Lynn Williams, former WBEJ chief engineer, recently reminisced about local radio stations in the 1930s and 1940s, including his affiliation with the Elizabethton station.

According to Lynn, “The first broadcast in the East Tennessee area was WOPI in Bristol on June 15, 1929. My family didn’t have a radio, electricity, or other things considered essential today. I first heard the station’s programming at a neighbor’s house in 1932, but it wasn’t until 1938 that my dad purchased a used Philco battery-powered floor model, exposing me to the world of radio.”

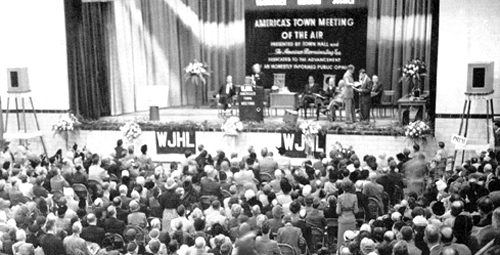

Lynn sent me a list of 248 radio affiliates that were transmitting about 1940. Seven cities and eleven stations in Tennessee were shown: Johnson City (WJHL), Bristol (WOPI), Kingsport (WKPT), Knoxville (WNOX, WBIR, WROL), Nashville (WSM), Chattanooga (WAPO) and Memphis (WREC, WMC, WMPS).

Many radio broadcasts in that era featured live programming. “Hillbilly” music became the rage with the populace after XERA, a powerful station located in Mexico just across the border from Laredo, began playing this musical genre all across the country by such old-time music groups as The Carter Family.

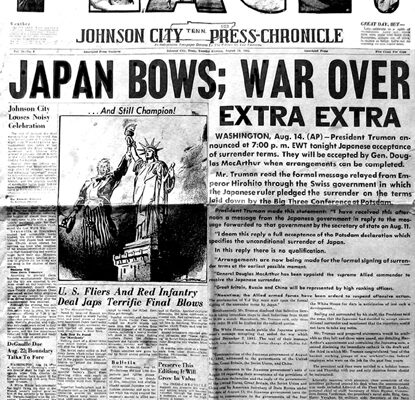

WBEJ entered the expanding market on the evening of July 18, 1946 with a special remote broadcast from the Franklin Club. A young Bill Hale was control board operator that night. Those present were station owners, Mr. R.W. Rounsavilleand George Clark, staffmembers and several well-known personalities from Elizabethton and adjoining areas. A new era for Northeast Tennessee dawned with that broadcast. Frank White (“The Old Guide”) and Bill Marrs (“Professor Kingfish”) proclaimed a decade later over WBEJ: “It was like a ten dollar rug; you couldn’t beat it.”

“For many years,” said Lynn, “groups of local musicians gathered at various places to “pick and grin.” My musical cousins and I performed locally that included performances on WJHL’s popular ‘Barrel of Fun’ program, initially broadcast from Kingsport and later at Elizabethton’s Bonnie Kate Theatre.”

Lynn recalled an important day in his life in 1946. He and a cousin were playing music on the front porch of his home at the corner and S. Main and Third streets. A young man whose name he cannot recall came walking across the Covered Bridge and stopped to listen to their music. He asked them if they would be interested in playing music for the new radio station being built in town when it became operational. They sent him back to the station with a resounding “yes” reply and promptly received an invitation for an audition. Someone suggested that they invite Paul Buckles to play with them and he too was receptive to the offer.

Buckles; his wife Aileen; T.N. Garland, a rayon plant coworker; Lynn’s cousin, Howard “Doc” Williams; the mystery lad; and Lynn assembled at Paul’s house on Elm Street to work up some numbers for their try-out.

Lynn further wrote, “We went to the WBEJ studio and ran through several numbers. Bill Lowery, the station director, was very impressed and asked us to come back in another week. Regrettably, the young lad was excluded from the invitation, but he accepted the news okay. We used the extra time by meeting several more occasions for practice. It was then that another person, Norman ‘Curley’ White, joined our band. He had been performing on the ‘Barrel of Fun’ show since it first aired.

“We went for our second WBEJ audition and this time the control room was crowded with people who were there to listen to us. When we finished, they rushed enthusiastically into one of two front studios. Lowery offered us the 6-7 a.m. weekday slot, but I told him that an hour was too much for one band to perform and that we would be repeating songs. I suggested that 15 minutes would be the desired length. He agreed. Although we received no pay from the new station, we were permitted to advertise our show dates.

“Bill asked us if we had a name. Some of us had been calling ourselves, The Green Valley Mountaineers, a name I thought of earlier. We changed it to The Green Valley Boys, although Aileen was obviously not a boy. We went on the air Friday morning, July 19, 1946 at 6:15 a.m. for 15-minutes.

“A WBEJ script detailed our introduction: ‘It’s the Green Valley Boys. (Theme). Good morning, good morning. It’s time for some friends of yours to drop over for a quarter hour visit. It’s Paul Buckles and the Green Valley Boys, featuring the Williams Brothers, Little Dolly and all the Green Valley Boys.’ (Theme). ‘And now, here he is, that man of the morning, Paul Buckles. Paul, good morning. (The announcer handles the show from here until conclusion with the exception of the spots. The band plays five selections.) (Theme). ‘Well, there they go, Paul Buckles and all the Green Valley Boys. They’ll all be back tomorrow, same time, same station and we hope you’ll be listening.’”

Three additional bands played that morning: Conley Smith and the Blue Springs Ramblers, Rondald ‘Runt’ Collins and the Stringtown Ramblers and Don Smith and the Melody Boys with Betty Hazlewood. Our announcer was usually Bill Huddleston. Curley White often featured songs made popular by Bob Wills and Tex Ritter.

“Eventually, a fifth group, Uncle ‘Dud’ and the Mountaineers, joined our early morning gang. They were very professional, having been a part of J.E. Mainer’s Mountaineers performing on radio for several months prior. Before WBEJ’s signing them on the air, they were working at WJHL. Their popular program could be heard in town by merely standing on Elk Avenue and listening to automobile radios as they passed by.

“On Saturday mornings, the WBEJ musical groups and others that were not on the radio assembled at the studio for a jamboree-type get-together that was hosted by Bill Lowery. There was also a Saturday night show that was broadcast for a while from the Tennessee Theatre in Johnson City. For orchestra music lovers, WBEJ provided a weekly program from the ballroom in the Lynnwood Hotel in Elizabethton across the street from the studio.”

Lynn’s experience playing old-time music for WBEJ led to a long and colorful career with the station beginning in 1948 when he was hired as a transmitter operator engineer. He left the station in 1983 when it changed ownership. Paul and Curley became announcers; Curley also became a well-known country deejay.