In 1929, Helen Jackson, a former resident of the Southern mountains and a current resident of Brooklyn, NY, had cautious words to describe the Southerners she loved so much. They supplied her business with high quality pedigreed mountain pottery: “I love my mountain people,” she said, “and I don't want to call them illiterate. They just haven't had the advantage of an education.”

Jackson routinely traveled to the Unaka Mountains and returned with ware for her New York business. The majority of it was used to make lamp bases with parchment shades that she designed herself.

This mountain range, along the Tennessee-North Carolina border, supplied fine clay for the potters whose work sheds were dotted in all directions throughout the region that she had known since childhood. She, like the other children of the region, always took great delight in watching her talented neighbors at work.

“My lamps are pedigreed lamps,” she explained, ''They're made of the same clay that was used by the famous Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, a firm known for making highly prized ware. I even have the log made by the Wedgwood firm that was sent to America from England in 1767.”

The rich veins of clay in those mountains had been known to the Cherokee Indians, who inhabited the region years before any white settlers arrived. The Indians made use of it for their own purposes and when the first white colonists arrived, they quickly learned of the presence of this superior clay. The fame of their products spread not only throughout the colonies but also to England, with the result that Wedgwood sent representatives to America to obtain five tons of the prized clay.

English potters migrated to the new clay fields and the inhabitants of the district were the descendants of those early settlers. They used the same primitive method that their ancestors relied upon, such as weighing out clay by using a bucket of stone for a weight.

The ancient kick-wheel of centuries past was still the preferred choice of mountaineer potters and each piece was burned in wood-fired kilns. “My potters don't want new methods,” declared Mrs. Jackson. “They say that power-wheels would spoil their product because they shape a vase as much with their feet as with their hands, feeling their product as they made it. It is this individual attention to each piece that gives this unique pottery its own particular charm. Each article is different from the rest.”

Many shapes such as “Bible” pitchers were made by the potters when Mrs. Jackson first began studying their work. Many of the shapes were evidently traditional, having continually been handed down from parent to offspring.

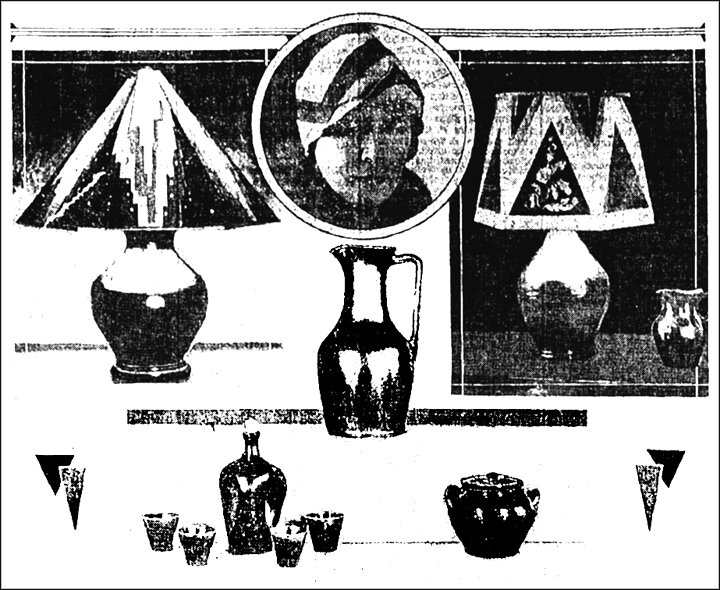

Helen Jackson Displays Her Unaka Mountain Pottery Products in 1929

The colors of the vases were particularly delightful because no kiln full of pottery ever came out the same; each vase took on different coloring, depending on its nearness to the open flame. From the same firing, one vase would emerge as bright red, another streaked with brown and a third having dark red with green shadings. The possibilities were beautifully endless.

Mrs. Jackson carefully named all her lamps. “The Widow” was a dark, metallic vase with a shade of black and gray. “The Cedars” came out red, yellow and green-white, showing slim evergreens pointing upward on the shade. Many of her designs were taken from the subtle effects in pieces of chintz (glazed calico textiles) she had chosen.

“The Fountain,” in red and cream, displayed a red vase with a creamy shade, each panel showing a spraying fountain. Mrs. Jackson had some huge porch vases that stood several feet high, beverage bottles with pinched in sides that made them easy to handle, cups to match, corncob stoppers, lovely long-necked pitchers, flower vases and a dazzling variety of sizes and shapes in lamps.”

Mrs. Jackson concluded by saying: “I have the added advantage of being adaptable for seasonable usage. There were autumn colors, those suggestive of winter holidays and others reminiscent of summer's glory.”

Comments are closed.