A Johnson City Staff-News writer, Carroll E. King, took an East Tennessee and Western North Carolina (Tweetsie) Railroad pleasure trip on July 9, 1933 between Johnson City and Linville Gap, North Carolina to enjoy the stunning, rarely seen surroundings that were inaccessible by automobile.

King berated himself for not having enjoyed the trip many times before, describing the ride through the gorge and over the crest as being as beautiful as is possible over the ET&WNC Railroad. He urged his readers to avail themselves of the railroad’s special 50thanniversary July rates. Sights included the famous Doe River Gorge, Skyland, Grandfather (Mountain) and other points from the vantages of the railroad. To persuade people to ride the train, he published an alluring diary of the trip:

“Leaving Johnson City, we secured a view of our own local industries not visible by any motor road. Then we climbed up and looked down over Happy Valley and its real beauties never before appreciated.

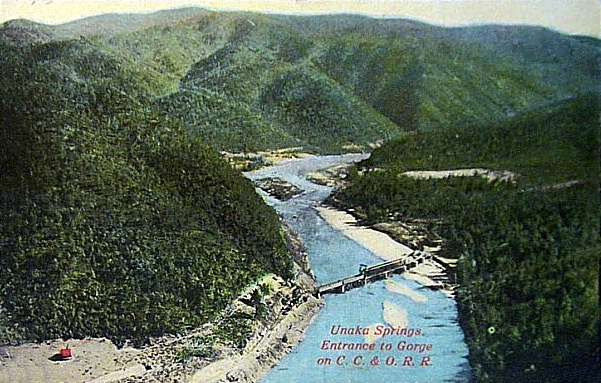

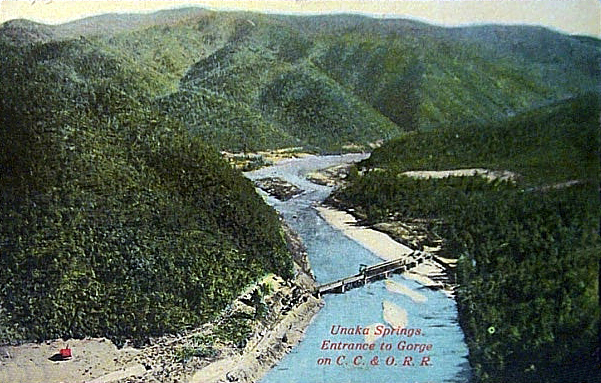

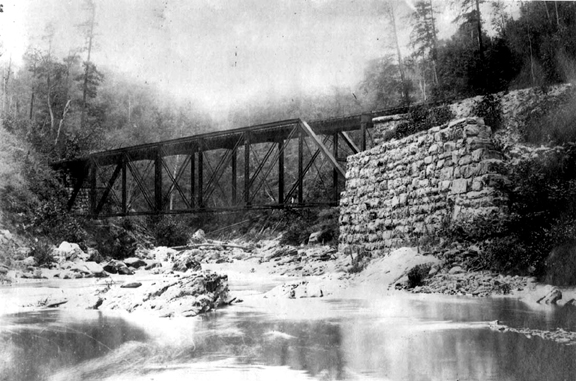

“Elizabethton followed, then Hampton and next the little newly painted and all shined up engine got right down to business. It was upgrade with a vengeance and within a short time we passed through the tunnel that led into the Gorge, a treat that no one who has not seen it can really appreciate.

“Tracks carved out rock walls, tumbling torrents at our feet, towering mountain walls of anticline rock formations and gorgeous vistas of mountain scenery elicited “oohs and aahs” from the passengers. Indeed the Gorge is a scenic gem that cannot be described. We tried in vain to get Kodak pictures to prove our claims, but the canyon is so deep and shadowy that pictures can hardly be taken because sunlight seldom reaches its depths. But it is wonderful and we unqualifiedly recommend it.

“Then up the hill and further up the hill (we went) until the bracing air and the bright sunshine cause one to dig into the lunch basket long before the anticipated time. Roan Mountain, with its beautiful resorts, high mountain peak and world-famous dahlia farms came next. Then Elk Park, bracing with its cool, clear air and invigorating climate, was closely followed by Cranberry, the home of famous Cranberry Iron Ore. There we dropped one passenger car in order to relieve the game little engine of the extra load on the upper reaches of the mountain.

“From then on, we climbed higher and higher until we reached the very crest of the Great Smoky Mountains and could look down on town after town and enjoy gorgeous vistas of mountain scenery in brilliant sunshine. Innumerable opportunities are afforded here for Kodak shots because the steep grades slow the train down to such an extent that “Kodaking” from the train becomes an interesting pastime.

“Next comes the famous summer resort, Linville, with its magnificent hotel, rustic cottages and nationally famous golf course. Several passengers alighted there to play a round on the noted course, but we felt that we could play golf any day and we wanted to see all there is to see. So we struck along and journeyed on Linville Gap some few miles further and it was well worth it.

“Linville Gap is nothing but a wild spot in the mountains, right at the foot of Grandfather Mountain and is the highest spot east of the Rocky Mountains that is reached by a railroad. Its elevation is 4,113 feet and you can look right up at another slope of several thousand feet between you and the top of Grandfather. But fortunately for physically weak city dwellers, lumbermen of that section have built a tram road or “log highway” to within a half-mile of the summit.

“These split logs have been laid with the smooth side up – one end embedded into the mountain side and the other resting on trestle work. Automobile trucks carrying acid and pulpwood logs dash recklessly up and down this road. We declined with thanks the opportunity to ride and insisted on walking. Although we might be termed a coward for not riding the trucks, we got a far bigger kick out of walking up the tram road studying the flora and fauna and picking gorgeous wildflowers and luxuriant ferns.

“Miles up, it seemed we came to a trickling waterfall and there we spread our picnic lunch. And were we hungry. The writer has as his guest a couple of youngsters and one young lady being an Ohio citizen was not very familiar with the high altitudes. Frankly, we were somewhat fearful of her capacity as she devoured sandwiches by the dozen not by the bite. Dyspeptics are urged to take this trip as a sure cure. If you cannot eat after climbing half of Grandfather Mountain, you are hopeless.

“Then, with the lunch baskets and the canteens much lighter, the climb was resumed with every widening vistas of beautiful scenery and awe-inspiring structures of nature. Realizing that the return trip must be started at 3 p.m., we reluctantly ceased our upward journey and retraced our steps with the pronounced conviction that we would return soon and this time go all the way to the top. And to our amazement, the return trip was equal if not the superior of the up-trip because all of the scenery was viewed from a different perspective.

“Here and now, it becomes our pleasant duty to express our appreciation of the keen personal interest taken in the entertainment of the passengers by the members of the train crew and the officials accompanying the excursion. Nothing was left undone that would enhance the pleasure of the trip. Constantly crew members were busy pointing out interesting views and historical spots and every few minutes some member would make the rounds to see if everyone had everything he or she wanted.”

Carroll King reminded his readers that another excursion would be offered by the railroad line the following Sunday at 8 a.m. and urged them to take advantage of the reduced rate opportunity. Based on his excellent write-up in the newspaper, the next excursion was likely full.