According to the Johnson City Press-Chronicle, “Kermit Tipton, who last night was elevated from Junior High School coach to the head coaching post at Science Hill School, is a graduate of Milligan College and gained his Master’s Degree at the University of Mississippi.

Tipton, whose football and basketball teams and later Junior High, posted successful records, succeeded Jack Green as head grid mentor of the Hilltoppers.ö

Smallwood Direction

“Sidney Smallwood, basketball coach, was recently named overall athletic director of the city athletic program. The 34-year old Tipton, a former Science Hill football great, starring as a Topper, from 1938 through 1940. Tipton then attended Milligan in 1941 and 1942, before entering the United States Army, where he served in the Infantry for three years. In 1953, he received his Master’s Degree at Ole Mississippi.ö

Coached At Lamar

“Tipton was assistant coach at Lamar in 1949 and 1950, but moved up to the head coaching job at the Washington County School in 1951. In 1951, Tipton’s football won five and lost two. His basketball won 20 and lost five.

“In 1952 at Lamar, the Cherokees under Tipton won five and dropped three in football and won 19 and lost eight in basketball.

“Tipton has been at Junior High three years. In 1953, his football team won three and lost three. In 1954, the team won seven, lost one and tied one, and last season the Junior High eleven posted 11 victories against two defeats.ö

Recommendation

“In recommending Tipton for the post as head football coach at Science Hill, Forrest Morris, chairman of the recommending athletic committee, wrote Chairman Ray Humphreys of the Board of Education:

Dear Mr. Humphreys: “We are as requested, present to this board the name of Jack Green, who recently resigned as head coach at Science Hill High School, who in our opinion is capable and will satisfactorily fill this position.

“This young man is a keen student of the game of football and is well known for his ability to teach his boys to play smart, aggressive football. He is very popular with the boys, as he is with all of his fellow coaches.ö

“Likewise, he is respected and held in the highest esteem by his competitors, as well as the fame officials. To all familiar with the game of football, he is recognized as one fully capable of fielding smart teams always imbued with a desire to win.

“He is a poor loser, in the sense that he always plays to win and hates to lose, yet he is not one who would at anytime sacrifice the basic ideals of good sportsmanship and clean fair play just in order to win.

“To him, such would be impossible since good sportsmanship and clean fair play is much a part of his of his everyday living, on or off the gridiron. Truly, he is the type of young man with whom we would be willing to trust our own sons.

Kermit’s Success

“Kermit has been successful in his present position, and in the opinion of this committee, has done an all-round good job, therefore it is more or less in the spirit of a “reward for a good job well done” that we present the name of Kermit Tipton, the present head coach at Junior High and recommend that he be elevated to the Science Hill High School position.

Respectfully submitted, F.K. Morris, chairman, Athletic Committee Member.

And The Rest Is History

“The name of Kermit Tipton went down in Science Hill High School football history never to be forgotten.ö

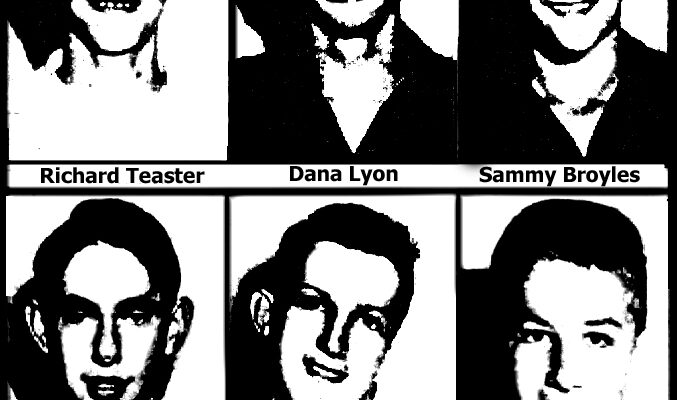

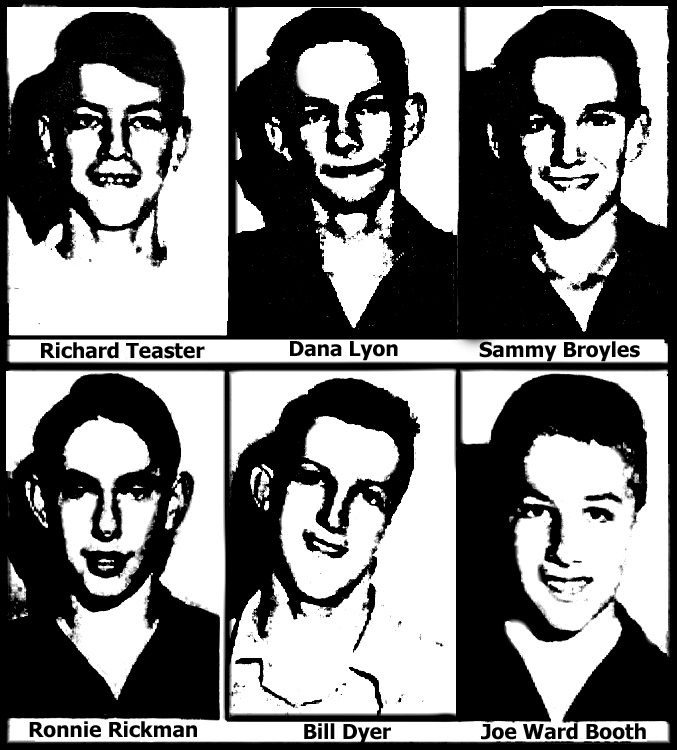

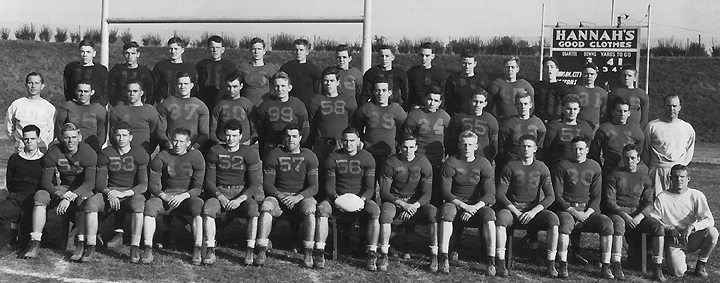

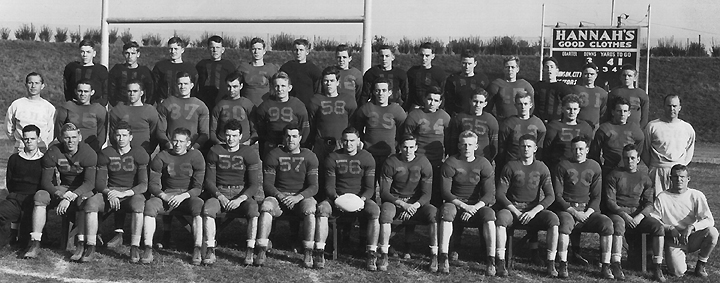

Photo Accompanying This Column

“The photo with my column is from December 5, 1957. The caption reads, ‘Most Outstanding ‘Topper – Jule Crocker, center, Johnson City Hilltopper guard, holds his most outstanding trophy, awarded him by the Johnson City Junior Chamber of Commerce. Left to right is ‘Topper coach, Kermit Tipton, Lynn Cooter, and Jule Crocker. It was put in the school’s trophy case.ö

Writing this article evoked such pleasant memories for me from that era of sports history.

_0-1050x400.jpg)

_0.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)