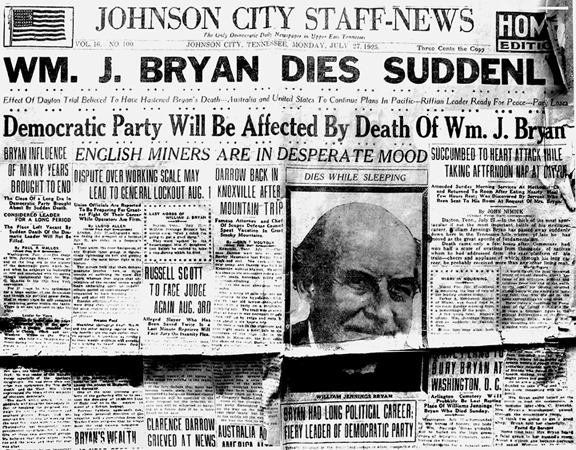

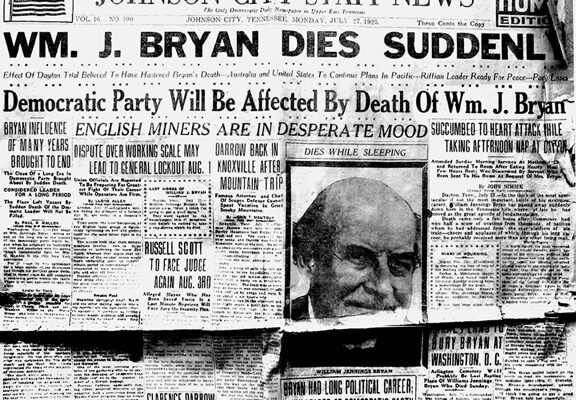

The bold headline of the July 27, 1925 Johnson City Staff-News proclaimed, “WM. J. Bryan Dies Suddenly.” The noted politician died the previous day in Dayton, Tennessee. He visited Johnson City on at least one occasion, lodging at the Windsor Hotel on Main Street. Within three days, Bryan’s body would make a final passage through East Tennessee by train en route to his final resting place at Arlington National Cemetery.

Mr. Bryan, a dominant force in the Democratic Party, made three unsuccessful bids for President. He supported prohibition and opposed Darwinism for religious reasons. “The Great Commoner,” so named because of his faith in common people, became a sought-after public speaker.

The commoner is best known for his principal role on the prosecution team at the 1925 John Scopes Monkey Trial in Dayton, Tennessee. Scopes, accused of teaching evolution in a public school, chose Clarence Darrow for his defense lawyer. Although, the jury convicted Scopes of the charge, an appeal’s court later overturned the verdict on a technicality.

Just five days after the trial, the self-confident lawyer died in his sleep after a heavy meal. Some felt the trial significantly contributed to his death. On July 30 at 8:50 a.m., two special railcars began transporting Bryan’s remains accompanied by his family on a 24-hour journey to the Nation’s Capital. Along the way, thousands of persons besieged the train as a show of respect to the fallen leader.

Although the train was only scheduled to stop at Chattanooga, Mrs. Bryan ordered another one at Knoxville when she learned of the massive crowd that had assembled there. As the train journeyed by Jefferson City and Johnson City, women at the depots sang hymns that included “One Sweetly Solemn Thought” and “How Firm a Foundation.” The train passed through Bristol at 11 p.m. In every town and hamlet, flags were flown at half-mast and many churches sent floral offerings to train depots to show their respect.

The funeral entourage arrived at Union Station in DC at 7:40 a.m. on July 30 where approximately 1,000 people were waiting in the vast concourse. A significant dispatch of police officers stood by and a horse mounted squadron kept the exit clear for the movement of the casket.

Bryan’s widow left the funeral car before her husband’s body was removed. She was escorted to the rear platform in a wheelchair, which was then raised to the main level of the station in an elevator and taken to her hotel. The strain of the circumstances clearly showed in her countenance.

The gathering in the concourse grew steadily in number. Barricade ropes were put in place as people edged forward to view the casket as it rolled on a small truck through the pavilion. Government clerks hustling to their work desks paused long enough to bow their heads or lift their hats while it passed.

After a brief time at the funeral parlor, the body was taken to the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, where presidents and dignitaries of state had worshipped. Mrs. Bryan chose not to view her husband in public but agreed to a private one just before the body was taken to Arlington Cemetery for burial.

Eight honorary pallbearers who had been selected by Mrs. Bryan included Tennessee’s Senator McKellar, a Democrat. An informal reception committee met the funeral party, representing the State Department, which Bryan headed for two years.

A small delegation of troops from Fort Meyers met the casket at the entrance to the cemetery and escorted it to the gravesite. Mrs. Bryan insisted that the only display of military pomp at the funeral be the playing of taps.

The country had fittingly honored one of its fallen heroes. Mrs. Bryan joined her husband in death in early January 1930.

Comments are closed.