In 1896, the area where Oak Hill Cemetery would later be built was a wilderness of unkempt weeds and briers. A number of small animal pens were located there, along with barbwire that served as a perimeter fence.

The property was anything but attractive; it was also, in fact, untidy pasture land for the town cow and was a “disgrace” to the city. Soon, a committee of ladies from each of the city churches met in the home of Mrs. C.K. Lide and planned how to raise money for a nice cemetery fence.

With an oyster supper, a lecture from Senator Robert L. Taylor and another from Honorable Alfred A. Taylor, enough money was raised to build a substantial fence around the burial ground. “Oak Hill Cemetery Association” was organized November, 1896, with Mr. C.K. Lide as president.

A monthly meeting was held in the homes of different members, offering an occasional ice cream and strawberry festival, musical concert or the like. Unfortunately, it raised barely enough money to handle the weeds and briers and pave a narrow driveway through it.

The president moved away and the meetings were discontinued until Oct. 28, 1904. At that time, the ladies were called together in the home of Mrs. C.E. Faw and the association was reorganized with Mrs. W.J. Exum as president.

The group met with discouragement, criticism and was faulted for their lack of progress, but they persevered until they began to feel pride in their work. Their efforts inspired J.C. Mumpower, their sexton who bore his share of the censure, to agreed to serve another season.

The public apparently never realized that during the summer, the sexton couldn't mow the entire cemetery in a day, get on his knees and clip grass from around graves, trim around corner stones and cut in such places as could not be reached with the mower.

All of this was in addition to possibly having to dig three or four graves in the same timeframe. By the time the poor worker mowed the entire ground, the cemetery was needing mowing again and sometimes needing it badly, especially if the weather was prohibitive.

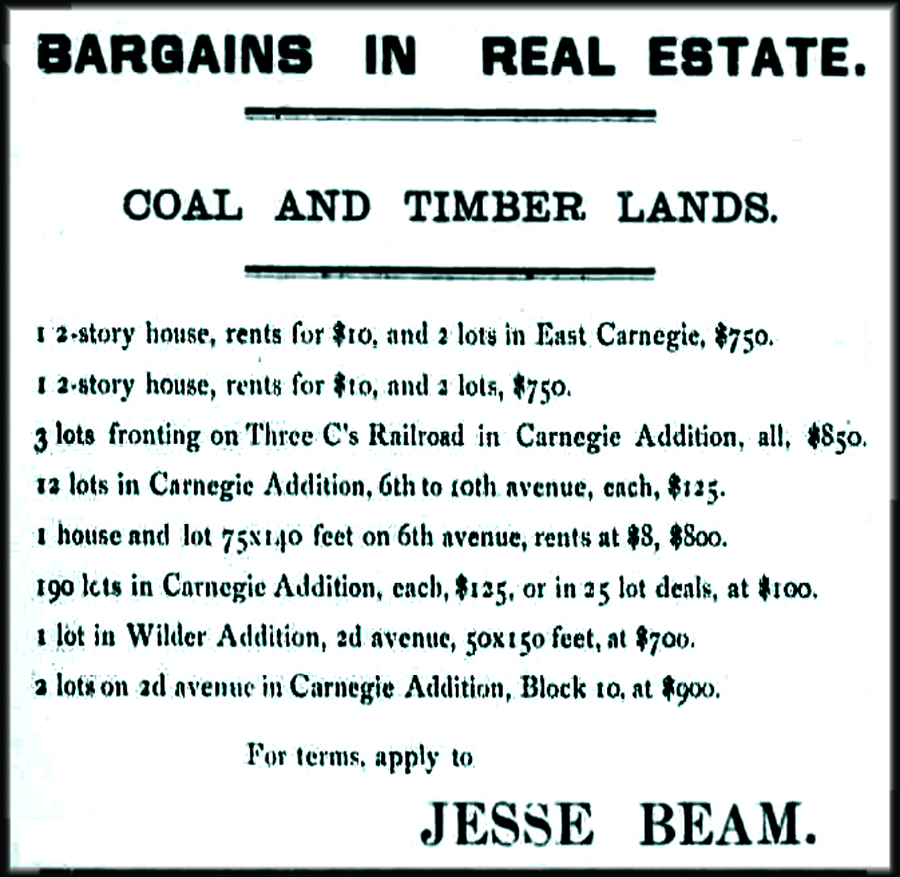

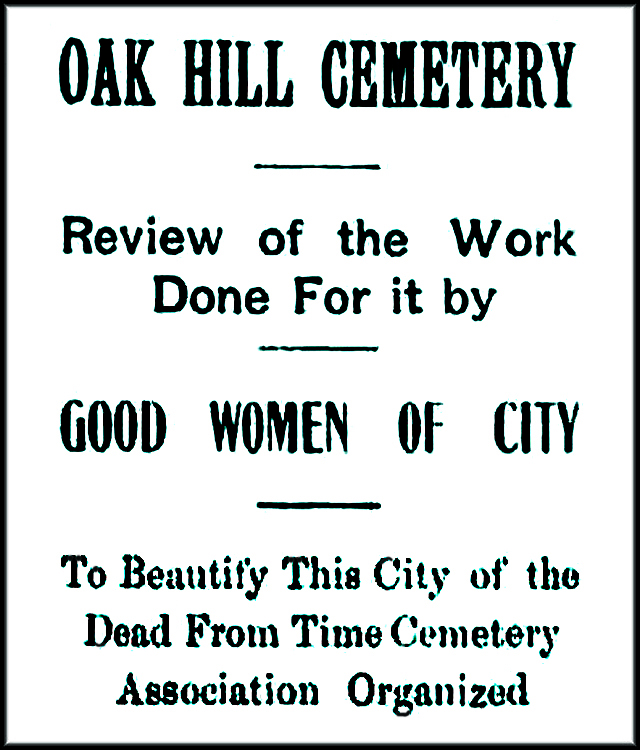

Oak Hill Cemetery Advertisement from June 4, 1908

Often, a visitor would visit the cemetery only to find his or her departed loved ones resting in a particular spot that needed attention. He or she would go away with hurt feelings, believing that their cemetery space was not being mowed regularly while other parts of the cemetery looked nicely groomed.

The individual often made an appointment to see the president or another officer of the association and tell them their square was not being kept up as it should. They argued that they paid their $1.20 annual fee the same as others, but lacked proper service. Sometimes, in a fit of anger, they would ask that their name be taken off the book, electing to either take care of the unkempt plot themselves or hire someone to do it.

It was noted that such individuals needed to visit the cemetery more often in order to get a truer picture that their plot of land received the same good care as all of the others. The visitor would, in turn, go away feeling much better that proper work was indeed being done.

Saturday, May 30, 1908 was decoration day. The sexton was especially anxious to have people travel to the cemetery on that day, expecting to do his best to have the grounds in tip top condition. The cemetery team asked those who attended that day to offer encouraging words to the sexton and others, thus making them feel their efforts were appreciated.

The officers that year were Mrs. J.A. Martin, president; Mrs. Frank McNeese, vice-president; Miss Sallie Faw, Treasurer; and Miss Nellie Kitzmiller, secretary.

I would be amiss if I failed to mention the late Chet Willis who selflessly volunteered his services at the cemetery for several years that included opening and closing the gates daily. Alan Bridwell and I have not forgotten this steadfast gentle giant who left us in the summer of 2008.