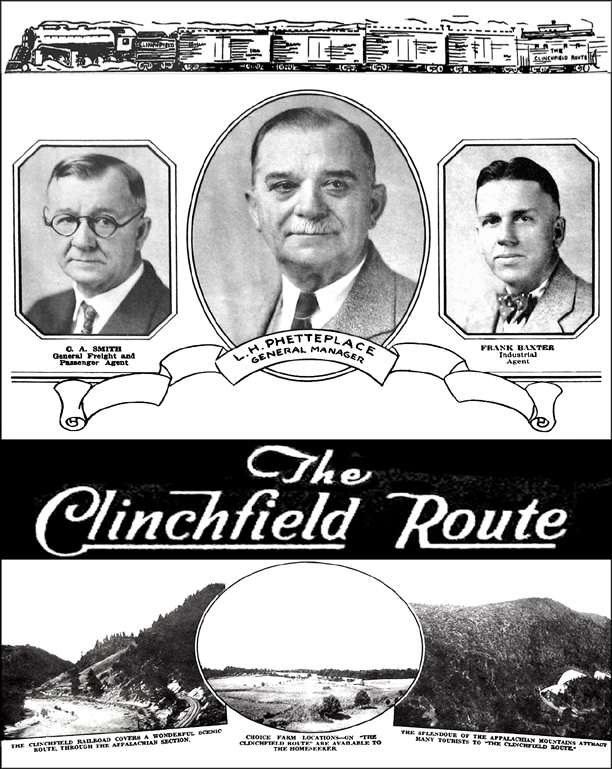

An April 1939 article in the Johnson City Chronicle and Staff News provides specifics of the building of a new and difficult train route across the Blue Ridge Mountains. The title was “The Building of ‘The Clinchfield Route’ – A Romance in Railroad Construction.”

A dream that had fostered in the minds of enterprising individuals from the earliest days of railroad history was the completion of a railroad that would span from the inland countryside across a portion of the vast Appalachian Mountains to the seacoast.

In 1832, John C. Calhoun (South Carolina politician, 7thVice President of the United States) advocated the building of a road from Charleston, South Carolina to Cincinnati, Ohio. In 1836, a company was formed for this purpose. Robert Y. Hayne (another South Carolinian, debated Daniel Webster of Massachusetts) became president of the road. Surveys were made and construction began on the South Carolina portion of the line. John C. Fremont (first republican candidate for the Presidency) was employed as a surveyor.

Over the years, numerous schemes for building a railroad on a direct route from Charleston to Cincinnati were considered but never pursued because of overwhelming mountain barriers. The plan lay dormant until about 1887 when General John T. Wilder (Union Army soldier, Carnegie developer, Cloudland Hotel builder) interested capitalists in the construction of the road. It was named the Charleston, Cincinnati and Chicago (3C) Railway. Success in the ambitious undertaking required a heavy dose of courage, capability and cash.

Several English capitalists backed Wilder’s vision, spending about seven million dollars. However, they were forced to suspend work in 1893 when one company, Baring Brothers (English bankers), went bankrupt. The road underwent foreclosure proceedings and was sold to Charles E. Hellier on July 17, 1893. He reorganized it as the Ohio River and Charleston Railway Company. Two months later, the new company extended the road from Chestoa, Tennessee to five miles south of Huntdale, NC, a distance of about 20 miles.

In 1902, George L. Carter (rail and coal magnate, founder of modern Kingsport) and associates purchased the property of the Ohio River and Charleston Railway Company and formed the South and Western Railway Company with the idea of developing the coalfields of Southwest Virginia and Eastern Kentucky. They acquired large tracts of coal lands in what has since become known as the “Clinchfield Section.”

The New York “money kings” were initially reluctant to invest in the risky venture. After Mr. Carter acquired additional surveys and reports, Thomas F. Ryan formed a syndicate to build the road. For four years, money was shoveled into the rocky fastnesses of the Blue Ridge Mountains for the purpose of boring hills and bridging valleys. Difficult sections of the mountains were tackled first leaving easier ones to be surveyed and left undisturbed until later.

The company next extended the North Carolina portion of the line from Huntdale to Spruce Pine. Additional work was halted until 1905 when Mr. Carter interested John B. Dennis and Blair and Company of New York in the venture. Dennis is credited as being the principal force behind “The Clinchfield Route.”

That same year, extension of the road from Spruce Pine, to the south and Johnson City to the north began. Although the general plan of the old 3C road was followed as much as practical, new surveys provided more gentle curves and lower grades. In 1909, the road was completed from Dante, Virginia to Spartanburg, South Carolina. Further progress was made between 1912 and 1915 when it was extended north from Dante to Elkhorn City, Kentucky, a distance of about 35 miles.

The 309-mile stretch crossed four distinct watersheds and required 55 tunnels, which were built to a standard of 18 feet wide and 22 feet high. The shortest length was 179 feet and the longest one was 7854. Cost was high with one passageway totaling $500,000 and several miles of mountain road chalking up a price tag of $200,000 a mile. Elkhorn City was 795 feet above sea level while Spartanburg was 742. The highest point of the entire track measured 2628 feet at the crest of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

The maximum grade of one-half of one percent was strictly enforced along the road. At times, construction work was halted after it was determined that a section of road would not achieve the required grade restriction. Lower grades were ideal for larger locomotives such as Mallet and Mikado that typically pulled 80 to 100 cars of coal.

The height above sea level of The Clinchfield Route was said to be the greatest in the east and its stunning scenery was hardly surpassed anywhere in the world. While other roads had dodged severe mountain barriers, the Clinchfield boldly cut through them. Throughout almost its entire length, it traversed rugged mountain country with an impressive high standard of construction.

On October 29, 1909, Spartanburg residents celebrated the opening of the much-anticipated line. They deemed the CC&O as “one of the greatest little railroads in the United States.” During the festivities, two individuals, H.H. Rogers and Thomas F. Ryan, were singled out for their efforts in making the road a success. The completion of the Clinchfield Route satisfied the yearnings of early statesmen by successfully opening a section of country that was abundantly rich in natural resources.

When the economic depression occurred in 1910-11, much construction work across the country was suspended except for two significant endeavors – the Panama Canal and the CC&O Railroad. The country was determined to finish what it had begun – digging a canal and finishing a railroad. Both were completed.

Comments are closed.