The completion of the Carolina, Clinchfield & Ohio (CC&O) Railroad from Dante, Virginia to Spartanburg, South Carolina occurred on Friday, October 29, 1909. Festive celebrations were observed in Johnson City and Spartanburg.

The excitement was the fulfillment of a new railroad that would transport coal from a rich coalfield. It was built at an enormous cost brought about by engineering challenges associated with the rough terrain. The CC&O became known as “one of the greatest little railroads in the United States.”

The Virginian railroad that was built under similar difficulties and with a comparable stated purpose was the pet project of H. H. Rogers. The new line was the favorite enterprise of Thomas Fortune Ryan. The road was built over and through the Blue Ridge Mountains, rising from 1,500 feet to more than 3,000 feet above sea level within a few miles and still maintaining a maximum grade of one-half of one per cent. A single engine could pull a train of 60 heavily loaded freight cars across a rarely seen beautiful mountain region.

Numerous tunnels were built, including two that were almost a mile each in length; one of them cost $500,000. Across a difficult stretch of many miles in the mountains, the road cost totaled as much as $200,000 a mile.

When the economic panic came along two years prior to completion, work was suspended almost everywhere with two exceptions – the CC&O Railroad and the Panama Canal. Uncle Sam continued to dig the canal while Mr. Carter methodically drilled through a great chain of tunnels, which included 17 within a distance of 18 miles. A low grade was arbitrarily maintained regardless of cost. Occasionally, money was wasted when afterward if was determined that the work did not achieve the required grade. That section of track was abruptly abandoned.

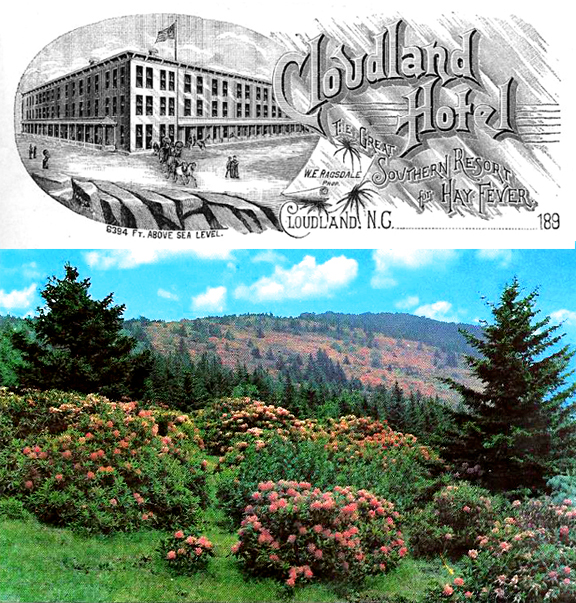

Not far from the CC&O road was George W. Vanderbilt’s immense Biltmore estate built at the unheard of cost of $1,000,000. It was said that the altitude of the region was the greatest in the East and the scenery was unsurpassed anywhere in the world. Ultimately the new railroad became a link in a trunk line from the Great Lakes to the south Atlantic seaboard.

The Johnson City celebration, one of the most elaborate gatherings in the City's history, took place at Hotel Carnegie on E. Fairview with the presidents of Johnson City's three railroads attending. Congressman Walter P. Brownlow served as master of ceremonies with speeches, toasts, a banquet meal and fine cigars smoked long into the night. The city’s most prominent business leaders attended as well as one special guest, General John T. Wilder, who started the great railroad but failed to complete it. He fittingly was honored and then given the floor for a speech.

In Spartanburg, thousands of people attended the event with over 1,500 persons treated to a barbecue celebrating the first train to arrive on the CC&O Railway.

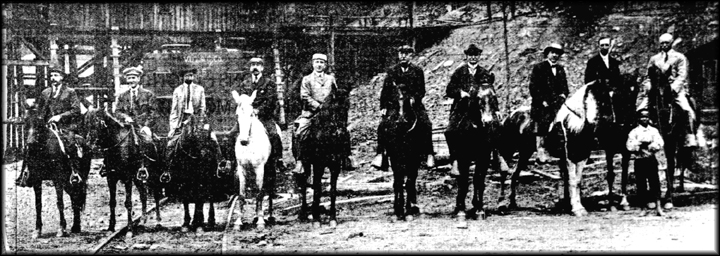

My column photo shows Thomas F. Ryan and a party of associates in the mountains, not far from Bristol, Tennessee, preparing for a ride through the wilderness along the route of the new railroad.

Left to right are George L. Carter (president, CC&O Railway), Isaac T. Mann (mineral operator, owner of many Southern banks), George A. Kent (former chief engineer, CC&O), John B. Dennis (Blair & Co.), W. M. Ritter (one of the wealthiest operating lumbermen in the country), Norman B. Ream (director in many American railways, trust concerns and insurance companies), Thomas F. Ryan, James A. Blair (senior member of Blair & Co.), H. R. Dennis (Blair & Co.) and James Hammill (chief counsel for W. M. Ritter interests).

-504x400.jpg)