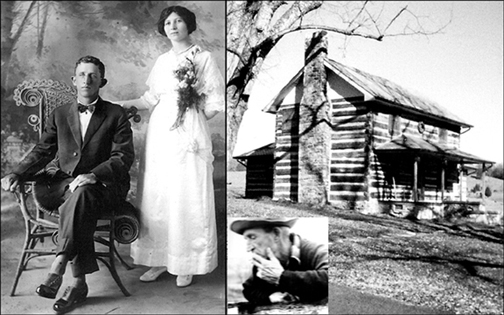

Ray and Norma Henry, former area residents, recently recalled when the peaceful early morning hours of July 10, 1950 suddenly turned into a ghastly scene of carnage that claimed the lives of three local people.

Ray picked up his sweetheart and future wife, Norma Murr, at Telford in his solid black 1938 Chevrolet 2-door sedan and drove to Johnson City to take in a movie at the Sevier Theatre (113 Spring Street). Being Sunday, the business was not permitted to open until 9 p.m. Norma remembered standing in a long ticket line outside the theatre that stretched back toward Main Street. When the movie ended at about 11 p.m., the couple drove to Nave Drive-In (200 Delaware at W. Market) for a snack.

Afterward, Ray headed back to Telford on 11-E to take Norma home. At about 12:45 a.m., just minutes after the couple passed the interception of Highway 81 to Erwin and the American Legion Club (formerly Woodland Lake) on the right, they spotted a bright light flashing across the sky behind them. Simultaneously, they heard what sounded like a motorcycle revving its engine. Believing a biker had run off the road, Ray turned the car around to investigate.

As they approached the Club, they spotted Joe Fleenor, the custodian who lived there, running back from the wreck to call for help. He hurriedly told them that there had been a horrific bus and car collision there. Ray and Norma drove to the wreck scene and parked along the side of the road. Since it was pitch dark, the couple took a flashlight from their car and crossed over a damaged barbwire fence by using a wooden sty that had been built there.

The bus, a Tennessee Coach express en route to Birmingham, was heading to Knoxville. The other vehicle, a 1948 five-passenger Ford coupe, was reportedly traveling to Cosby. When Ray and Norma reached the bus, they observed the driver, Jimmy Lowery, helping his 38 passengers exit the vehicle. Surprisingly, no one appeared to be injured or overly alarmed. After the bus was emptied, the passengers huddled together until another coach could be dispatched.

Lowery indicated that the Ford had attempted to pass him on a straight stretch of highway but briefly ran off the left side of the road and immediately swerved back along the left front of the bus. Jimmy tried to avoid hitting the car, but their bumpers suddenly locked together, sending both vehicles through the fence, down a 6-foot embankment and skidding 100 yards in a field before coming to rest. Fortunately, they missed several trees and Barkley Branch Creek or the circumstances would likely have been much graver. The bus landed upright on its wheels directly over the car that was upside down and barely visible.

About that time, Joe Fleenor returned saying that help from the Sheriff’s Department, Highway Patrol and Rescue Squad was on the way. Lighting was installed to illuminate the wreckage area. Dillow-Taylor Funeral Home provided two hearses that also served as ambulances. Three wreckers arrived. Two drove down the embankment to the wreck site while the third one stayed on the road to later pull the first two back onto the highway.

Over the next agonizing minutes, one wrecker slowly pulled the bus forward while the other one partially dragged the car from under the bus. At first, it was impossible to determine how many people were in the car or who was driving. One person was still alive and in obvious pain.

Initially, it appeared that there were two occupants. Then Norma spotted another body in the back seat of the wreckage. All that could be seen was her red hair. In order to free her, workers had to carefully pull the coupe farther away from the bus. It was quickly confirmed that the woman was deceased.

Ray described the wreck as gruesome, saying it was the most sickening one he had ever witnessed. There was virtually no means to help the car occupants because they were literally compressed in a heap of metal and flesh.

The Johnson City-Press Chronicle’s Monday evening edition provided additional facts about the crash. The passengers were identified as Carl “Cocky” Cox, 45; John Monday, 35; and Nettie Patterson, 26. Monday’s body was removed first because he was still alive, but he passed away at Appalachian Hospital (300 N. Boone Street) in Johnson City at 3:30 a.m. One item of interest found in the car was a blood-soaked small brown bag containing $2700 in bills.

Cox’s lifeless body was next removed from the wreckage. Ray recognized Carl’s face, removed his wallet and handed it to a patrolman. His driver’s license confirmed his identity – Carl Vernon Cox, Limestone, Tennessee. The investigating patrolmen speculated that Monday was the driver. Sergeant Jim L. Seehorn of the Tennessee Highway Patrol said the vehicle was crushed like an accordion, having an astonishing vertical height of 18 inches.

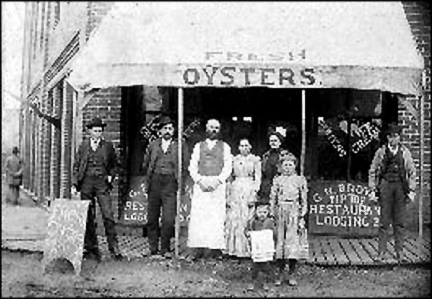

Cox, a well-known, colorful businessman of that era, operated nightclubs in the surrounding areas at various times in his career. In September 1947, he was arrested after the Highway Patrol raided the Mott-O Club that was located on the west side of the Kingsport Highway not far from the Kingsport/Bristol intersection, seizing liquor and gambling equipment. Cocky received a 6-month jail sentence and was fined an undisclosed amount of money. A large number of Johnson Citians rallied behind Cox and partitioned Governor Gordon Browning. They convinced him that politics figured heavily in the raid and that Carl deserved to be excused. Consequently, the state’s chief executive issued a pardon after Cox had served only two days.

Monday, a World War II veteran, had been a driver for Diamond Cab Company (116 Buffalo) for about 10 years. Mrs. Patterson, the mother of three children, was a waitress at Central Bar-B-Q (701 S. Roan).

Appalachian Funeral Home (101 E. Unaka) handled arrangements for all three families. Funeral services for Peterson, Cox and Monday were held respectively at Highland Christian Church, Watauga Avenue Presbyterian Church and Temple Baptist Church.

Although 60 years have come and gone, there are still senior citizens around who remember that dreadful early morning event of summer 1950. Ray and Norma Henry are two of them.

(Note: Carl “Cocky” Cox was Bob Cox’s second cousin.)