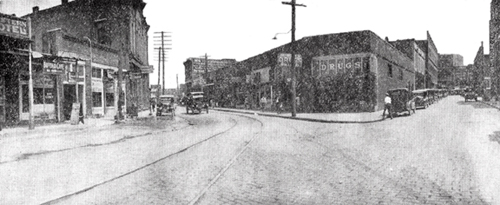

One piece of exciting news in 1912 was the opening of Jones-Vance Drug Company at 121 Buffalo at Tipton. There were just four doctors in town then – Dr. Elmore Estes, Dr. J.H. Johnson, Dr. W.G. Matthews and Dr. J.H. Preas.

Owners H. Raymond Jones and T. Beauregard Vance took over the site formerly occupied by the Abraham Heller Cigar Shop. This was in the era of Model T cars, brick streets and trolley cars. Jones had ten sons and over the years employed them as they became old enough to work.

A 1915 Chamber of Commerce booklet described the business as “a beautifully fitted up store, which reflects credit alike to the city as well as to the proprietors.” The publication further stated, “It may be said that there is no branch of business, which, for its successful operation, calls for such a high standard of character, combined with sound knowledge and ripe experience, as the modern drug business. This store is thoroughly stocked throughout with every variety of drugs, sundries, medicines, toilet articles, perfumes, cigars and all other such articles usually found in first class enterprises of this character.”

In 1969, the late Dorothy Hamill, former Johnson City Press-Chronicle writer, interviewed Lloyd Jones, the only surviving son. He noted that although his family’s trade changed hands several times during its 68-year operation, it always carried the original name. His store duties included helping prepare medicine, working at the soda fountain and dispensing a wide variety of patent medicines. Jones recalled that the hours of operation were from about six a.m. until nine p.m., seven days a week.

On the left side of the store as you entered was a counter that displayed boxes of candy, stationery, chewing tobacco, cameras, perfume, postcards, cosmetics and the like. On the right side was a beautiful soda fountain fabricated of marble and onyx. “There wasn’t any refrigeration then,” Jones said, “We kept the ice cream in ice and rock salt and made our own chocolate syrup. Customers could buy chocolate milk for five cents. It consisted of ice cream, chocolate syrup and milk, all mashed up together. You could get a banana split for ten cents. At the end of the fountain was one of those decorated china lamps that looked like stained glass.”

Lloyd indicated that fountain customers were served at one of three round wrought iron tables at the far end of the store. Notably absent were counter stools, considered to be out-of-place for a quality drug store. Ironically, not considered rudimentary was a brass spittoon (or cuspidor) sitting on the floor just inside the door to the right, adjacent to the soda fountain counter.

Air conditioning consisted of an overhead fan for summer months and a coal burning stove in the back during cold weather. Hot pipes from the stove ran under the ceiling and had to be cleaned periodically. The remedy was to wrap sulphur and nitrate of soda together and burn them in the stove to eliminate the residue in the pipes.

Getting a license then meant serving as an apprentice to another druggist for a prescribed period of time. Medicines were prepared in a back room by the pharmacist. He charged 50 cents to fill a prescription plus the price of the drugs. If people wanted pills, the attendant would mix and grind the powders and place them in capsules or small paper folders. The store’s original mortar and pestle were eventually donated to ETSU’s Reece Museum.

Jones-Vance made some of its own remedies such as tincture of iron and iodine, a cough medicine containing mostly honey and laudanum (opium), a blood tonic called IQS (iron, quinine and strychnine), a liniment rub comprised of mostly grease and cayenne peppers and another tonic known as VVP (vim, vigor and pep). The drug store also sold several patent medicines such as Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound and Cardui, “The Woman’s Tonic.”

The close proximity of the business to the railroad resulted in customers arriving in Johnson City by train from Virginia and North Carolina and patronizing the store, often bringing with them orders from the train conductors. These would be filled and taken back to the depot the same day.

Hungry customers desiring more than fountain fare usually went across the street to the Buffalo Café that was operated by an older lady. The eatery’s placard consisted of a single board containing the menu. In addition to short order items, regular dinners cost 35 cents and Sunday ones sold for 50 cents.

City directories reveal that Jones-Vance moved to 110 E. Main between 1928 and 1935 on the site formerly occupied by Gump’s clothing emporium (downstairs) and Jobe’s Opera House (upstairs) and later the Tennessee National Bank.

While few residents can remember the Buffalo Street store, many can recall the impressive Main Street one. The business remained in that location until its demise in 1960.