The recent firing of Derek Dooley as head football coach at the University of Tennessee brought to mind another gridiron coach from the college’s yesteryear.

On January 24, 1951, the University of Tennessee gave 58-year-old football coach, General Robert Reece Neyland, a lifetime contract after his team won 10 games that season, lost one to Mississippi State and upset Texas 20-14 in the Cotton Bowl. Tennessee scored 315 points to their opponents’ 57, placing the Vols fourth in the country in the final Associated Press poll.

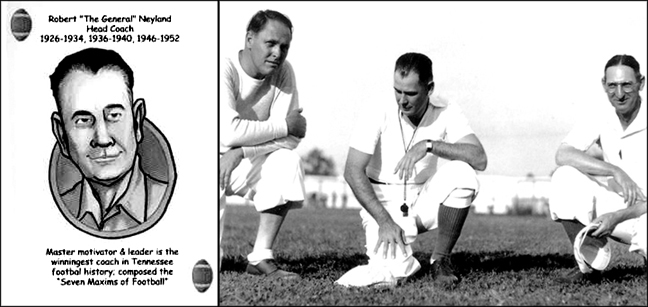

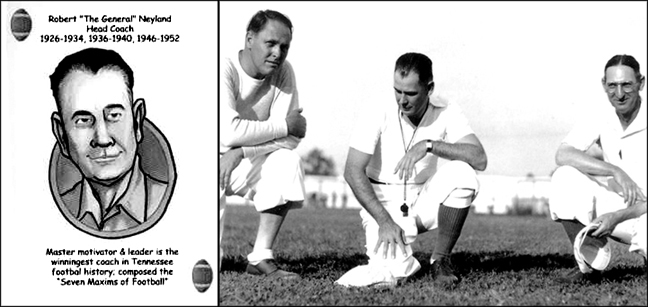

Robert Neyland Playing Card; Bill Britton, Neyland, Paul Parker

Although Neyland's annual salary was not made public, speculation placed the figure at $16,500 plus an additional $2,500 for expenses, making him one of collegiate football’s highest paid coaches. He was a disciple of the old single-wing formation.

In announcing the extension of the coach’s contract, Nathan Dougherty, chairman of the Athletic Council, said, “Our agreement with General Neyland ensures that he will remain at Tennessee for the remainder of his athletic career.” The coach responded, “I'm very happy to remain at Tennessee because I’ve always wanted to stay here.”

Neyland came to Tennessee from West Point in 1925 as a military science instructor and assistant football coach, becoming an overnight success. His Volunteers won eight games and lost one that year. In the next six years, Tennessee won 51 games, lost one and tied five. Neyland's overall record in 19 campaigns was 154 wins, 24 losses and 11 ties. Skillful blocking and tackling became trademarks under Neyland’s balanced single-wing system.

As a major in the Army engineers, Neyland went to the Panama Canal Zone in 1935. Although he retired the next year and returned to Tennessee, the Army summoned him back to active duty in May 1941. He served a five-year stretch, retiring with the rank of general.

In 1951, it was common knowledge that the general wanted one more outstanding season before he quit active coaching and relegate himself upstairs at Tennessee. That desire was to include an unbeaten and untied season plus a bowl game victory, allowing him to invoke the lifetime clause of his contract and retire as athletic director and advisory coach. Neyland, then 59, had accomplished this only once during his 21 seasons at Tennessee. That occurred in 1938, when the Vols dumped 10 regular season opponents, yielding only 16 points while piling up 276 and then trimming Oklahoma in the Orange Bowl 17-0.

Tennessee went on to beat Texas in the 1951 Cotton Bowl 20-14, but lost in the Rose Bowl, twice in the Sugar Bowl and again in the Orange Bowl. Neyland made it known that he was ready to retire from the sport.

In 1952, the general, who lived modestly on an income reported to be $25,000 a year, owned a $200,000 plus home at Sarasota, Fla., where he fished after every football season. He made no bones about wanting to retire within a few years. Neyland's mantle as head coach was expected to transfer to balding Harvey Robinson, his offensive coach and Tennessee quarterback in the 1930s.

Whenever a longhaired musician hit town, Robinson, an accomplished pianist, was present as an enthralled spectator. Neyland, famous for his “bull” victory roars, was strictly from the big band era of Vaughn Monroe and Spike Jones. Robinson was more communicative than the general. Neyland shunned publicity, never appeared on television or radio and granted only a few cautious interviews. He vehemently rejected all offers for ghostwritten articles bearing his signature.

Neyland’s coaching finale occurred after the 1952 season. On advice of his doctor, he asked the university to relieve him of his coaching duties, which they did. He remained as athletic director. As expected, Harvey Robinson got the nod to become Tennessee’s new coach. The 70-year old general died on March 28, 1962. Today, the stadium and road behind it proudly bears his name.