In the late 1940s, representatives of the American Broadcasting Company came to Johnson City to tape a live radio program from Big Burley Warehouse on Legion Street. The remote was from ABC’s popular “Ladies Be Seated” series that aired weekdays at 3:30 p.m. from Radio City in New York.

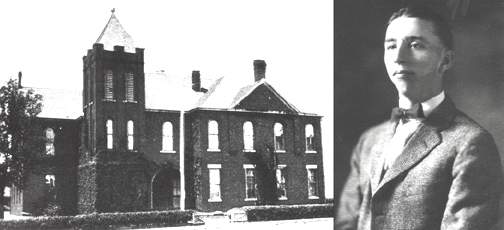

In the audience that afternoon was a youthful Merrill Moore who later became anchorman at WCYB-TV in Bristol. According to Moore, “It was a big thing for me to get to attend this show. They constructed a stage in one section of the warehouse and put up seats for an audience.

“It was not unusual during this time frame for network radio stations to set up in remote locales so fans could attend their favorite radio shows and observe their esteemed emcees in person. A sizable crowd showed up for the event.

“Johnny Olson was emcee and was assisted by his wife, Penny. He later switched to television and hosted several television shows over the years, including working with Bob Barker on ‘The Price Is Right’ as the familiar announcer who repeatedly told participants to ‘Come on down.’”

“‘Ladies Be Seated” was primarily a ladies variety program. “I remember that they went into the audience, interviewed people, told jokes and gave away prizes. The format was similar to ‘Don McNeil’s Breakfast Club’ and ‘Luncheon at Sardi’s’ (1947 broadcast of live audience interviews from Vincent Sardi’s Restaurant in New York).”

A typical program opened with merriment from the audience, the prompter telling a joke and spectators singing the opening theme, “You Are My Sunshine,” to the accompaniment of an organist. Announcer Walter Herlihy opened with “It’s fun time across the nation. Yes, if you have some chore to do, somewhere to attend to, some job that needs completing, you’ll do it all the better and enjoy it all the more after listening to today’s game edition of ‘Ladies Be Seated.’” He then proclaimed to the audience with drawn-out words: “Ladies … Be … Seated.”

Walter next introduced the show’s host: “Good afternoon ladies and gentlemen, this is Walter Herlihy welcoming you to another of your favorite afternoon parties sent to you each weekday at this time from New York. Yes, it’s time for the ladies to be seated and the gentlemen to join in our festival of fun. And to start our party, we bring you a man of the world, a gentleman who has been on every street but Bradstreet and will never get there because he laughs at money and pays money for laughter. And here he is, Johnny Olson.”

Olson respond, “This is Johnny Olson sending greetings to the men in the street, the housewife at home and advising all our friends everywhere that putting a smile on your face is right up my alley and we are going to try to prove it with today’s edition of ‘Ladies Be Seated.’”

The participants were mostly women. Typical entertainment included a lady alternately answering questions from Olson one moment and singing a verse of “Meet Me Tonight in Dreamland” the next, a husband and wife acting like love sick dogs while Johnny read a script and contestants awarded prize money for singing as determined by an applause meter, husband and wife blindfold gags and musical quizzes.

The program evolved from a show first heard over NBC’s Blue Network in 1930 as “Sisters of the Skillet,” featuring a parody of household hints. In 1944, the name and format were changed to a weekday 30-minute series. The show, sponsored by Quaker Oats, gave away about $6,000 worth of merchandise each week. “Ladies Be Seated” went off the air in 1950.