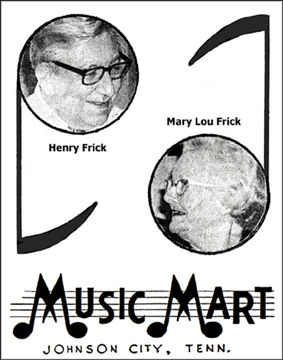

Four Responders Reflect on Frick’s Downtown Music Mart

My recent Music Mart article brought response from four people, Robert Bowman, James Edens and two people identified only as Mr. A and Mr. B.

Mr. A stated, “Henry Frick was a perfectionist, an intelligent merchant and a skilled craftsman who demanded nothing less from his employees. Nevertheless, he was a compassionate gentleman whose place of business reflected his noble character. Area piano teachers and bandleaders knew where to go for all their music-related needs: the Music Mart.”

Robert Bowman, who worked there from fall 1963 until spring 1966, remembered the close-knit couple “coming back from lunch, hand-in-hand, like high school sweethearts, usually bringing with them a new idea for the business.”

“Since it was the Music Mart on which band members from most local schools relied for upkeep of their instruments, Henry and Gary Phillips were kept steadily busy as repairmen six days per week.

“As a courier, I spent many hours out of the store, getting defective instruments to the post office for safe shipment to the appropriate factory, chauffeuring the youngest Frick daughter on designated Saturdays, getting Frick's car washed and picking up the family's dry cleaning.”

In my first article, I noted Henry’s unique dry humor. Robert supplied another example: “I was also responsible for dusting instruments and displays. One day, Mr. Frick approached me and said ‘Are you saving this dust for any reason?’

“Gene Young traveled throughout northeast Tennessee and southwest Virginia to elementary, junior high and senior high schools, collecting defective instruments and delivering restored ones.

Bowman's successor and former neighbor, James Edens, made this comment: “You could set your watch by Gene's arrival. When that van pulled in, it was about time to lock up and go home.”

“Toward closing time each day,” recalled Robert, “every staffer was assigned to put vinyl records back into their proper sleeves after listeners usually left the discs in disarray. The store had private audition booths equipped with headsets that were liberally used by many junior high, senior high and college students.

An anonymous former hired hand, Mr. B, recalls the entire staff taking inventory annually on January 1: “The unpleasantness of this unwelcome ritual quickly subsided when Mr. Frick treated us mentally tired laborers to a delectable meal at the Dixie Drive-In Restaurant. The only negative element of these dining experiences was our boss man's insistence on celebrating the new year by every one eating black-eyed peas. I nearly choked.”

“Perhaps Mr. Frick's tolerance toward all youth,” said Bowman, “including those happy-go-lucky ones who often ‘parked’ in the sound booths for extended time spans, can be attributed to his hope that some of the hearers would become players, transforming mayhem to melody. From the wise man's perspective, negative behavior of these non-buyers, whose loud conversations distracted customers, might be eventually channeled into desirable activity, such as mastering a horn or a keyboard.”

Robert concluded with picturesque words: “A stroll down South Roan Street today yields no vestige of the little Music Mart. Yet, in the mind's eye, one can imagine the enterprising Henry puffing on his pipe, each smoke ring signaling an innovation for his beloved store while his soul-mate flashes a sweet smile of concurrence.”

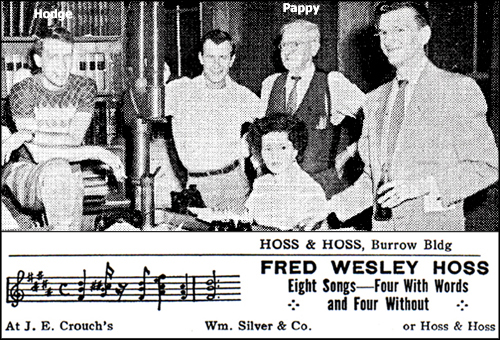

and 1950 Ads-1050x400.jpg)