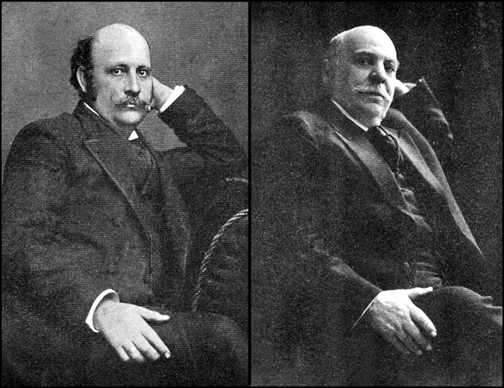

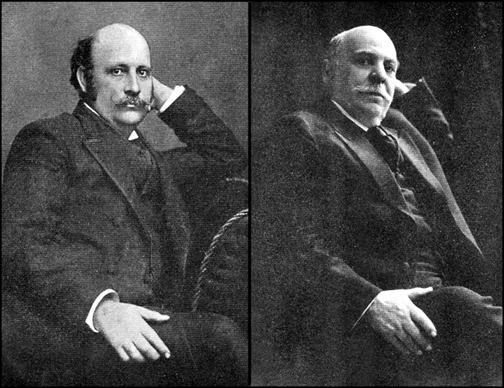

In October 1900, five nationally noted speakers participated in a lecture course at the Academy of Music for the Travelers’ Protective Association in Richmond, Virginia. Among those giving talks were East Tennessee’s homespun heroes, Bob and Alf Taylor.

Tickets were sold for each of five evening sessions. A $3.50 combination pass for all five sessions was the best deal with two admissions being offered to each event. An advertisement stated that although there had been an expected heavy demand for the course, some choice seats were still available.

Money collected went into a fund to compensate entertainers who would appear at the Academy the following year. The organizers took particular pride in the fact that they were offering the public a truly first-rate group of recognized talent who would command instant and hearty recognition from the attendees.

Hon. Alfred Taylor kicked off the series on Thursday, Oct. 11 with his celebrated “Life’s Poetry and Pearls,” a speech he had delivered in nearly a hundred cities around the South. He immediately offered his listeners a serious metaphor of human life: “There are heavens of poetry to which no imagination has ever soared; there are firmaments of beauty whose airs no wing has ever tried. Poets have sung since time began – painters, sculptors, and musicians have transferred their dreams to marble, and canvass, and harp strings, yet they have not so much as dipped an oar beneath the surface of that vast ocean of the beautiful whose silvery surf forever breaks on the shadowy shores of human life.”

Bob Taylor brought with him a brand new lecture that he titled, “Sentiment.” It was highly anticipated because attendees knew of Bob’s reputation for powers of pathos, word painting, anecdotes and mimicry: “(Sentiment) hangs a bow in every cloud and sets a star on every horizon. Its morning is a smile; its noon is a joy, its evening a tear. It sweeps the harp strings of human hearts and they thrill with every human passion.”

Bob further amused the crowd with a lighthearted tale: “An old poet of the flowing bowl (punch bowl) came down the village street one bright afternoon swearing he could climb a thorn tree a hundred feet high with a wildcat under each arm and never get a scratch. But the next morning he appeared with a bandage over one eye and a blue knot on his nose and his right arm in a sling. ‘Hello!’ shouted one of his pals. ‘I thought you could climb a thorn tree a hundred feet high and never get a scratch.’ ‘Yes,’ he said in a subdued tone, ‘but I got this comin’ down.’”

The other three presenters were Hon. George R. Wendling (well known in Richmond, speaking on the subject “Mirabeau and the French Revolution”), Dr. Homer T. Wilson (brilliant Texas natural born orator and humorist presenting a talk titled, “Sparks from the Anvil”) and Hon. Luther Manship (versatile, magnetic and amusing orator lecturing on “Dialects of the Nations”).

Twenty-one of the speeches that Bob and Alf delivered during their illustrious careers, including the two presented at the Association in 1900, can be read in their entirety in the book, Bob and Alf Taylor – Their Lives and Lectures (Paul Deresco Augsburg, Morristown Book Company, 1925). This is a fascinating work that demonstrates the verbal versatility of the famed brothers.

Two colorful local boys, who always had a warm spot in their hearts for their beloved “Happy Valley,” etched their mark in politics and music and made East Tennesseans especially proud of them. I am categorically one of them.