About 1955, my dad sparked my interest in a unique leisure pursuit when he brought home a “Paint by Number” kit, consisting of two French city scenes. Each canvas was solid white and subdivided into numerous small areas, each containing a light blue handwritten number. In order to bring the picture to life, the artist had to paint it. The product was cleverly advertised as “Every Man a Rembrandt.” (Sorry ladies.)

The instructions said to match the paint color number with the pallet area number and apply the coat evenly without crossing lines. Over the next several weeks, I watched Dad meticulously transform both white canvas boards into beautiful works of art. He was proud of his creation and so was I, as evidenced by my displaying them on my bedroom wall for several years.

Completion of a kit was not a frivolous overnight undertaking; it took weeks to finish one, especially if you planned to frame and hang it on a wall or use it as a gift. In actuality, its true value was measured by the person who painted it. Unlike watercolors that we became accustomed to as children, PBN kits utilized oil-based paint requiring the user to exercise caution so as not to get paint on everything. Brushes had to be kept in mineral spirits when not in use to prevent them from becoming dry.

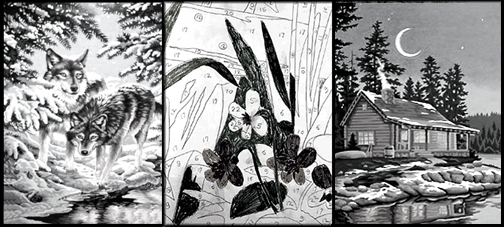

One trick was to chose a color and paint all the sections on the canvas that contained that number. Properly done, the beautifully dried painting was a testimony to the painter’s patient efforts. My first two paintings as I recall were “Blue Boy” and “Pinky,” popular subjects of that era. Neither of them ever graced anyone’s walls.

PBN kits did not enthrall everyone. Some critics viewed them as a form of mindless compliance of the masses by going through the motions of rote and expressionless labor that totally removed the painter’s creativity from the equation. However, others found the projects as intriguing introductions to painting for people not familiar with using oil-based paint.

In reality, the kits offered a sliding scale compromise between total creativity of painting freehand and having the security of a template. Many people deliberately altered the instructions and purposely painted over lines, removed specific objects from scenes and even changed color schemes, thus injecting a bit of imagination into the project.

The love affair with numbered paintings extended to the Eisenhower White House when then secretary Thomas Stephens collected PBN paintings from staff members and friends and displayed them in a West Wing corridor.

The Paint By Number phenomenon originated in 1950 when a Palmer Paint Company employee, Dan Robbins, devised a clever way to help his business sell more paint. It came at an opportune time because postwar America was experiencing a sweet taste of the good life – free time, increased wages and a thirst for recreation.

After a rocky beginning fraught with numerous problems, the product experienced a meteoric climb in popularity, selling more than 12 million kits between 1951 and 1954. It was estimated that during this time American homes contained more PBN pictures than original works of art.

In the early 1990s, after several years of decline, the product came full circle and showed signs of popularity once again. Today, the do-it-yourself kits can be found in the craft section of some stores. Vintage paintings frequently are displayed in antique stores, rummage sales, flea markets and auctions thus demonstrating their longevity.

Comments are closed.