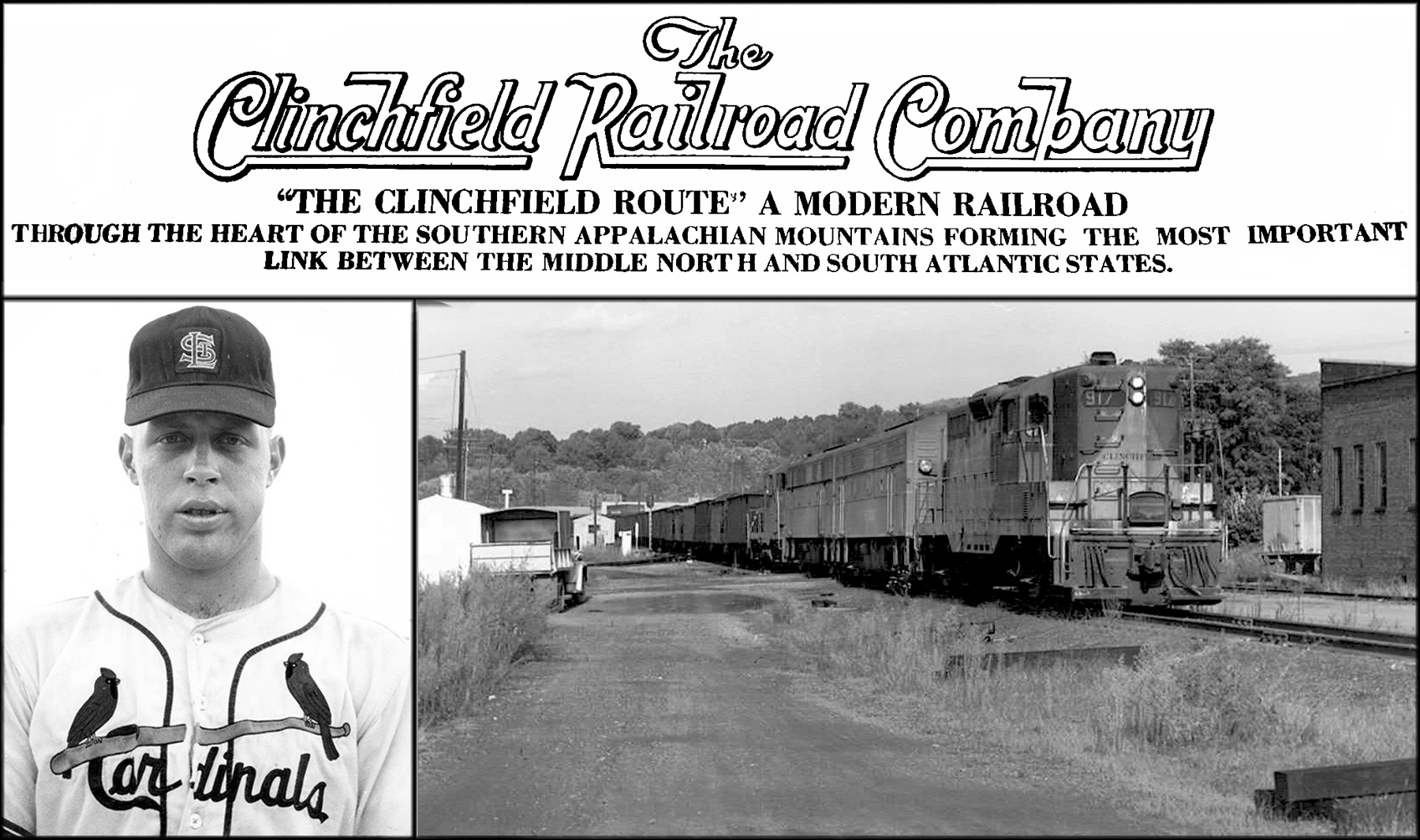

Charlie Morris, a 1961 SHHS graduate spent 40 years on the Clinchfield Railroad (CRR), knowing from his first day on the job that it would be his life-long career.

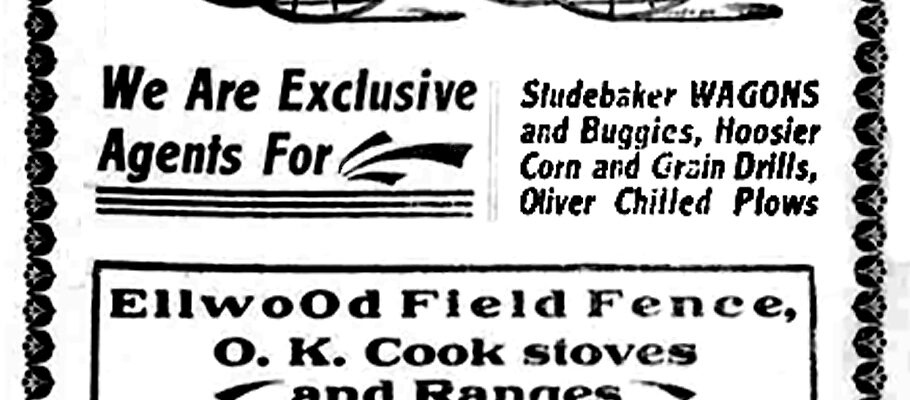

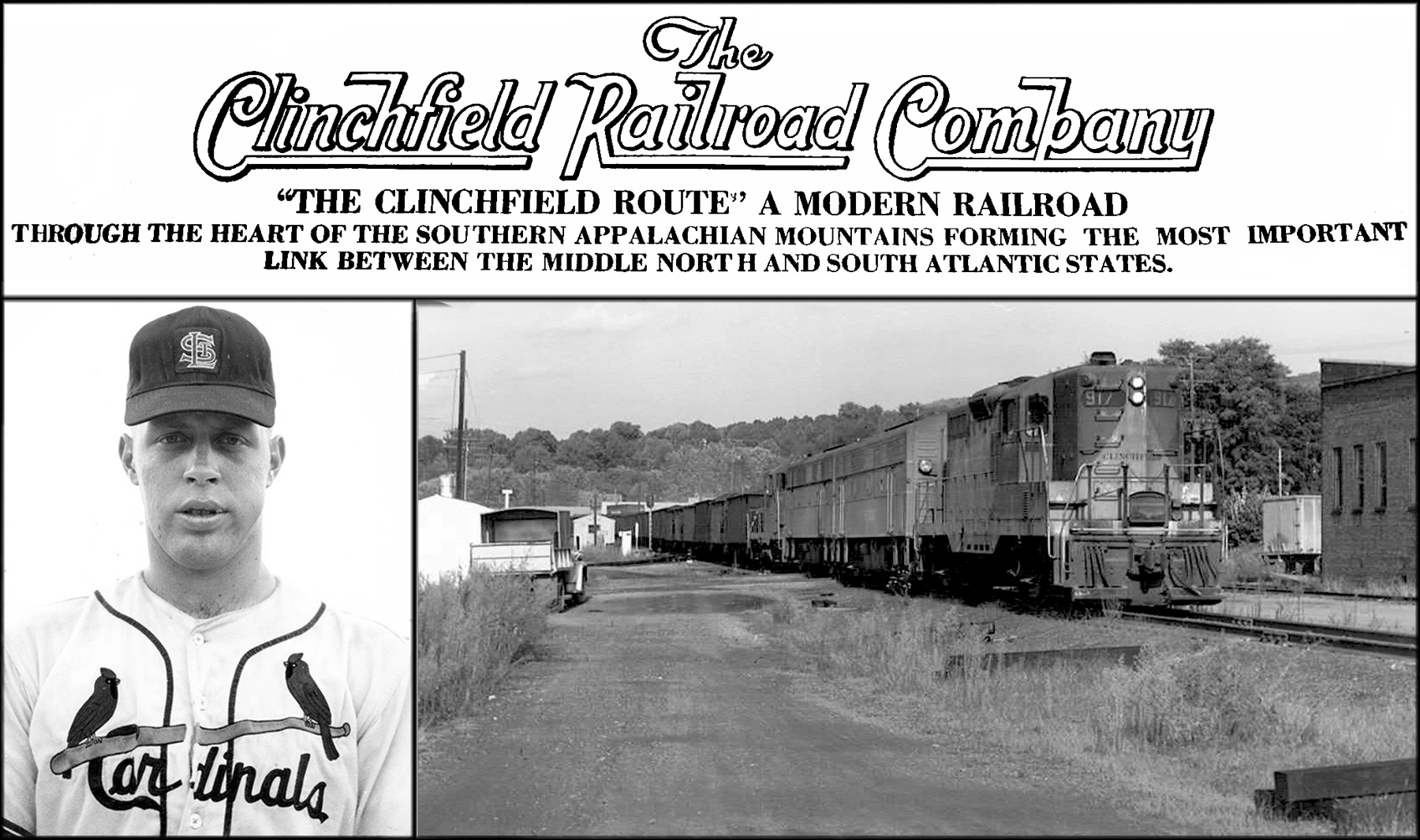

After graduation, the baseball standout went to work at the Jewel Box on E. Main Street. One day, he was approached by a baseball scout suggesting that he try out for the big league. He did so and ended up playing two and a half years with the St. Louis Cardinals. Then, after serving a stint in the Marine Corps, he returned to Johnson City to seek a job.

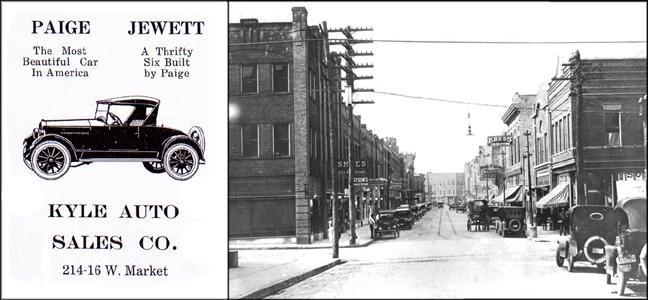

Newspaper Advertisement for the Clinchfield Route, 1930. Charlie Morris When He Played for the St. Louis Cardinals, Charlie Coming into Erwin Yard on Engine 917, 1976.

In July 1964, Charlie was offered employment with the Clinchfield Railroad in Erwin, Tennessee, thanks to the efforts of his uncle, Roy Morris, who worked there; Paul Britt, train master; and D.C. Peterson, railroad detective.

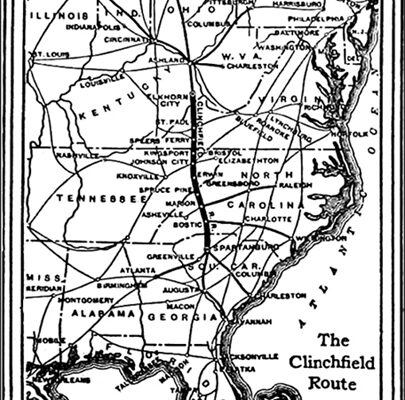

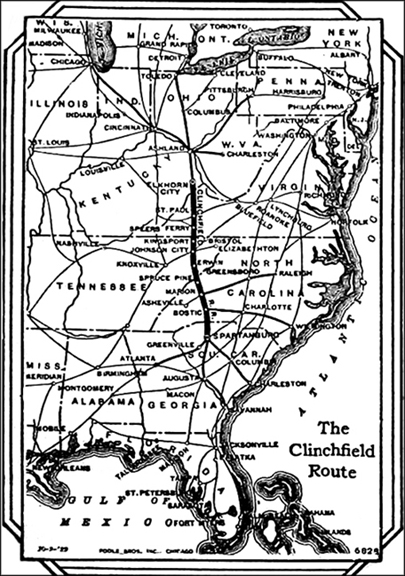

The Carolina, Clinchfield, and Ohio (CC&O) Railway was a merger of unfinished railroads acquired by George L. Carter. Over the years, it would be known as the Clinchfield Railroad, the Seaboard Coastline Railroad and the CSX.

The late 1940s ushered in a new era of diesel locomotives. Gone were the nostalgic steam-driven vehicles. The few existing ones on the yards sat idle until they were either sold to amusement parks or discarded for scrap metal.

Charlie recalled: “When I initially reported to work, six of us were scheduled to train as brakemen. We were assigned to make six trips to the south end of the old Clinchfield Railroad and six trips to the north side.

“The trip north from Erwin to Elkhorn City was known as the 'business' end of the line while the one south from Erwin to Spartanburg was the 'scenic' one. It's hard to describe in words the beauty of the southern end. The north side was in the heart of coal country where we hauled 14,500 tons of coal per train, with 3-15 trainloads per day. Those deliveries increased substantially over time.

“Erwin is 100 miles from Dante, 136 miles from Elkhorn City and 144 miles from Spartanburg. The train speed ranged from about 20-44 mph, depending on traffic, weather and other factors. In those days, we were allowed to work 16 hours, which was considered a full day.

“In the course of our training, the six of us proceeded to make our assigned six trips each, north and south. They presented us with numerous situations and graded us on our understanding of all aspects of the job.”

Charlie explained that a train crew consisted of five positions: engineer, conductor, head brakeman, fireman and flagman. The yard brakeman's duties were different from the road brakeman. The yard brakemen worked the yards around Erwin, Johnson City and Kingsport while the train brakemen rode the trains and worked the roads over which they traveled.

On November 15, 1964, the former Marine received his orders to climb aboard a locomotive engine. He had made the grade, figuratively and literally. At exactly 12:01 p.m., he made his first trip on the railroad for which he drew pay. After that, he worked all over the road, especially at Dante, Virginia where manpower requirements were especially heavy. Although the home terminal was Erwin, the crew worked all over the line in both directions.

“We hauled mainly coal and mixed freight,” said Morris. “Cars were weighed at Dante. The train pulled from about 144 to 220 cars, usually dropping off from 50 to 60 of them at Kingsport.”

One of the rotating duties of working for the railroad was being on-call for 24 hours, seven days a week. That meant staying close at home so as to, within one hour, quickly assemble in the Diesel Shop for any railroad call-in need. Although they had radios back then, they were heavy, cumbersome and uncomfortable to carry on your shoulder.

After Morris had worked about 18 months, running constantly between Dante and Erwin, he was reassigned primarily at Erwin and stayed there until about the middle of 1966. Since the majority of the employees had been on the railroad for some time, they were eager to assist the new recruits in learning the ropes.

By 1968, technology had advanced to the point that Clinchfield acquired several more powerful engines than the existing ones. With time and increasing exposure to the job, Morris became like a sponge, absorbing all facets of the jobs.

Each July, there was a two-week vacation for coal miners that caused a corresponding trickle effect back to the railroad. This caused a temporary reduction of seniority among its employees.

“The brakeman would issue the orders for the day,” related Charlie, “such as Erwin to Dante or Erwin to Elkhorn City. We had a number of places where we set off cars (meaning to park them, empty or full, onto a sidetrack). We would also pick up cars (meaning to remove them from a side track and attach them to the train).

“The old main line ran right through Johnson City. We had a speed restriction of 10 miles per hour in that vicinity. We would usually set-off at Harris Manufacturing Co. The yard was directly behind the old Johnson City Foundry. Sometimes we would set-off just off Greenwood Drive.

“The set-off and pickup stops were specified on our daily list,” said Charlie. “The company tried to schedule all of them in one location, which took a significant amount of planning. The conductor went over the list with the rest of the crew. Although the engineer had total responsibility for the operation of the train, the conductor was the senior man onboard.”

Although there were no passenger trains running by the time Charlie went to work there, Clinchfield made an occasional roundtrip special excursion for customers from Erwin to Elkhorn City in one day. They also scheduled trips to Marion, NC or Spartanburg. This occurred about 1975 on weekends; the designated train became known as the “One Spot.”

Sidetracks were also used to permit one train to wait while another unit passed it. It operated on a signal system with a dispatch in Erwin, having the all-important job of controlling both ends of the railroad. Locations included Hannum, Johnson City, Boone, Fordtown, Kingsport, Kermit, Starnes, Millyard, Moody, Dante, Tramel, Allen, Dinleo, Powers and Elkhorn.

Train problems were generally caused by external circumstances such as derailments, rockslides and broken rails. In 1969, two trains collided causing two fatalities. Charlie said that was the worst thing that happened while he was with the railroad. “My biggest fear while driving a train,” he said, “was hitting a loaded school bus. My second one was colliding with a gasoline truck.

“When a car occasionally stalled on the track, every attempt was made to relay the specific location to the engineer to allow him sufficient time to stop his vehicle. There are several emergency brakes on a train, thereby allowing other crew members to use them when necessary.”

Charlie said that some drivers foolishly think they can outrun a train. He said he once hit a Cutlass Supreme with a glass top whose driver was trying to beat the train, trapping two passengers inside. Morris and others carefully removed the broken glass to free them from the vehicle. They were injured, although not severely. An old railroad saying proclaims that there is no such thing as a tie in a race between a train and a car.

Hobos frequently hopped onto trains. Many of them were crafty, having advanced knowledge of where each train was heading and which cars were the easiest to ride. They jumped on coal cars, empty hopper cars, boxcars and even on top of the braking equipment.

The former pro baseball player vividly recalls Aug. 25, 1984 as his last run of the Clinchfield Railroad with issued orders. The train left for Spartanburg that day as the Clinchfield Railroad and returned that same night as the Seaboard Coastline Railroad. He still has the orders as a souvenir of that memorable trip.

Engine 821, a “Covered Wagon” Style Locomotive with Rare Dual Headlights. Morris (shown on the right) on the 60th and Last Santa Claus Train, 2004.

Charlie was passionate about one aspect of his railroad career: “I had the pleasure nine times of being the engineer on the Chamber of Commerce sponsored Santa Claus train for area youngsters. It ran between 1944 and 2004. I was fortunate to make its last run.

“The train cranked up in Erwin and made a total of 18 stops for eagerly waiting youngsters. We distributed 15 tons of candy and toys. The crowd ranged from a sizable number to perhaps a dozen or so. The train ended its run in Kingsport with Santa getting off the vehicle and being escorted onto a float for the downtown Christmas parade there. Country music singer, Patty Loveless, participated in several of the events.”

Charlie gave honorable mention to several of his co-workers: Bud Chapman, John Kelly, Red Chaffin, George Osborne, Spud Chaffin, Doc Heffner, Sylvester Leonard, Sherman Leonard, Sonny Brotherton, Hubert Leonard, Phil Laws and Windy Whittimore.

Charlie concluded by saying: “I thoroughly enjoyed my career as locomotive train man, conductor and engineer. Although it was a constant challenge handling these trains, I loved every minute of it. I had a great career and worked with some fantastic people.”