Jay “Terry” Prater, an avid fan of the Johnson City History/Heritage page, has been in the ministry for over 50 years. He has pastored churches in several states, along with East Park and Oakland Avenue Baptist churches in Johnson City. He recently shared some photos from his early years in Johnson City.

The Praters moved here from Weaverville, NC in 1951. They took up residence on W. Maple St., attending South Side and Junior High schools. For extra cash, he worked about three years (1956-58) as a curb hop at the well-known Shamrock that opened in 1929 on W. Walnut Street. In his words, “I spent my younger years doing what kids normally do.”

Prater had several newspaper articles and photos relating to his Southside School days that he believed might be of interest to Heritage/History page readers.

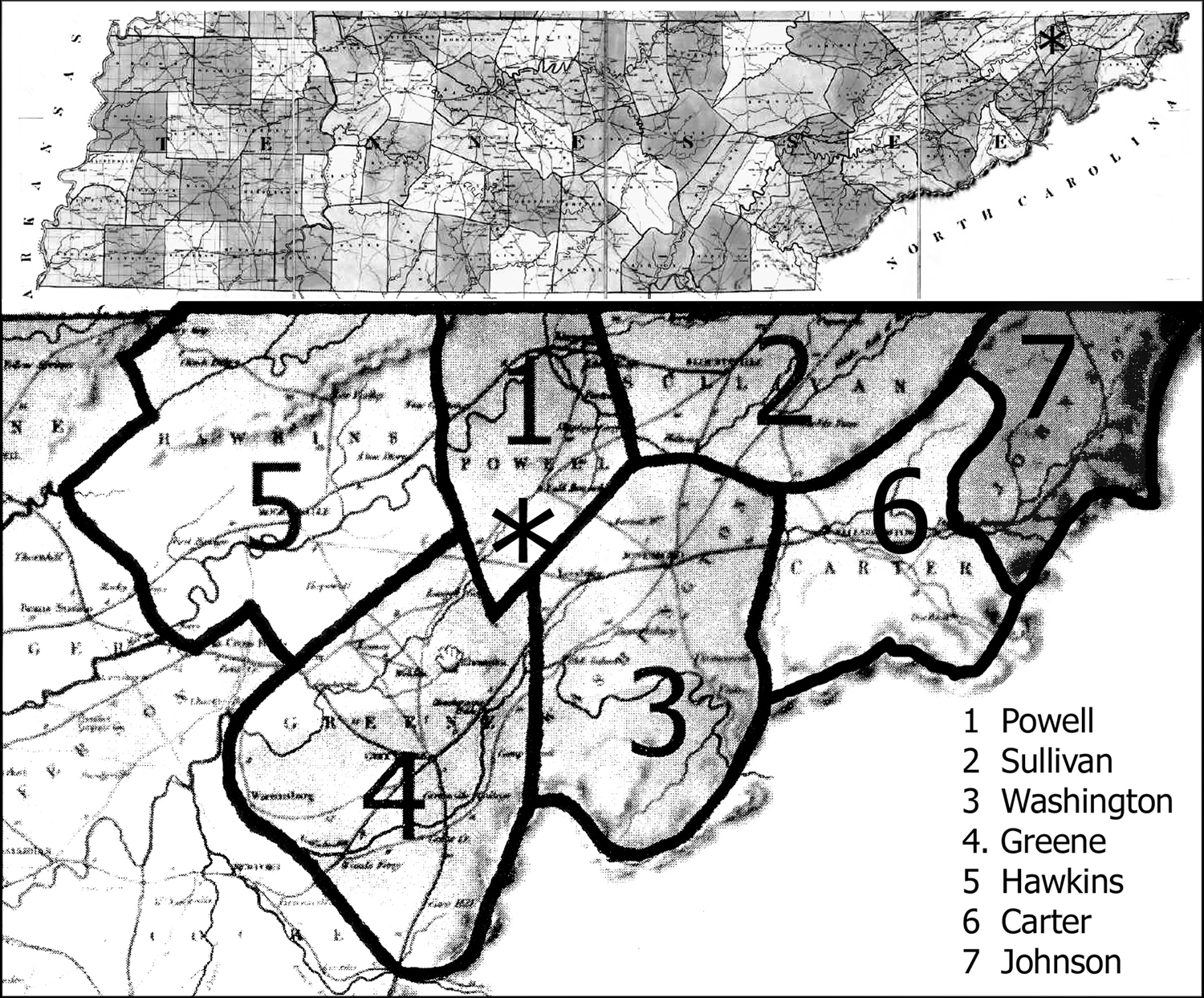

Photo 1

The original front side of old Southside Elementary School stands majestically in 1991 prior to it's demolition. The school faced Southwest Avenue, as well as Boyd Street.

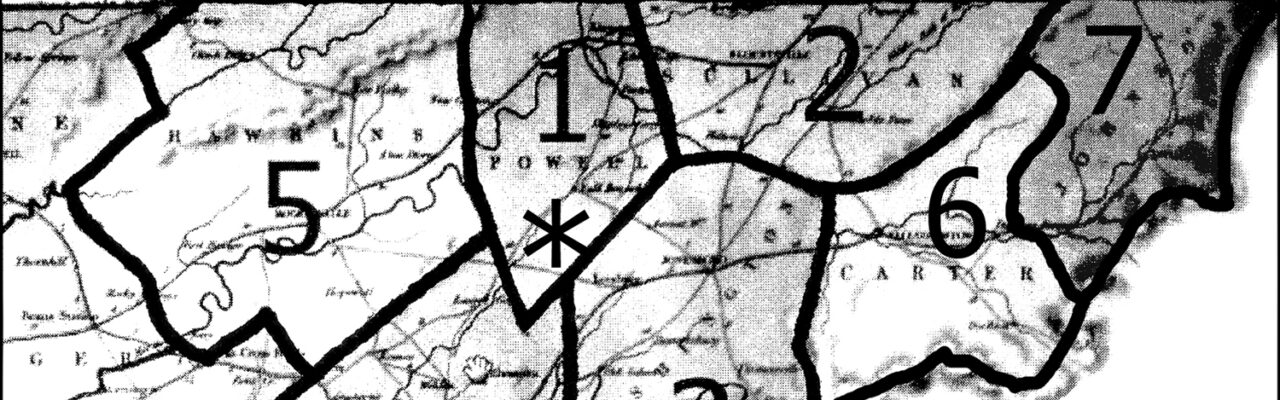

Photo 2

The front yard of South Side School was the setting in 1955 for a donation of school safety patrol equipment from E.B. Mallory (left) representing the Kiwanis Club. Accepting the gifts were two student traffic patrol officers, Capt. Wilbur Johnson and Lieut. Charles McCracken. Jay, 9th individual from the left, was in Mrs. Nola Dillow's6th grade class.He surmised that other students in the picture were from the 4th or 5th grades.

Paul Odom, a well-known officer of the Johnson City Police Department, was also on hand that day to assist with the presentation. Jay viewed the event as an honor to be a grade school student working with city police. “My patrol assignment was at the corner of W. Poplar and Boyd streets on the upper side of the school,” he said. “We had hats, a vest strap and a genuine official chrome badge. The one displayed is the photo is the one I proudly wore while at my post before and after school each day”. Jay asked if Press readers could identify others in the picture.

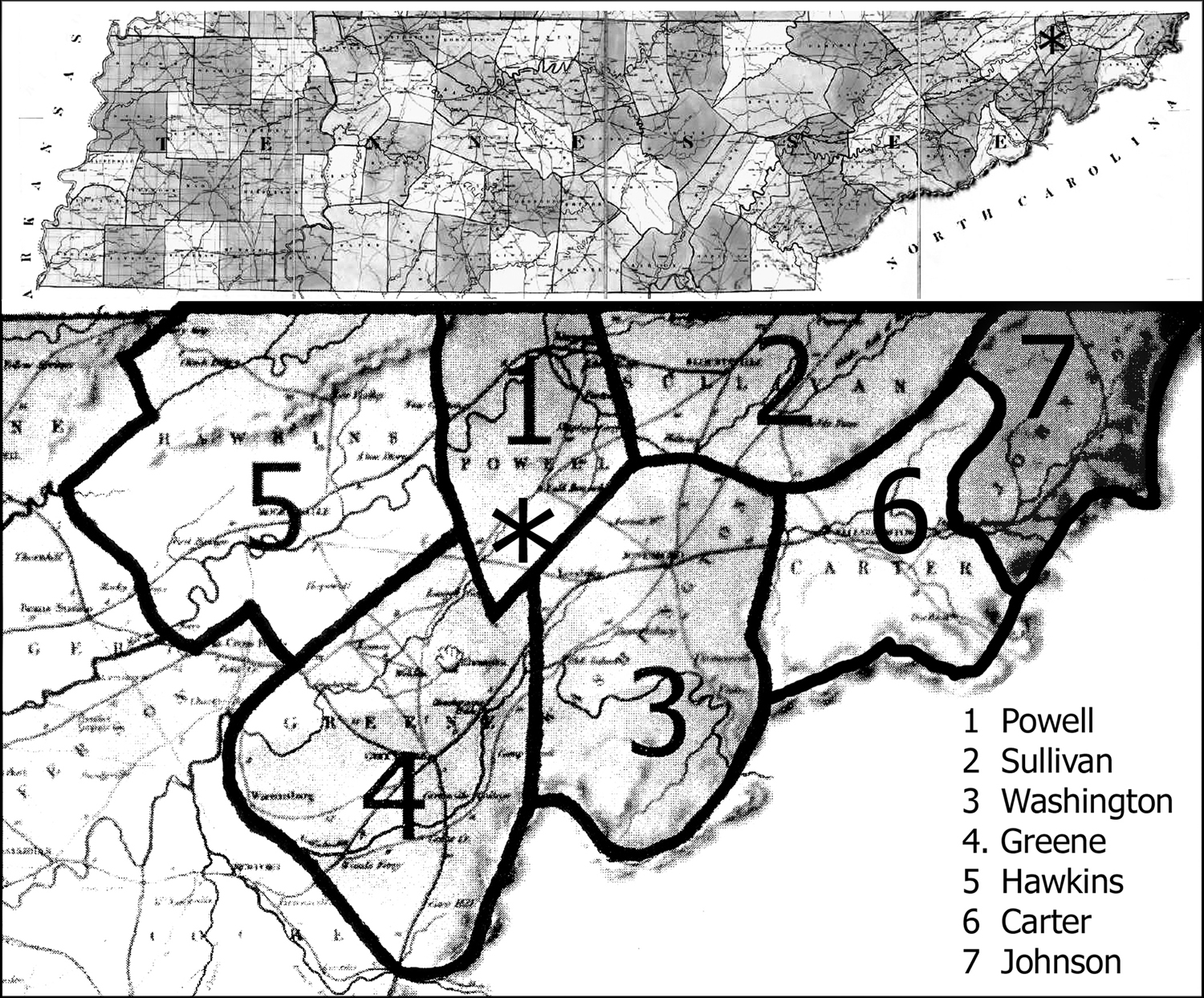

Photo 3

One summer about 1954, area students were invited to show up at Southside School with their favorite dog. The event was a part of the city's Park and Recreation Board's summer program, sponsored by the Jaycees. Jay said that, although he did not own a pet, he was asked to display his soapbox racer to the spectators. Several youngsters brought little cars that had been painted and dressed up with tin cans, reflectors and the like. Jay actually had a hook on the back of his bicycle he used to tow his racer. He likened this to early NASCAR promotions. Jay said the group comprised several grades.

On the front row, left to right, are Claudine Shugart, Becky Taylor, Bobby Lilly, Jack Lawson, Jimmy Shugart, Mike McNeese, David McNeese, Laura Morris and John Miller Bray. On the back row are Martha Jean Crumley, John Jones and Jay Prater (sitting in his car).

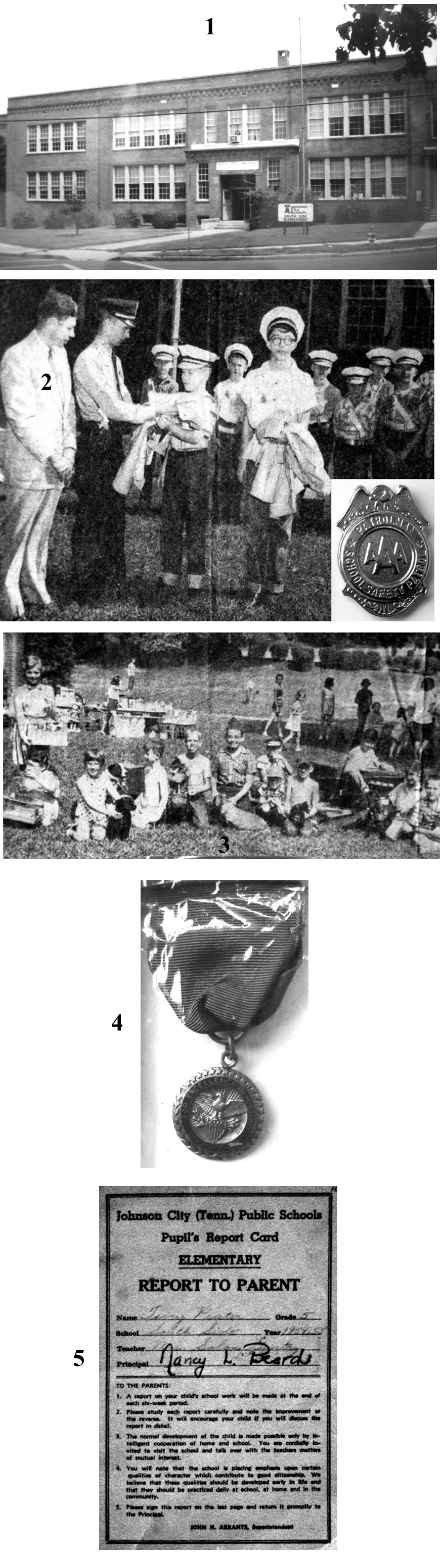

Photo 4

Terry referred to his report card as “the dreaded document” for school year 1954-55, bearing the names of his sixth grade teacher, Mrs. Solon Gentry, and the school's principal, “Nancy L. Beard.” The school superintendent, John H. Arrants, is listed at the bottom. I chided him about not showing both sides of the card.

Photo 5

The school offered awards to students for achievements in a number of areas. Jay received an “Excellence in History” one from the D.A.R. (Daughters of the American Revolution) for his design and construction of a replica of a Civil War Fort. It was about two feet square with watchtowers on each corner and constructed of building materials such as ice cream sticks. Although it was left at the school for future show-and-tell, Jay wondered if it might still be there.

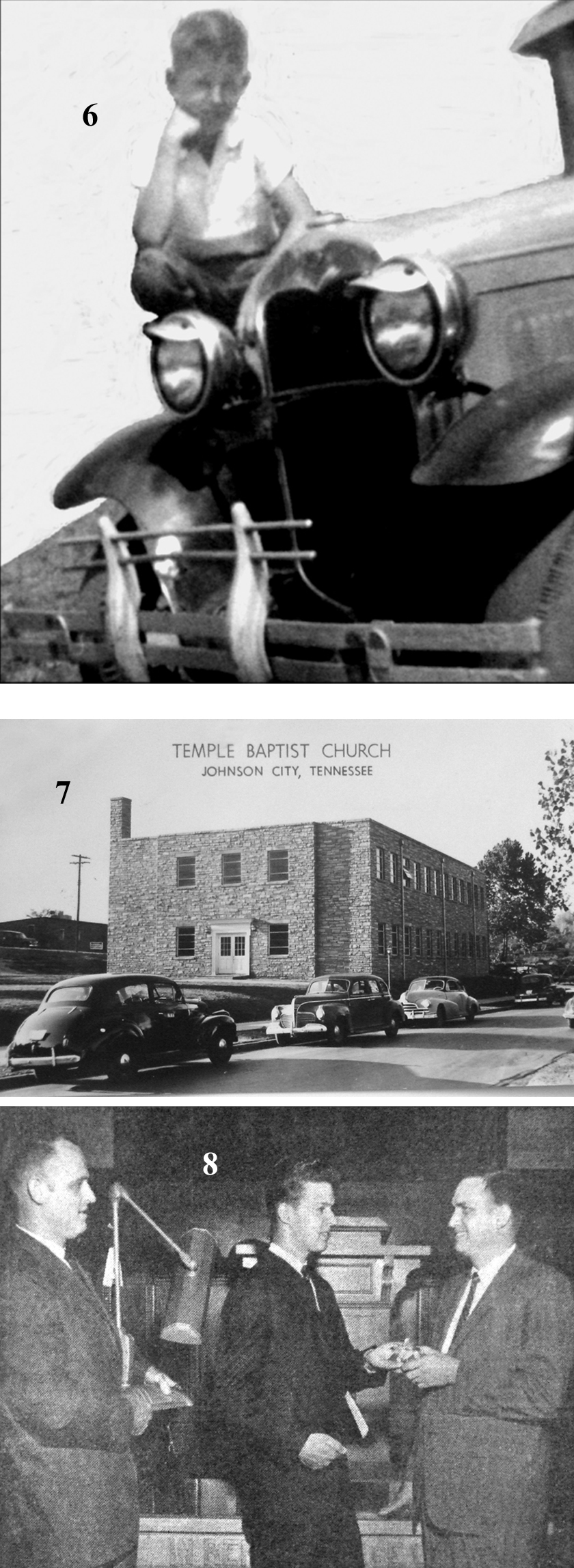

Photo 6

Terry's father purchased a special gift for his son, a beautiful 1930 Ford Model A coupe for $30 that was complete with rumble seat and white wall tires. Prior to his family acquiring it, the car sat on a hill near Kingsport for several years before being “rescued.” The “A” was later sold for $50 in the interest of purchasing a cool Whizzer motorbike.

The coupe was painted maroon with black fenders and polished chrome. This was in the days when gasoline was 19 to 21 cents a gallon and often cheaper. He recalled frequently buying one gallon of gas at a time for it.

Jay related a humorous story: “We had an alley behind our house on W. Maple that ran the entire length of the block. It afforded this Southside hot rodder a place to impress his schoolmates and irritate the homeowners as dust was no small problem then. On one occasion, with the rumble seat full of friends, I turned around at the end of the alley and spotted a police cruiser slowly making its way toward me from the other end. I quickly backed up, found a small parking space nearby and we all ran inside Bill Darden's Rainbow Corner, a safe haven at 337 W. Walnut and Earnest Street.

“Moments later, while my nervous friends and I cowered low in a padded booth, two big officers strolled in the establishment, looked around and moseyed over to where we sat, terrified and hardly breathing. 'Who's driving the Model A?,” asked one of the officers. I confessed and immediately began visualizing what the inside of a prison would be like. With a slight but detectable grin, one policeman said, 'Son, that Model A is creating some dust you know.' That was all he said. I guess the world was not such a bad place in 1953.”

Photo 7

The new building of Temple Baptist Church in 1954 was located at the corner of E. Maple and Division streets. The older and previous church was at the corner of E. Maple and Afton. The car on the left is a shiny and new looking 1940 Chevrolet that belonged to Jay's parents. The pastor at the time was Rev. Joe Strother. Many years later, the new four-lane highway, now I-26, took the property. The church relocated and is now known as University Parkway Baptist.

Photo 8

“The clipping from April 19, 1964,” said Prater, “is a part of my personal treasures and a reminder of special opportunities afforded me in those early years. I continue to enjoy a friendship with my former pastor Richard Ratliff.”