“Clang, clang, clang went the trolley; Ding, ding, ding went the bell.” These familiar words are from “The Trolley Song,” the featured musical composition in the 1944 film classic, “Meet Me In St. Louis.”

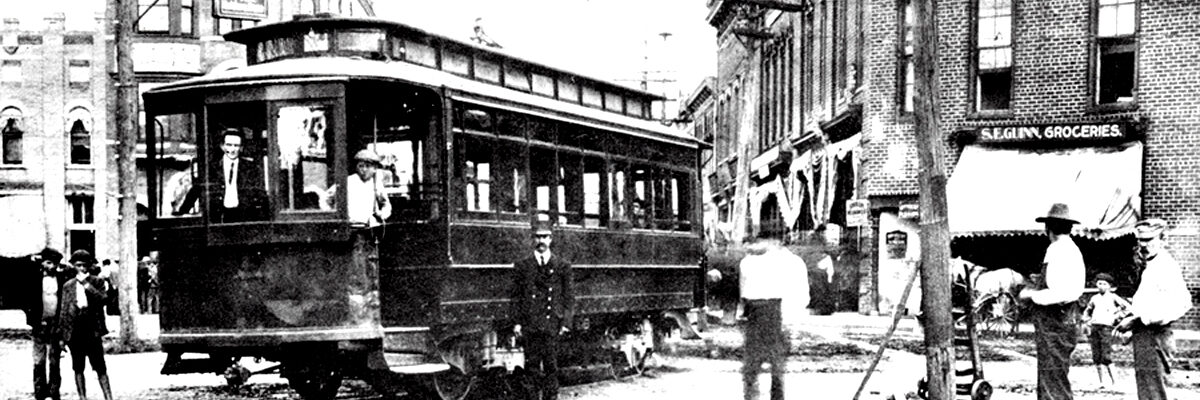

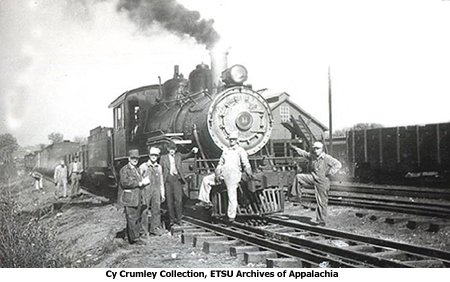

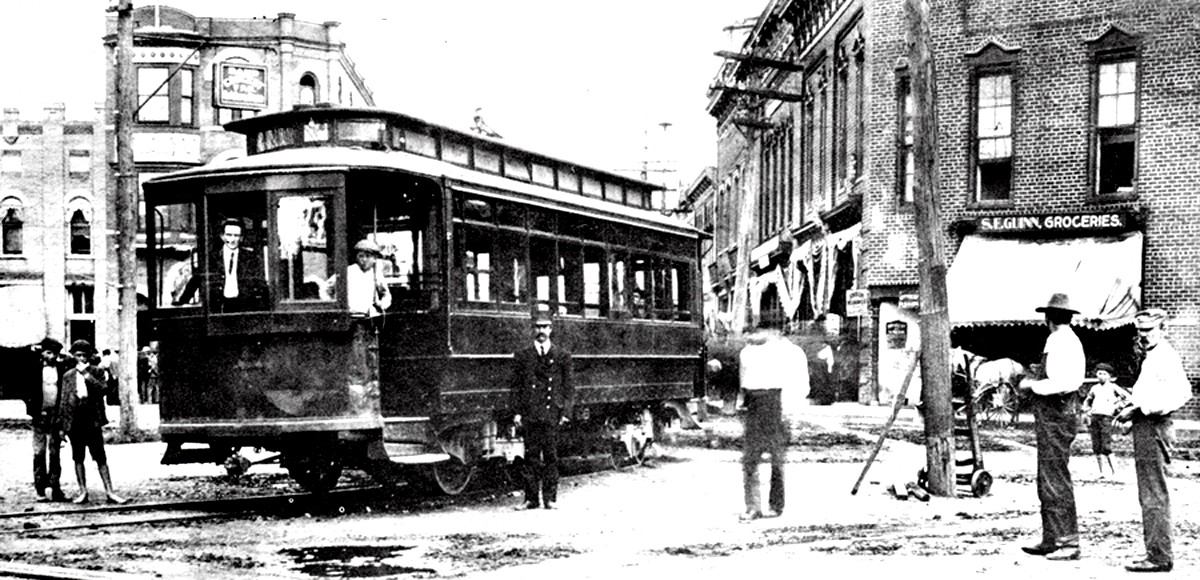

In 1887, the first successful electric street railway in the United States began operation in Richmond, Virginia. Five years later, the Johnson City and Carnegie Street Railway became a reality with a four-mile span of metal track. The trolley soon evolved as the city’s chief mode of travel, bridging the distance gap between inner-city dwellers and suburb inhabitants.

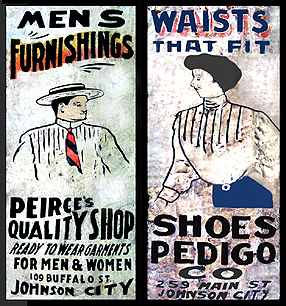

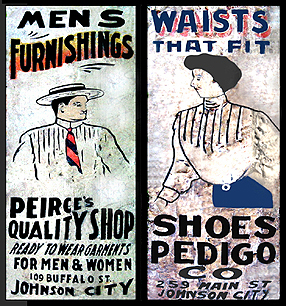

People in the outskirts of town could jump on the trolley and ride downtown to shop, watch a flick at a movie theatre, roller-skate at a local rink or attend a concert or lecture at Jobe’s Opera House. Likewise, urban residents could ride a streetcar to Lake Wataussee (later Cox’s Lake) for a fun day of boating, swimming and picnicking or stopover at spacious Soldier’s Home (now V.A. Center).

Trolleys permitted people to affordably commute to their work places. The Blondie newspaper comic strip often showed the always-late-for-work Dagwood Bumstead leaping desperately into the air to grab the trolley end pole just as the vehicle departed. Moreover, streetcars took people to school, church, the doctor, family gatherings, sporting contests and social events. The endearing little cars became a vital influence in the city.

The trolley barn was located at 100-102 N. Roan Street, former site of the Johnson City Power Board. The uniquely designed building contained ample space for storing streetcars that were not in service. After exiting the terminal onto Roan Street, the trolley driver had a choice of turning north to Carnegie Hotel and Lake Wataussee or south to the Normal School (later ETSU) and Soldiers Home.

Traveling south took the trolley to E. Main where it turned west and navigated to Fountain Square. Two route options emerged at this location; the trolley could go left onto Buffalo or continue west on Main. The Buffalo choice brought it to Walnut where it bore right and passed Model Mills (later General Mills). According to Ken Harrison, it turned left onto Southwest Avenue and then right onto W. Pine before arriving at the Normal School. The other Fountain Square route was to travel west on Main and eventually head south toward Soldier’s Home.

Leaving the trolley station and going north took it to Watauga where it proceeded east to a short passing section of two parallel tracks that provided a spot for trolleys going in opposite directions to pass. The trolley continued east to Oakland where it turned right and then left onto Fairview to the Carnegie Hotel. On weekends and special occasions, the company offered a trip north on Oakland and northwest toward Lake Wataussee.

Frank Tannewitz said it cost a nickel to ride the trolley. Many people walked rather than ride because a nickel was a lot of money in those days. A wire on top of the trolley connected it to the main power line. When the trolley got to the end of the line, the attendant switched the main supply wire from the front to the back to reverse the car’s direction. The attendant then flipped the seats over for the return trip.”

In my next column, I will relate how modern comfortable buses arrived in the city in 1931, causing the demise of the nostalgic little streetcars and silencing the familiar “clang, clang, clang” and “ding, ding, ding.”