According to the late Ray Stahl’s book, A Beacon to Health Care, Johnson City’s first hospital opened in 1903 when the National Home for Disabled Soldiers became a reality. Four years later, Dr. W.J. Matthews opened a modest clinic on the first floor of the Carlisle Hotel (Franklin Apartments) at E. Main and Division streets. Then in 1911, six doctors launched Memorial Hospital, a small 10-bed facility at 712 Second Street (Myrtle Avenue).

With that said, a September 1915 edition of the Johnson City Staff newspaper contained an editorial from someone identified only as JOL, bemoaning the fact that Johnson City did not have a public hospital. Why did Mr. L say the city needed a hospital that year if Memorial Hospital was still in operation?

The editorial writer began his note saying, “I have been extremely interested in the new hospital movement since I had the pleasure of reading several articles by prominent local citizens in your good paper recently that I personally feel that too much cannot be said in behalf of this very much-needed institution.”

JOL noted that local doctors in 1915 were not wealthy enough to establish a private hospital or even collectively support one. To administer care beyond their capabilities, a patient had to be referred to a hospital in another city. That often meant traveling long distances over rough roads and incurring expensive medical bills. Local doctors were strapped for lack of modern equipment, medical support and hygienic facilities.

Emergencies were another matter. With time being of essence, local doctors frequently took extraordinary measures to save lives and provide relief for their patients. To ease the burden on the doctors, the writer felt that Johnson City deserved a modern hospital. The need became even more critical after automobile and railway traffic significantly increased. Also, industry growth bringing with it new and sometimes hazardous occupations necessitated a quality medical center.

On the financial side, few hospitals were moneymaking institutions with practically all of them being supported through endowments and subscriptions. Local doctors made it abundantly clear that they did not expect to use the hospital for moneymaking purposes. It was to be an institution for the care of patients. They reasoned that with a new hospital, they could refer people needing medical attention to it rather than sending them outside the city, thereby saving them time, money and possibly their lives.

The new hospital movement required modern facilities with an X-ray machine, a thoroughly equipped and sterile operating room, an ambulance and congenial surroundings. Charity patients would not be turned away; the hospital would be open to everyone, rich or poor.

JOL concluded his editorial with a challenge: “Every good citizen should manifest some interest in this very worthy institution.”

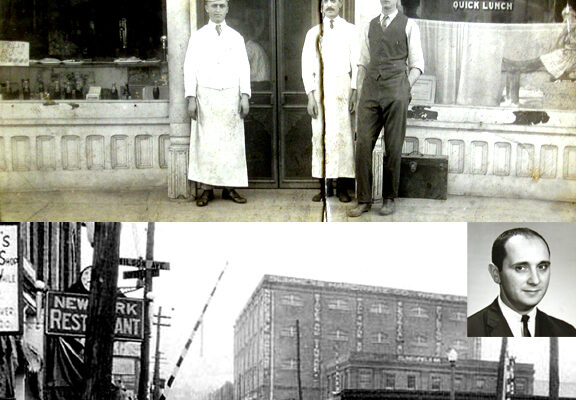

New Appalachian Hospital at Seventh (Chilhowie) Avenue

Apparently the overly crowded and inadequate Memorial Hospital in 1915 did not meet the standards of a “new hospital movement,” prompting JOL’s editorial. Five businessmen quickly remedied the situation when they purchased Cy Lyle’s (The Comet newspaper’s editor/publisher) 2-story, 16-room brick house at 809 Seventh (Chilhowie) Avenue for the new Appalachian Hospital. The group previously secured a charter that granted them “the right to organize, equip, own and operate a hospital and sanitarium.”

The facility opened to an appreciative public that likely included Mr. JOL. From that modest medical beginning of yesteryear emerged today’s impressive Johnson City Medical Center. … and the beat goes on.

-648x400.jpg)