In 1947, five local physicians had their practices at 234, 236 and 238 E. Market Street near Tannery Knob (where I-26 now comes through). Doctors George Scholl and Mel Smith were at the first two-story dwelling, doctors Harry Miller and J. Gaines Moss at the second and doctor Ray Mettetal at the third. Unlike the other five doctors, he and his family lived upstairs and had his practice downstairs.

Dr. Mettetal told my parents something that year that would have a profound impact on my life – I had rheumatic fever. The disease is an inflammatory infection affecting the joints and possibly the heart, skin and brain, targeting youngsters between the ages of four and eighteen. I was five at the time and sickly with the classic symptoms of fever, joint pain, fatigue, paleness, lack of appetite, weight loss, a rash and bouts of strep throat.

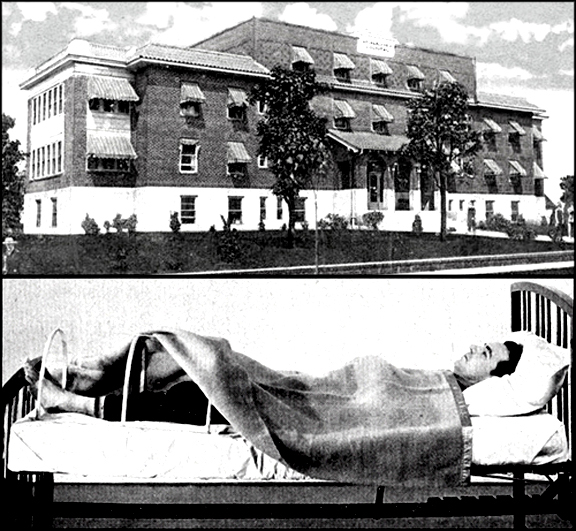

My daily routine quickly began to change significantly. After two-weeks of being quarantined in our smallish apartment, I was subjected to absolute bed rest with limited physical activity. I was not permitted to walk so I had to be carried everywhere I went. Unlike today, almost total inactivity was considered essential to control rheumatic pain and spare damage to the heart.

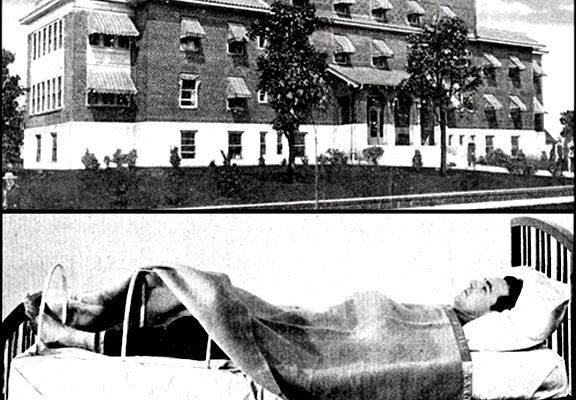

Once a month, I was taken to Memorial Hospital (Boone Street and Fairview Avenue) for a blood “sed (sedimentation) rate test” that measured the amount of inflammation still present in my body. The procedure was performed on the second floor along the north end of the hospital with windows overlooking E. Watauga Avenue.

I grew to dread the needle that was placed in my arm and held there for what seemed like an eternity. The attending nurse always had me look out the windows to get my eyes and mind off the needle. I recall seeing a man on Watauga chase his hat that had blown off from a wind gust. Everyone was laughing at him except me.

For about six months (maybe longer), I spent my days in bed, at our dining room table, in a chair with a bag of toys on our table’s center leaf that was positioned across the arms or sitting in a chair looking out the window of our second floor apartment. I observed traffic below and saw people at the Sur Joi Swimming Pool (107 Jackson Avenue). Sometimes I played 78-rpm records on our old upright radio/record player. A thoughtful young lady, Anna Buda (sister of George Buda), who lived in a nearby apartment, routinely came by with her little dog, Butchie, and let me play with him.

Some time ago, I came across a Metropolitan Life Insurance Company ad in an April 30, 1944 edition of Time Magazine. It featured a young boy (about my age when I was sick) with rheumatic fever in a bed crammed full of toys, books, games and crayons. A young girl was entertaining him with a puppet show at his bedside. The ad emphasized the need to keep patients fully occupied until all signs of the disease had cleared up. Entertainment, it said, was the best medicine a patient could receive.”

A second advertisement in a February 1944 edition of Good Housekeeping Magazine showed a mother privately talking to the doctor with a young boy in bed in the next room. It consisted of solemn questions and answers between Mrs. Roberts and the physician.

Until 1960, the disease was a leading cause of death in children and a common source of structural heart disease. Although the malady had been known for several centuries, its association with strep throat was not made until 1880. In the 1930s and 1940s, rheumatic fever was a serious medical concern for adolescents. With the discovery of penicillin followed by a plethora of other antibiotics, patients could then be treated adequately.

The end of my illness meant learning to walk again. My dad held my arms much like he did when I took my first steps as a toddler. I was assigned the morning session of Miss Taylor’s first grade class at West Side School because I needed an afternoon nap. In 1950, we moved from our apartment to the “wide open spaces” of Johnson Avenue. My new active lifestyle of running and playing was a thrill that is firmly embedded today in my memory.