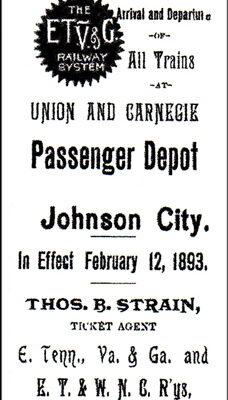

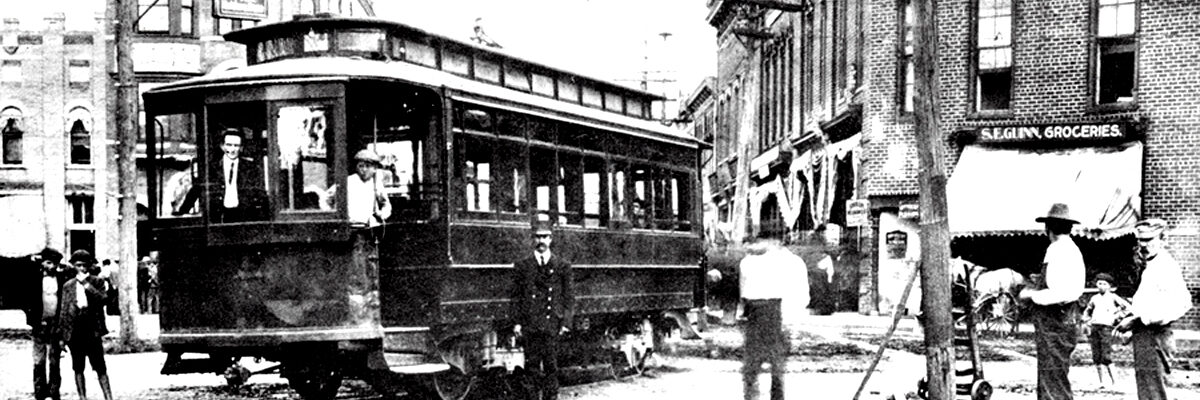

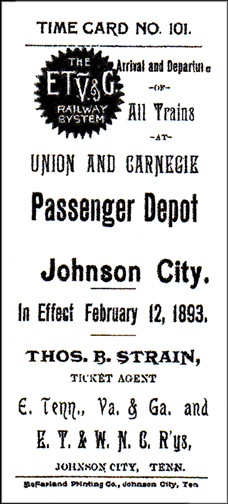

I received a copy of a time card for trains and trolleys at the Union and Carnegie Passenger Depot for February 12, 1893. It consisted of a long narrow sheet of paper, folded six times for ease of use and printed on all sides containing 23 local advertisements and nine railway systems:

East Tennessee Virginia and Georgia, Tennessee and Ohio, North Carolina Branch, Knoxville and Ohio, Embreeville Branch, Johnson City and Carnegie Street Railway (streetcar), Walden’s Ridge Railroad, CC&C and East Tennessee and Western North Carolina

A glance over the ads reveals a nostalgic look back to a simpler Johnson City.

Hotel Carnegie: “The Only First-Class Hotel in the City. New Elegant and Attractive. $2.50 and $3.00 per day. Special Terms to Commercial Men. Electric Cars to and from Hotel Every 20 Minutes. R.W. Farr, Proprietor.”

C.F. Melcher: “For Furniture, Carpets, Oil Cloths, Mattings, Shades and House Furnishing Goods of Every Description. Prices Guaranteed to be the Lowest.”

The Iron Belt Land Company: “Will Harr, President. C.G. Chandler, V. Pres. F.P. Burch, Attorney. W.A. Hite, General Agent.”

Webb Brothers: “Dealers in Fresh Meats, Chickens, Butter, Eggs, Etc. Fruits and Vegetables in Season. Ocean, Lake and Gulf Fish.”

F.M. George & Co.: “Dealers in Lump and Steam, Wood, Lime and Cement. Office on Spring Street. Prompt Delivery.

W.L. Taylor & Bros.: Wholesale and Retail Dealers in Feed, Groceries, Glass, China, Queens and Tinware.”

Seaver & Summers: “Oldest Hardware Firm in the City. Paints and Oils, Sash, Doors, Etc. Agricultural Implements.”

Hotel Greenwood: “Centrally Located. Rates: $1 Per Day. W.M. Patton, Proprietor.”

W. A. Kite & Co.: “Real Estate Dealers and Agents.”

I.N. Beckner: “Dealer in Watches, Clocks, and Jewelry. Silver and Silver Plated Ware. Spectacles, Sewing Machines, Etc.”

W.W. Kirkpatrick: “Leading Clothiers and Gents Furnisher.”

R.G. Johnson: “Furniture, Carpets, Oil Clothes, Mattings, Windows, Shades and Draperies.”

McFarland & Co., City Drug Store: “Prescription Druggists.”

T. B. Hurst & Co.: “The Tireless Toilers for Trade. The Most Complete Dry Goods and Millinery Store in East Tennessee. Wedding Trousseaux a specialty.”

Gump Bros.: “Clothing and Gents’ Furnishings. Opera House Block.”

P.F. Wofford: “Harr-Burrow Block. Druggist.Carries the Largest Line of Drugs, Toilet Articles and Cigars in the City.”

The Bee Hive: “Headquarters for Drugs, Tobaccos, Candies, Fresh Meats and Groceries.”

A.P. Henderson & Co.: “Dealers in Staves, Tinware, and Galvanized Iron Cornice. Roofing and Guttering a Specialty.”

Palace Livery Stable: “Englesing & Snapp Proprietors. Elegant Turnouts for All Purposes. Special Rates to Drummers (traveling sales reps).”

D.K. Lide: “Hardware, Cutlery, Paints, Oils, Glass, Sash, Doors, Blinds, Grates, Water Elevators, Pumps, Etc. Railway and Mining Supplies. Dynamite, Fuse and Exploders. Picks, Shovels, Etc.”

First National Bank: “Resources $250,000. Oldest, Largest and Strongest Bank in the County.”

John W. Boring: “Undertaker and Embalmer. All Kinds of Coffins, Caskets, and Metallic Cases Kept in Stock. Telegrams and Night Calls Promptly Attended to.”

The station stops for the nine railway systems will be noted in my next column.