In January, 2010, I wrote an article about the collapse of White Rock Summit on Buffalo Mountain that occurred Jan. 25, 1882. A few newspapers from around the country and one from Mexico began to slowly report the news.

An Old Newspaper Reports the Collapse of White Rock on Buffalo Mountain

Roughly 750 Johnson City residents experienced something that afternoon that left them helpless and reeling with fright. A powerful crash and terrifying rumbling noise that could be heard 30 miles away came from the mountain, caused by a major rockslide that occurred on the southeast terminus of the mountain.

Panic-stricken inhabitants living in close proximity to the mountain fled from their dwellings seeking protection, fearing that an earthquake was besieging the East Tennessee countryside. A number of folks gathered together to pray for deliverance from the falling mountaintop.

White Rock on Buffalo Mountain As It Appears Today

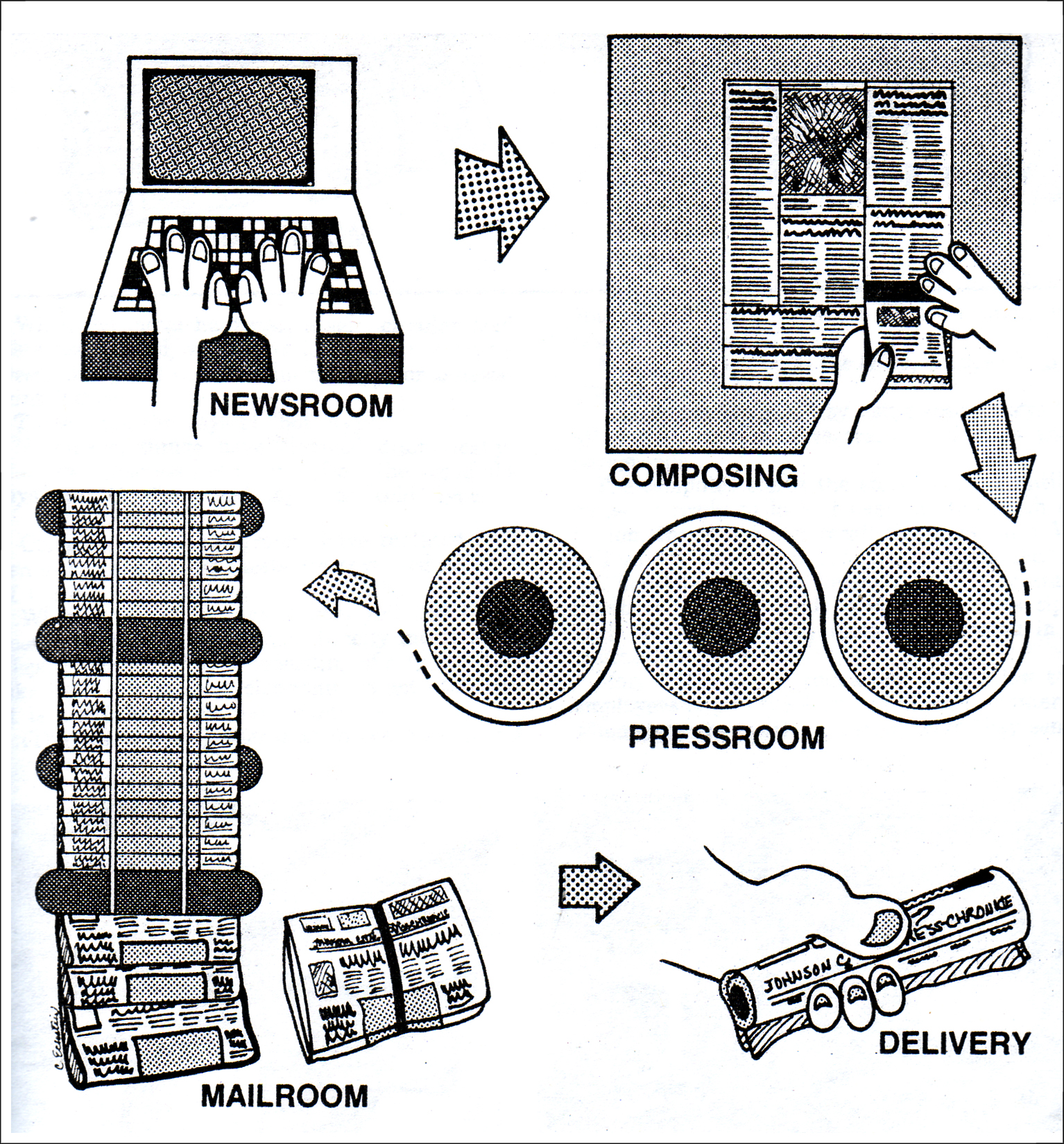

Recently, I located another and more detailed source dealing with the 1882 collapse. The crash occurred at 3 p.m. on that Wednesday. When news reached the Knoxville Chronicle that a section of Buffalo Mountain, located in upper East Tennessee, had crumbled to the valley, a reporter was immediately dispatched to Johnson City, the closest town to the scene of the devastation. Upon arriving, he learned that White Rock Peak (referred to as White Rock Summit in other publications) had succumbed to geological agencies, namely continuous rains, spreading debris over a large mountainous track of country.

Procuring a guide and two good horses, the riders apprehensively began their trek up the mountain. Snow was falling in the valley and as they made their ascent to the peak, the drifts became deeper and deeper. By the time they reached the summit, using a circuitous route, the accumulation was 18 inches.

Prior to the huge structure of quartz crystals falling prey to natural forces, the mass could be seen from afar, appearing as a specter standing guard over the towns and valleys beneath it. The rock was nicknamed “Lone Sentinel” by some residents. It was, by far, the highest peak on Buffalo Mountain.

Amazingly, the end of the mountain which formed the massive rock was about 1500 feet above the surrounding countryside and was almost a perpendicular cliff'. The rest of the mountain, excluding the rock, was covered with a heavy growth of timber, prominent among which was oak and chestnut trees. The brow of the mountain was estimated to be a half mile or more across and composed for the most part of white sandstone.

When the newspaper team arrived at the top of the mountain, they gazed in wonder and astonishment. There in front of them, now partially covered with snow, they witnessed debris strewn for a mile down the mountain side, the result of the stupendous crash.

Rocks as big as houses had been hurled into the valley with a terrible force, uprooting trees and cutting down everything in its path.

The track of the rocks in their terrible downward departure was perceptible for a mile or more. A boulder weighing several tons, which had somehow diverged from its course, was lodged against a single tree, but most of the rocks of all sizes had fallen to occupy the valley below.

Trees several feet in diameter were cut completely in half, some as high up as 40 feet, clearly showing what a powerful force must have urged the rocks to ascend to a lower position. They could but stand in mute admiration of the slow yet steady and powerful forces of nature which had moved the end of the mountain to the mountain ridges to the west.

After the rumble ceased, solid rock composed of white sandstone glittered in the now bright noonday sun, the radiance of whose rays could be seen for miles by onlookers. Because of its white appearance, the rock had acquired its name, which reportedly was on record several places in written history.

The two men conversed with several area persons in regard to the cause of the great fall of rock. Some were of the opinion that the crash was caused by a movement in the earth's crust, like an earthquake. Others were of the convinced that it was the result of what geologists term “aqueous agencies.”

Those residents who wanted to know what happened were vividly aware that since Christmas 1881, the area had undergone a continuous deluge of rain. Water managed to infiltrate the rock in the frigid climate and then freeze, causing it to expand and split the rock, ultimately to a depth of a hundred feet or more. It was generally speculated that this destructive force had been at work causing the big rock to fall into the valley below.

My new source offered an interesting historical note to the property beneath the rock. It was frequently spoken of in history books of Tennessee as the spot where Governor John Sevier and his friends and Colonel John B. Tipton and his allies met in a bloody and fatal scuffle just 94 years prior (1788).

While this portion of the state was still a part of North Carolina, it seceded and set up a state government of its own in 1784, calling itself “Franklin.” Governor Sevier, was elected chief magistrate and commander of the militia. North Carolina, still claiming this territory, appointed her officials, thereby causing a conflict.

Colonel John B. Tipton was chosen County Court Clerk of Washington County. He lived at the foot of White Rock and Governor Sevier, followed by 150 men, proceeded to the house of Tipton to divest him of the official papers. Colonel Tipton, backed by a strong force, routed the Sevier allies. Several men were killed and wounded during the day on account of this engagement.

Although White Rock has often been referred to in the histories of Tennessee with pride, now that it passed through such a transcending ordeal, its name will shine even brighter in the archives of yesteryear.