When I graduated from Science Hill in 1961, the high school sold one annual, “The Wataugan,” that year for those seniors graduating in May. During 1927-34, the school discontinued the popular publication, later reestablishing it as two separate editions, one in January and the other in May.

The change was prompted by the advent of two separate graduations within the school year, allowing students who successfully completed graduation requirements to receive their sheepskin early. Each one had a commencement exercise and baccalaureate observance. Although my father, Robert Earl Cox, graduated from “The Hill” in May 1934, he left behind both editions from that year.

The January Wataugan comprised 34 pages with 26 graduates while the May edition was 60 pages and had 101 seniors. The Wataugan explained the new concept of mid-year graduations: “For the first time in its history, Science Hill High School is graduating 26 seniors at the close of the first semester. This is of decided advantage both to the seniors and to the school. Heretofore, those students who completed in January the amount of work required for a diploma were forced to return to school in May in order to graduate. Now, by receiving diplomas in January, seniors may enter college for the winter quarter’s work, and the school can make room for sophomores sent from the Junior High.”

Roy Bigelow, Supervising Principal, offered his greeting: “May I offer my congratulations to you as you complete the requirements for graduation from Science Hill High School. I extend them to you first of all because you are inaugurating the plan of a mid-term commencement. Although your group is small, we shall probably see our mid-year graduating classes representing about half of the senior groups. I congratulate you also because you have undertaken to revive the school publication, The Wataugan. May these, along with the joyous experiences of your school career, be cherished memories to you.”

Mary Lee Taylor, a faculty member, provided an explanation of how the school publication received its name: “The name ‘Wataugan’ was officially given to the student publication of Science Hill High on February 9, 1921. Perhaps some word of explanation is necessary as to the reason for the selection of such a title.

“The word is an Indian Name and, early in the history of this section, was applied to a beautiful stream, which flows from mighty gorges, cutting its way through mountain ranges and uniting finally, with the Doe River at the head of Happy Valley. This river quite naturally gave its name to the lovely valley forming the heart of East Tennessee. At this spot, the mountain boys met, proceeding thence to King’s Mountain where they defeated the British regulars in a memorable battle.

“In this same Valley was located Fort Watauga, made famous by Bonnie Kate Sherrill’s thrilling escape from the Indians. The first home on Tennessee soil was erected on Boones’ Creek at the place where it empties into the Watauga River. Still another place of interest is that designated with a bronze tablet, making the famous trail of the pioneer, Daniel Boone.

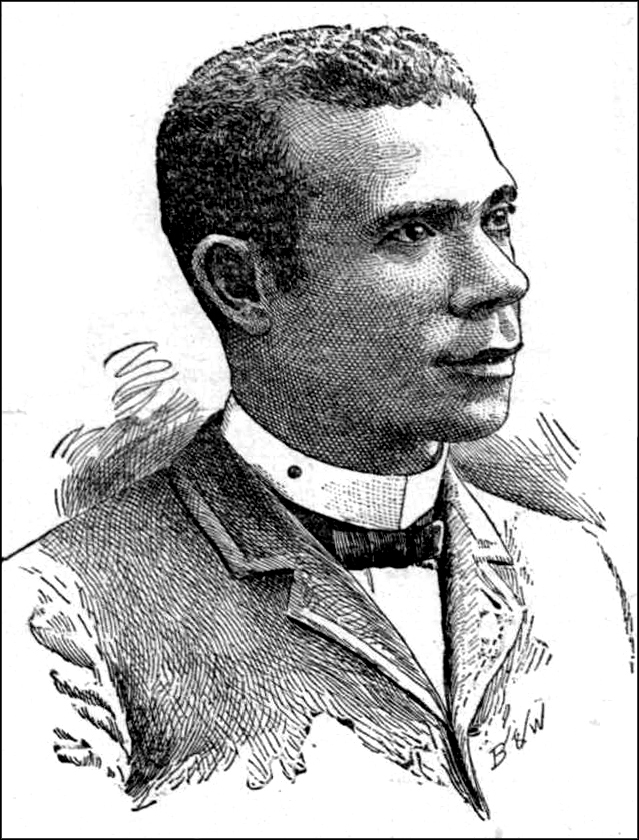

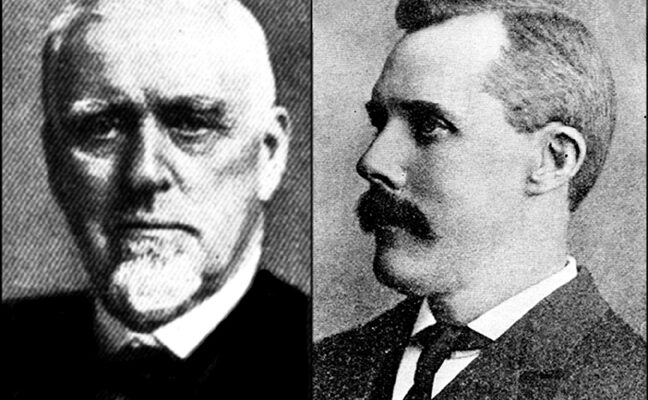

“From the Watauga Valley came the beloved Bob and Alf Taylor who, in other years, figured largely in the life of the state and nation. In more recent times, the renowned valley of the Watauga sent to the front its quota of men who gave their lives gloriously with the famous Thirtieth Division during the World War.

“Wataugan, then, is a name replete with memories of the past and is a most dignified and appropriate title for the publication of a school, which occupies so prominently in the present life of this section.”