In 1870, an unidentified writer, whom I will refer to as Mr. John Doe, described a train trip he took to Clinch Mountain. The range was about 25 miles south of the Cumberland River and ran nearly parallel with it for many miles, with several breaks and name changes.

John deemed East Tennessee as the “Switzerland of America.” Although it did not have such lofty mountains as those in the Alps, it displayed many stunning mountain ranges with corresponding deep valleys.

In some places, the flatland pulled away from the ridges, leaving a few miles width of valley in which could be found reasonable elbowroom. But soon, the mountain ridges huddled again without any semblance of order, tossed in indiscriminately, dropping off abruptly, abutting one against the other and having various gorges in between.

Around these slender gorges, the road became a creek bed, washing anything that got in its way as it meandered through the mountains in a relentless search for passageway. Doe described a thunderstorm as something sublime, a thing to enjoy, barring the little discomfort of being exposed to it and doubtless getting wet. The lightning hurled its furious bolt down the mountainside over the head of anyone present with thunder tagging along behind it. It crashed with echoing volleys through the passages, producing an appallingly grandeur about it.

According to the writer: “I had the delight of witnessing a storm that was unique and beautiful; it seemed to burst out from the bosom of a cloud as if in a rage. Angry at being so confined, it shot off eastward, hastening along the mountainside with wind and rain, having a breadth of barely a half mile. It swept away, furious and irritated, under the spur of its lightning flashes, uttering defiance in its peal of thunder. It disappeared from view, ten miles distant, through an open door among the mountains, cresting its summit with living flames.”

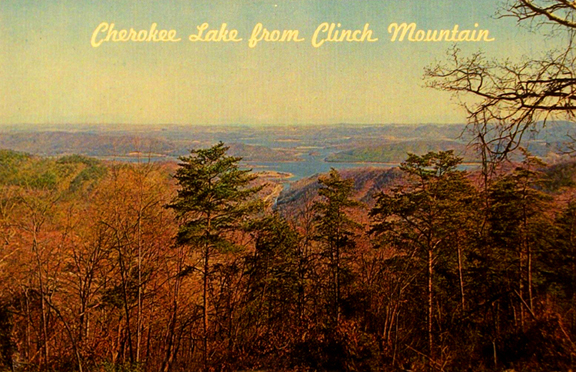

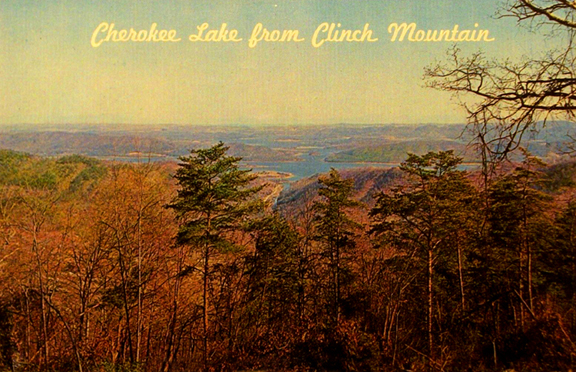

Having worked his way upon the difficult road to the top of the mountain, John sat on his horse with his face turned southward, savoring the splendor of the view. It was exhilarating beyond description; no words could do it justice. The solid ground seemed so distant below as you look down upon it from your lofty perch.

The country stretched as far as the eye could reach, ridge upon ridge and mountain upon mountain. It appeared that some great heavenly plowshare had furrowed up rocky elevations.

To the southeast, the towering Alleghenies marked the division between South Carolina and Tennessee and extended far down into Georgia. They could be traced until they vanished into the dimness of distance. Their majesty inspired the traveler as he or she observed clouds resting upon their shoulders or clinging to their craggy sides.

Although hasting down the steep side was not so difficult, it was certainly more dangerous than the ascent down the rocky slope and across a bed of rolling stones, each particular one having been washed free from the earth by countless rains. If someone’s horse should slip, that person could plunge blow at the risk of their life.

Doe had yet 15 miles to leave behind before he could rest. After traveling six miles, he finally reached the Clinch River, over which he rode after summonsing a nearby ferryman. He noted that the ferry represented the common style in vogue for crossing streams of water. The flat bottom device measured 8 feet wide and 30 feet long. A rope had been attached to each side of the river. This constituted the entire mechanism. The centerpiece was the ferryman, standing proudly in the front of his craft, drawing hand over hand upon his line, while his propulsion was generated by his steadiness and firmness of footing.

It being nearly sundown, John made haste to complete the final nine miles of his journey. At 8 p.m., he entered the little village he had once so well known long ago where he knew that friendly hands would be eagerly waiting to greet him.

Thanks for the trip, John. I wish we knew your real name.

Comments are closed.