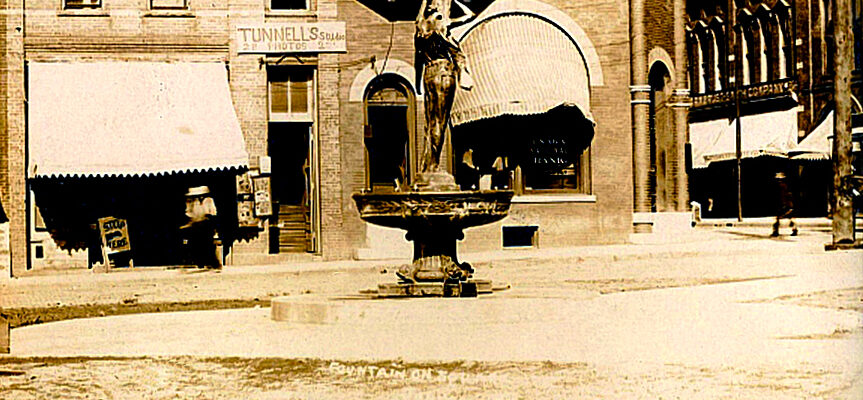

Few area residents can remember Johnson City’s grand “Lady of the Fountain,” who once adorned the downtown area along the east side of the railroad tracks. Over time, she became an icon, overlooking the very vicinity that would later bear her name, Fountain Square.

While her history is a bit blurred from a dearth of accurate record keeping, sufficient information exists that offers a hint of her once colorful past.

The lady, an imposing six-foot solid bronze statue, stood barefooted on a pedestal in the center of a three-foot tall circular concrete multi-spigot water fountain, facing southeast toward the Unaka National Bank building on Main Street.

Through the years, many a weary traveler has navigated through the city’s central business district, pausing just long enough to imbibe from her cool refreshing fountain. Several small pans situated around the base collected runoff water, further supplying water for horses and small animals.

This beautiful yet unsmiling melancholic lady was always modestly dressed in apparel resembling a Roman toga with sash, wearing earrings and a bracelet, Roman style “rolled” hair, and holding a large urn behind her right shoulder.

Considering her long exposure to the cold East Tennessee winters, her somewhat scantily clad garments were a bit surprising, perhaps accounting for her slate blue appearance. The hard-working townspeople were attracted to their pretty “fountain lady,” possibly because of her plaintive and unassuming subservient appearance.

It is believed that the shoeless beauty became a part of the city about 1904, soon after “Mountain Home,” known as “a city within a city,” was built. One conjecture suggests that then Mayor James Summers and other city officials sought a way to honor Congressman Walter Preston Brownlow of Tennessee's First District, U.S. House of Representatives (1896-1910), nephew of controversial governor, William “Parson” Brownlow.

The popular congressman was largely responsible for Johnson City being selected as recipient of the “Mountain Branch of the National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Veterans,” from an Act of Congress dated January 28, 1901.He had sympathized with the plight of thousands of Union Civil War (and later Spanish-American War) veterans, maimed during the four-year conflict and shamefully reduced to mere homeless beggars.

The city fathers reportedly chose to honor Brownlow with a statue to be placed in the heart of their town. After fabrication in a Lenoir City foundry and delivery to the city, the “Lady of the Fountain” reigned in the downtown district over the next approximately thirty-three years, observing the city’s colorful history unfold before her very eyes and ears.

In 1905, the lady watched in shock as the buildings along the south end of Main Street, between Roan Street and Spring Street, burned with one notable exception – the little wooden First Baptist Church. In 1908, she witnessed improvements made for downtown transportation by the paving of the streets with brick.

In 1918, the modest lady celebrated as the Armistice Day (Veteran’s Day) parade marched down Main Street, honoring the return of our soldiers from World War I. Over the years, the lady saw private transportation slowly transform from horse to horse-driven wagon and automobile, and public conveyance from trolley to bus, cab, and train. She routinely viewed busy shoppers, especially on Saturdays, as they crowded into the shops along Fountain Square.

Just when things couldn’t get much better, they got worse. Fate struck the unpretentious lady about 1937 when the city needed to alter parking and traffic flow around Fountain Square, necessitating the use of the site where the statue stood. Workmen came and abruptly separated her from the fountain she had always known.

While the base was summarily discarded, she was spared the same destiny, instead being relocated to the north entrance side of Roosevelt Stadium (now Memorial Stadium). Ironically, this occurred at about the same time that Lady Massengill and her family were arriving in town in the form of another statue, then located at the “Y” intersection of the Kingsport and Bristol highways.

No longer being the “Lady of the Fountain”, the statue observed very little goings-on in her new location, except for occasional sporting events. The hurrying crowds who passed by her scarcely gave her a glance.

No longer able to provide refreshing water to thirsty pedestrians, she sensed that the populace had forgotten the rationale for bringing her to the city many years prior. Life had become very different and extremely lonely for the former Lady Fountain.

The lady’s tenure at Roosevelt Stadium would prove to be a short one. In about 1943, city officials decided to replace her with yet another statue, a World War I Doughboy.

The city apparently had no plans for the lady, as she quietly vanished to the city dump, without anyone noticing or even caring what had happened to her.

Such an action demonstrated her true current worth to the city that had adopted her. That was no way to treat a lady.

The lady was soon rescued from the trash heap and temporarily stored in a barn along Watauga Avenue.

By 1951, the lady was adorning a flower garden at a home in Henderson, North Carolina, where she would remain for the next roughly thirty-two years. The confused statue was now living outside the very state that had acquired her as a tribute to a U.S. congressman.

The year 1973 brought renewed interest in the statue. The local Chamber of Commerce began efforts to retrieve her from her garden home, but initial efforts failed because the new owners were not willing to part with her.

There was another problem; the lady had fallen into poor “health” with elongated cracks forming along her legs. Her “doctors” made an effort to restore her health by improperly filling the cracks in her legs with concrete and painting over her characteristic slate blue appearance, demonstrating gross malpractice on their part. That was no way to treat a lady.

When the owners finally agreed to part with the attractive statue, the city immediately procured her, returned her to Johnson City, and began efforts to restore her to her original condition.

A Carter County high school teacher and sculptor, along with her students, carefully stripped the paint, removed the concrete, and properly filled the cracks, giving the lady the look of her former identity when she once graced downtown’s Fountain Square.

The city showed some long overdue respect for their lady when they declared September 20, 1983 as “Lady of the Fountain Day.” Now, that’s the way to treat a lady. After residing in an academic environment of the old Johnson City Public Library for several years, she now stands in the downtown Municipal and Safety Building’s lobby.

The lady has played an important role in Johnson City’s magnificent past, but the question begs to be answered… “What role will she play in the city’s uncertain future?”

Has the ageless beauty been retired to the comfort and serenity of a government building, or will she once again be prominently displayed where she can reclaim the attention and admiration of future generations of Johnson Citians? Time will tell.