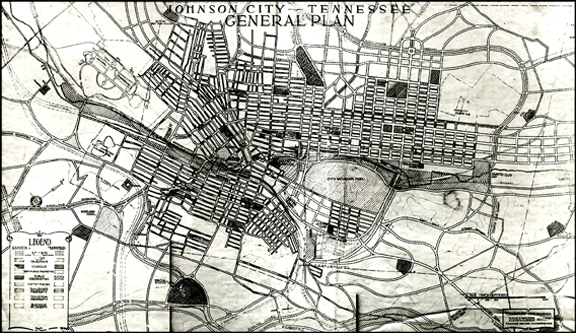

A large 1928 map identified as “Johnson City General Plan” reveals a wealth of information, some of it surprising. The legend identifies symbols for proposed and actual streets, parks and parkways, schools, semi-public properties, public properties, cemeteries, railroad property, industrial property and business property. John Nolan was listed as the city planner.

I immediately spotted something very interesting. I attended West Side School at 304 W. Main at Watauga in the first grade. Printed on the map just west of Peachtree Street across Sidney Avenue (renamed Knob Creek Road) were the words, “Proposed West Side School.” Did the city plan to replace the old one? That did not happen because it was in use until 1961.

The answer lies in the fact that the city needed another grammar school in the rapidly expanding west end of town. City officials apparently had a change of heart and later build it at 812 W. Market (across from Kiwanis Park). Between 1930 and 1934, the Main Street school was known as Old West Side School and the new one became New West Side School. In 1934, the new school’s designation was changed to Henry Johnson School. No school was ever built opposite Peachtree.

Another interesting tidbit was a reference to a “High School Site” on a sizable plot of land sandwiched between Elm Street, Eighth Avenue, Baxter Street and a proposed North Skyline Parkway along the north side. Was this site researched for a new Science Hill (201 S. Roan Street) or Langston (226 E. Myrtle), the city’s black high school? Obviously, no educational facility was ever constructed there.

Other schools displayed on the map were East Tennessee Normal School, Junior High, Martha Wilder, Columbus Powell, Keystone, Douglas (black), Dunbar (black), Piney Grove, Roan Hill, North Side and South Side. Notably absent was New Martha Wilder (renamed Stratton). Another sizeable parcel of land situated south of the intersection of Buffalo and Highland was marked, “Special School Site.” No additional information was offered.

As I further perused the map, I spotted four more anticipated parkways in addition to the aforementioned North Skyline one: Country Club, Cherokee, Woodland and Sinking Creek.

While most of Johnson City’s street identifications in 1928 were identical to those of today, a few changed names over the years. Case-in-point is the group of ten parallel streets running east and west from Tannery Knob toward North Johnson City. Remnants of a failed attempt by wealthy steel magnate Andrew Carnegie to build an imposing new town named Carnegie along the northeast end of the city were visibly evident. The Carnegie avenues (and today’s names) were First (Millard/Railroad), Second (Fairview), Third (Myrtle), Fourth (Watauga), Fifth (Unaka), Sixth (Holston), Seventh (Chilhowie), Eighth, Ninth and Tenth. The names on the 1928 map showed First, Fairview, Myrtle, Watauga, Unaka, Holston, Seventh, Eighth, Ninth and Tenth.

Other observations from the plan revealed a future City Mountain Park on what is now known as Tannery Knob, the main Post Office located on Ashe Street (later became the Ashe Street Courthouse), a Jewish Cemetery adjacent to Oak Hill Cemetery at the intersection of Whitney and Wilson, the VA referred to as National Sanitorium and several planned roads the length of the south end of E. Main. One in particular, Glanzstoff Road, was named for the American Glanzstoff plant in Elizabethton (renamed North American Rayon Corporation). It became the new Johnson City/Elizabethton Highway.

The 1928 city-planning map offers another glimpse of vintage Johnson City and adds additional pieces to the city’s “history mystery” puzzle.