On June 10, 1984, Scott Pratt, Johnson City Press-Chronicle staff writer, composed an article titled, “The Process Has Changed.” It concerned the 50th anniversary of the newspaper, which began publication on June 12, 1934.”

“If Walter Winchell, H.L. Mencken or William Randolph Hearst were to return from the grave today,” Paul said, “they would no doubt be astounded by the transformation of the journalistic world they once roamed.”

Many of the methods these great “purveyors of prose” applied remain basically unchanged, with editors still assigning reporters to cover events and then writing their impressions of them.

Pratt further noted: “Comparing the mechanics involved in the actual printing of news in 1934 and what took place in 1984 was much like comparing the first Gemini space capsule with the sleek ships of Star Wars fame.” If Scott was writing this article today (2014) instead of 1984, the comparison would be markedly more dramatic.

The Newsroom Where Editors Process News Copy Written By Reporters

At the Johnson City Press-Chronicle in 1934, a news story was ushered into the newsroom by a reporter and typed using a manual typewriter onto a sheet of paper. When he or she finished, the reporter hand carried the story to an editor, who glanced looked it in much the same fashion as an elementary school teacher grades an English paper.

The editor would then mark the type-written story with a pencil, correcting grammar and spelling errors and making sure the reporter had his facts straight. Once the editor had finished, he sent the final draft of the story to the composing room, located on the same floor as the newsroom.

It was here that the news story followed a cumbersome process from paper to hot lead via a Linotype machine. This device, now a dinosaur of the printing business, fashioned a solid line of printing type (hence the name, “linotype”) on “slugs” of lead. It became standard operating equipment in the newspaper business for nearly a century, spitting out type at the “lightening-fast” rate of four lines per minute.

Once the story had been cast in lead, it was laid out on a rolling cart with a framed metal table top, appropriately dubbed a “turtle” because of its cumbersome size and awkwardness. The frame on top of the turtle was the size of a newspaper page and it was into this frame that the lead slugs were fitted to form the rough draft of the page.

By the time the pages were fitted, they weighed 30-40 pounds. The lead pages were then rolled via the turtle to a device called a mat press, where a thick fiber mat was laid over the page and compressed by a large roller. By this time, the story had gone from paper to lead to fiber mat, but the process was not yet finished.

The story had to return to hot lead. The mat, now transformed into a “dummy” or page model, was placed on a cylindrical mold called a plate marker. It was here that the molten lead was poured on the dummy.

When the metal hardened, a semi-circular lead plate was formed, which was locked onto a rotary press, inked and used to convert the page onto newspaper print. Those were the days of “hot” type. Computers and photography replaced molten metal and plastic sheets were used in place of the old lead plates.

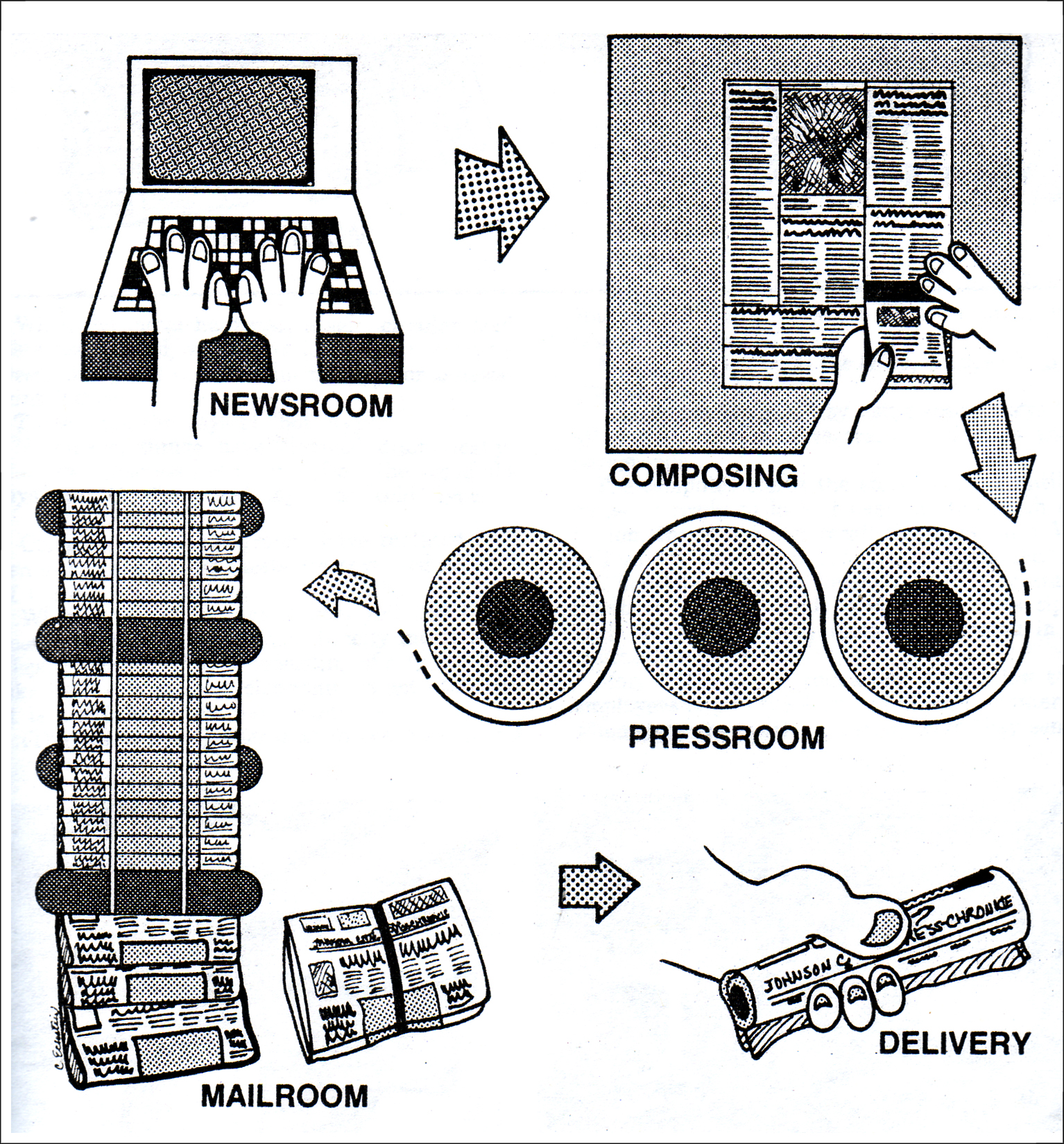

A Simplified Sketch from 1984 of the Newspaper Process From Newsroom to Delivery

When a reporter brought a story into the newsroom in 1984, he or she typed directly into a video display terminal (VDT), consisting of a typewriter-like keyboard with an electronic screen attached. It was a link with the main computer. Typewriters began to gather dust and were only used to write letters, memos or in case of an emergency.

As the reporter typed the story, it appears on the screen. Corrections are made by using special keys that allowed the reporter to rearrange sentences and paragraphs.

The computer placed the story in a file until an editor was ready to review it. At the touch of a button, the editor could recall the story on a VDT and examine it while it was still in the computer.

When the editor was finished, he or she simply inputted a few commands and the story was zipped back into the composing room to be stored in yet another computer file. More VDTs in the composing room allowed the employees there to pull the story out of the computer file when they were ready and from there it was sent it through a computerized, digital Linotype.

The Star Wars version of the Linotype produced print on photographic paper, complete with spaces and hyphens. Rather than the four lines per minute of the hot lead Linotype, the new one was capable of 450 lines per minute, a dramatic improvement.

Once the story had been proofread, it was pasted on a paper sheet according to a layout showing where the stories and pictures should appear in the paper.

The layout, somewhat like a map of the page, was drawn by a news editor and sent back to the composing room via a vacuum tube in the ceiling.

The pasted-up page, when completed and approved by the editors, was photographed and a negative of the entire page was produced.

The negative was placed on a sheet of paper coated with liquid plastic and exposed to a bright light. The light passed through the transparent parts of the negative and hardened the liquid plastic. The other parts of the negative blocked the light and the coating under them remained soft.

The soft plastic was removed from the sheet, leaving the hardened images, which then went through an etching process to raise the hardened areas. The plates were then mounted on the press and the press went into action. O-tone rolls of paper were mounted on the press and drawn through, receiving the print of all the plates. The press also cut the sheets and folded them into pages.

The 3-story printing press at the Johnson City Press was capable of printing a 96-page paper. Larger editions were printed in separate press runs. The papers were then transported on conveyor belts into the mailroom where they were bundled for distribution or addressed for mailing. The bundles were placed on the loading dock where they were gathered, loaded on trucks or in cars and hauled away to newsstands or distribution centers and dispersed to contract carriers who delivered the paper to a box or a rosebush.

Pratt noted that the life of the news story changed dramatically during the past 50 years and many of the changes also affected the lives of people who devotedly read the news. Tremendous technological gains in the news media time and again proved that insurmountable challenges could be met through ingenuity and resourcefulness.

The old adage “They just don't make 'em like they used to” definitely applies to ongoing technology improvements in the newspaper business.

Comments are closed.