The Nov. 4, 1918 Johnson City Staff offered enlightening news about the First World War (July 28, 1914 – Nov. 11, 1918). Here is a slightly paraphrase of the commentary:

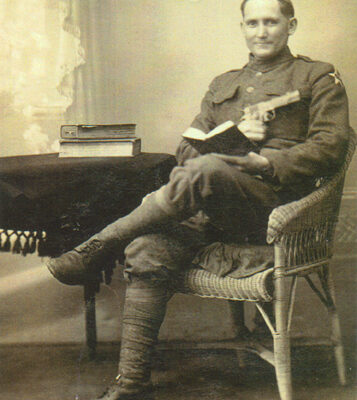

face and hands tanned to the shade of his brown khaki, hat string hanging behind his head and an insolent kind of jaunt as he lumbers his way through crowded streets.

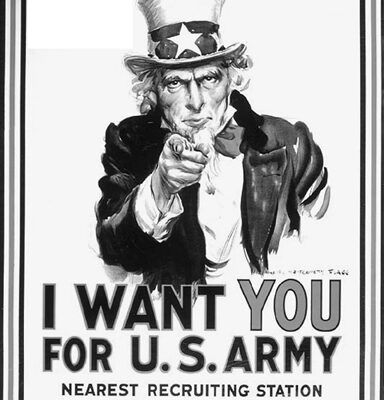

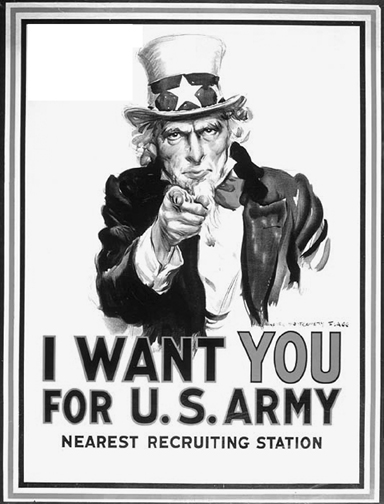

We observe something in this fellow that makes us want to take off our hat to him. In the first place, he has passed a strict examination by Uncle Sam. This is something in his favor for our Uncle is no easy man to please in these troubled days.

The rejects are numerous because a man must be a good specimen and be sound in limb, heart, hearing, eyesight and general makeup. Government acceptance of a man is a good certificate of character. He is a well set-up sort of chap and seems to have no trouble looking the world directly in the face.

The soldier has had training, which is displayed in his rhythmic swing as he walks. He can stand up straight and when he stops, he is able to stand as still as a rock, with no lounging, no fumbling with hands, and no fidgeting from one foot to another. He displays self-confidence.

The soldier has himself under control. He stands for his country, for you and me and he knows discipline. He stands ready at quick notice to come, to stay, to go to the end of the earth, when his country calls.

If its to guard a bridge, he's there and digging trenches is all the same to him. If there becomes a need to man the trenches or go on the firing line, he's always ready. He goes where and when he is needed without hesitation. Because he is a disciplined soldier, danger means nothing to him; it's all in a day's work.

The soldier is the world's true optimist; some of the others might not make it back home, but he'll be sure to come back. Perhaps the soldier has a mother, wife or sweetheart. What matters is that he's a soldier with a job to do and he does it.

Staggering as are the totals of killed and wounded on the battlefields of Europe, the fact remains that the hazard of the soldier in France was mathematically far below that faced by a participant in the previous Civil War.

In one month of bombing and trench warfare, France and Great Britain lost 114,000 men killed and wounded, according to authentic reports which was said to make the world throw up its hands in horror.

But when it is remembered that a total of 2 million soldiers were engaged and subject to the same dangers to which their 114,000 comrades fell victim, the percentage of casualties is brought down to less than 6 percent.

However, during the Civil War, after 12 hours of fighting at Antietam, 23,000 Union and Confederate soldiers were killed or wounded, being 20 percent of the forces engaged. And taking the war as a whole, the degree of hazard of the Civil War soldier was almost four times as great as was that of the soldier in France.

Military experts tell us that if the armies engaged in the greatest of all wars had continued to follow the open warfare methods that marked the early days of the war and characterized the methods employed in the Civil War, the opposing armies long ago would have been annihilated.

It should be remembered that the original army that was sent to France by England at the beginning of the war was practically destroyed during the first six months. That was because they pursued open warfare tactics. But the successors of those unfortunate fellows soon learned to dig themselves in, with the result that the percentage of casualties was greatly decreased.

In summary, the soldier in France stood a far better chance of coming out alive and whole of body than did the soldier of the Civil War.