Around the end of the 19thcentury, northerners beat summer heat and annoying flies by vacationing in the relaxing pristine southern mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina, known as the “Land of the Sky.”

In early July 1898, H. T. Finck, a New York resident, traveled to Roan Mountain on a mountain railroad that traveled over what he deemed the “Cranberry Road.” The 40-mile long million-dollar endeavor was fabricated to transport steel. It picked up Mr. Finck at the Southern Railroad in Johnson City and chugged along toward his anxiously awaited destination.

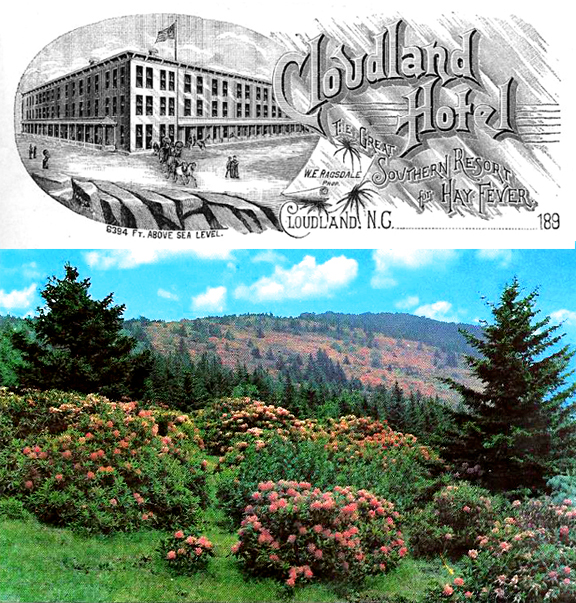

After disembarking at Roan Mountain Station, he took a 12-mile stagecoach ride that was often used in tandem with trains to the top of the mountain at 6894 feet above sea level. Had Finck made the journey a couple of weeks earlier, he would have witnessed the stunning Catawba rhododendrons in full bloom.

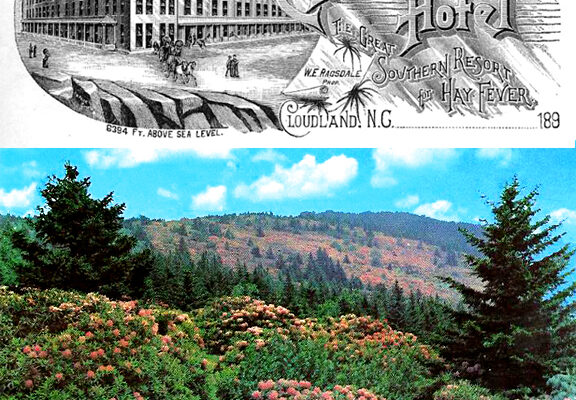

The Cloudland Hotel was the tallest building east of the Rocky Mountains. The state line, dividing North Carolina from Tennessee, passed through the dining room where guests could cut their steak with a knife in one state and eat it with a fork in the other. Also, the rooms were situated such that guests could sleep with their head in Tennessee and their feet in North Carolina.

The building, capable of handling several hundred guests, exposed its broad sides gallantly to the violent winds without using chains anchored to stones like other mountaintop hotels. However, the roof of the Cloudland Hotel collapsed during high winds on two occasions forcing the owners to moor it with heavy rocks. A supreme test of strength occurred in July that year when a violent storm raged for three days nonstop. Although it was the fiercest squall the proprietor remembered in several years, the hotel remained firm on its foundation.

Weather was ideal in summer months with the thermometer dropping to 40 degrees at night, prompting the staff to burn huge logs in all the chimneys. The fires were kept lit day and night for those who desired extra warmth. During the day, the temperature varied between 58 and 64. The hotel was perfect for authors who could work at their trade and simultaneously enjoy the spectacular surroundings. Food in the dining room was not only reasonably priced but also quite succulent.

The hotel was aptly named because clouds afforded the best entertainment when they were not so close as to obstruct the view, as was often the case. The frequent rain that bathed the area usually vanished as quickly as it arrived. Air dampness was exhilarating, not depressing. Just below and behind the hotel was a ravine from which mists formed perfect circular rainbows by the setting sun. Sunsets were magnificently varied and beautiful, painting the majestic sky in all directions.

On some of the mountaintop balds, farmhouses of local residents could be observed. A few curious visitors became acquainted with some of them, whom they described as being perfectly “civil and safe,” except for their curious habit of feuding with nearby families like the stereotyped Hatfield-McCoy feud 20 years prior.

The inhabitants owned sheep, cattle, horses and pigs. Mr. Finck interestingly noted that, while the razorback pig was not an attractive animal, it lived a fresh air life, was fed on unspoiled grass and was bathed daily by unpolluted rains. He reasoned that this was why the animals yielded such well-flavored hams, humorously noting that the critters would stampede down the hill at the mere mention of salt.

A Cloudland Hotel, Roan Mountain stay over around 1900 was truly a wilderness paradise for visitors wanting a break from life’s demanding routines.