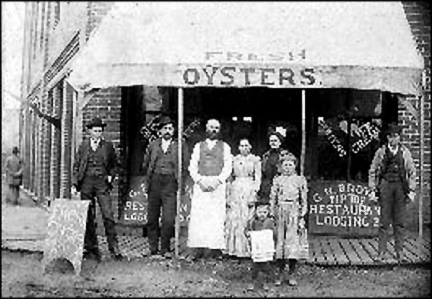

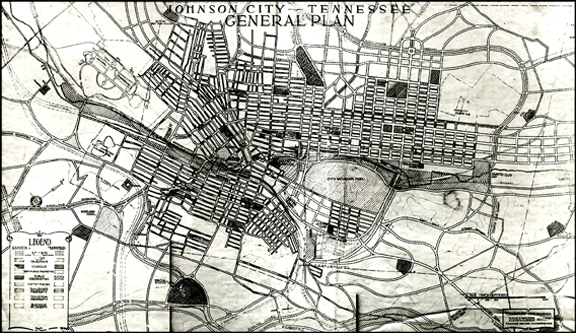

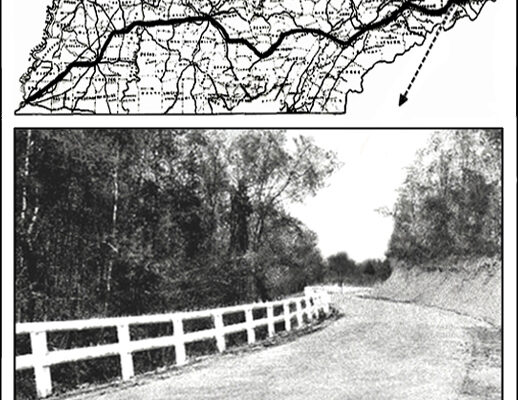

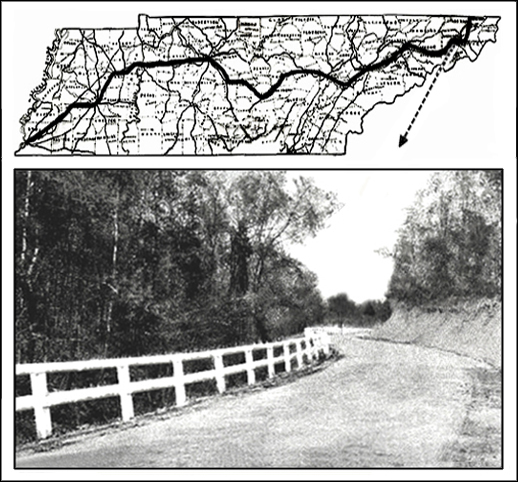

The industrialization of the Tennessee Valley changed the area from being so remote that vehicles could scarcely penetrate it to having adequate roads for travel. With it appeared improved social and economic patterns.

The mountain folks’ newly acquired skills ultimately brought them down from the hills to work at one of the growing number of factories in the valleys. Most of them opted to live in the mountains and work in the valleys. According to Boyle, “Some drove as much as 50 miles to their places of employment. When the quitting whistle blew, they climbed into their cars and drove back to their mountain homes to do their chores and cultivate their hillside gardens.”

Boyle related the case of a 43-year-old blacksmith who worked at Alcoa Aluminum Plant in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains, within sight of Chilhowie Mountain a few miles to the south of it. William, as I will call him, drove 10 miles to work from his 12-acre mountain farm where he, his wife and six children lived and farmed.

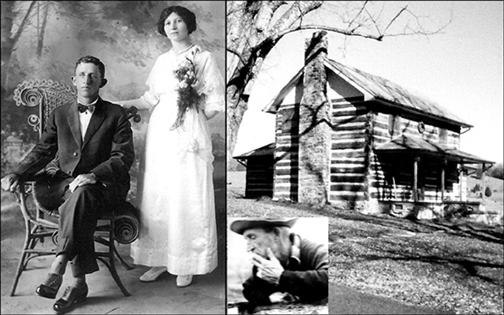

Although the mountaineer eventually could afford the comforts of living in the city, he was not willing to move there even if he were offered him a house that included multiple indoor bathrooms with modern plumbing. He was fully aware that prosperous times were rapidly changing mountain living. Most residents no longer lived in rustic cabins. They chose not to live in the cities because they could bring the amenities of city living back to their quaint mountain homes. Mountaineers began enjoying the comforts of electricity for heating, cooking and powering a wide variety of electrical devices such as radios and televisions.

William spoke highly of living in the hills: “There's an $80,000 school going up in my neighborhood. Why should I want to live in town? You know, I've never had a haircut, shave or shoeshine in town in all my days. The country's the best place to live and to raise a family. The people learn how to work and save and they don't get into so much trouble. My children have no desire to live in town.”

William acknowledged that there were still a few revenuer agents around chasing moonshine stills: “The growth of factory jobs has cut it down. When I was a boy, you could count seven stills from where I lived, but now there isn't one.”

The mountain man was very proud that he had retained the rugged independence and individualism of his ancestors. He achieved a degree of economic security they never knew and still enjoyed the lifestyle, sunshine and pristine air of the mountains. The “hillbilly” shifted toward becoming a “mountain william” but never a “citybilly.”