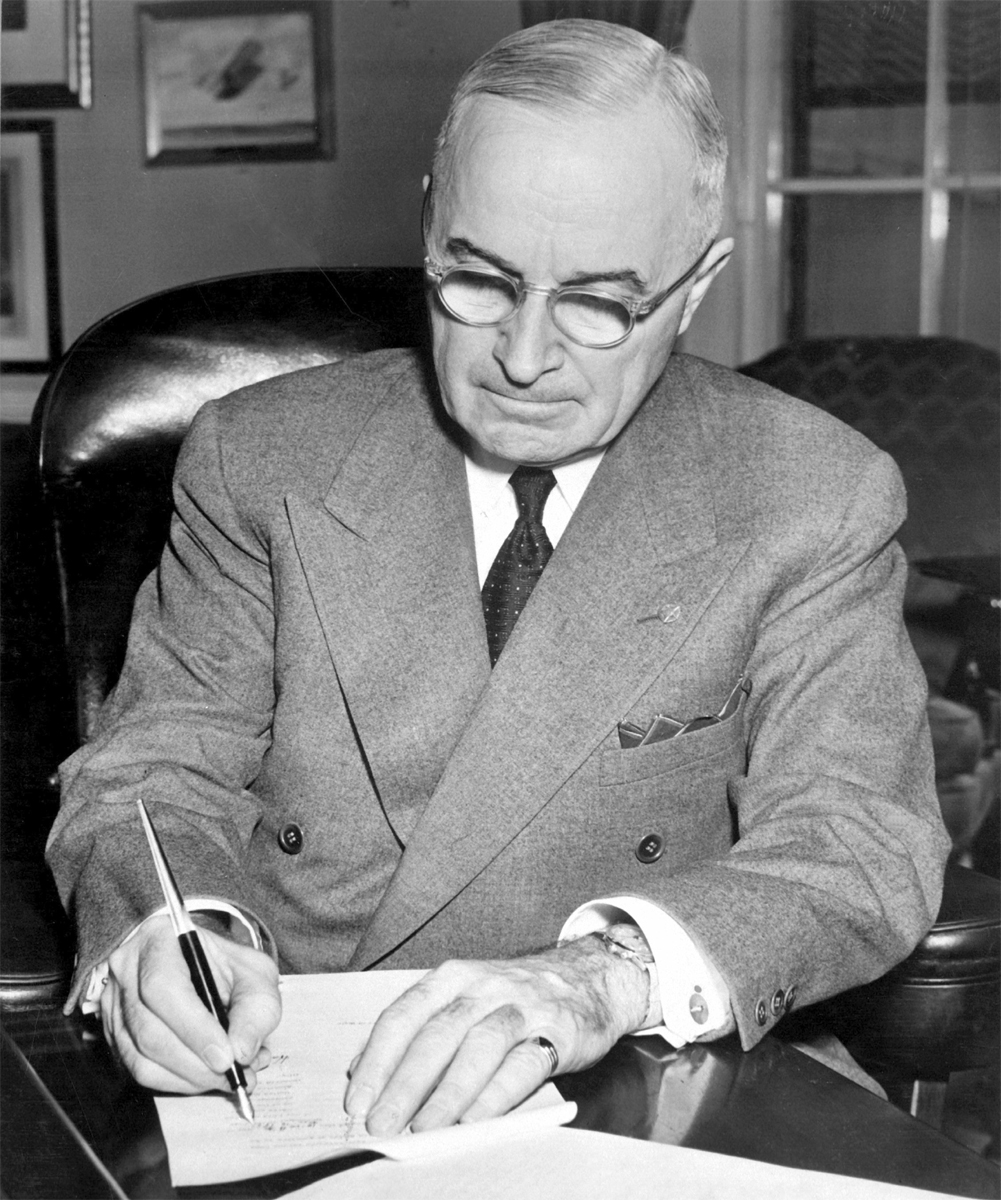

On Christmas day, 1951, President Truman told the nation that there had arisen a new spirit of hope in the world, that a true and lasting peace may come from the sacrifice of free men arming and fighting together. Mr. Truman's message was prepared for broadcasting from his fireside at Independence, MO., just before he pressed a telegraph key and set the nation's Christmas tree aglow with colored lights at the White House.

The president harked back to when the nation found itself fighting for survival in the most terrible of world wars. “The world is still in danger tonight,” he said, “but a great change has come about. A new spirit has been born and has grown up in the world.

“Tonight, we have a different goal and a higher hope. Despite difficulties, the free nations of the world have drawn together solidly for a great purpose, not solely to defend themselves, not merely to win a bloody war if it should come, but for the purpose of creating a real peace, a peace that shall be a positive reality and not an empty hope but a just and lasting peace.

The president spoke in moving terms of the men on the Korean battlefields that Christmas Eve and of the loneliness of those who waited for them at home.

“We miss our boys and girls who are out there,” he said. They are protecting us and all free men from aggression. They are diligently trying to prevent another world war. We honor them for the great job they are doing. We pray to the Prince of Peace for their success and safety.”

Mr. Truman said the Korea conflict is unique in history in that the free nations are proving that man is free and must remain free, that aggression must end, that nations must obey the law.

The victory we seek is that of peace; that victory is promised to us. It was promised to us long ago, in the words of the angel choir that sang over Bethlehem, “Glory in the Highest, and on Earth, Peace, Good Will Toward Men.”

On another note, that same year found Christmas pilgrims from 30 countries assembled in freezing cold, rallying in Bethlehem. They were there to celebrate the holiday on the spot where Christ was born.

Bone-chilling cold, which marked the Holy Land's worst Christmas, weather wise, failed to stop the annual pilgrimage.

More that 2,500 persons passed barbed wire barriers through Jerusalem, across the Mount of Olives to Bethany and then to the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem.

There were priests in colorful robes that were assembled to honor the birth of Christ with ancient rites.

That pilgrimage, like the shepherds and the three wise men, many years prior found in Bethlehem a town of dome-roofed houses and narrow crooked streets.

The sun broke through a hazy overcast on Christmas Eve for the first time in 10 days and the women of Bethlehem devoted most of the morning to hanging out washings.

Pilgrims that year found Bethlehem's population doubled from it former figure of about 12,000. The increase was caused by an influx of Arab refugees from Israel, many whom lived in caves and rain-soaked tents on the outskirts of the town, which was situated in the Arab territory of Jordan.

Hostilities ceased between Israel and Jordan, but there was still a technical state of war. Only by special arrangement were Israeli Christian Pilgrims permitted to make the traditional journey to Bethlehem.

Friends shouted a Christmas greeting across the barbed wire barriers, waiting impatiently to be cleared by the blue-clad Israeli police and the Khadi-clad soldiers of Jordan's Arab Legion.