The Appalachian Trail is a 2,168-mile (2001) footpath for walkers. (According to a 1931 newspaper, it was originally planned for 1200 miles, but has been enlarged over time because of numerous modifications and rerouting.)

The massive, impressive project passes through 14 states: Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine. Perhaps the best definition of the hikers' dream comes from the Appalachian Trial Conference that organized in 1931:

“The trail is a route, continuous from Mount Katahdin in Maine to Springer Mountain in Georgia, for travel on foot through wild, scenic, wooded, pastoral and culturally significant lands of the Appalachian Mountains. It is a means of sojourning among these lands so that visitors may experience them by their own unaided efforts.

“In practice, the trail is usually a simple footpath, purposeful in direction and concept, favoring the heights of land and located for minimum reliance on construction for protecting the resources.”

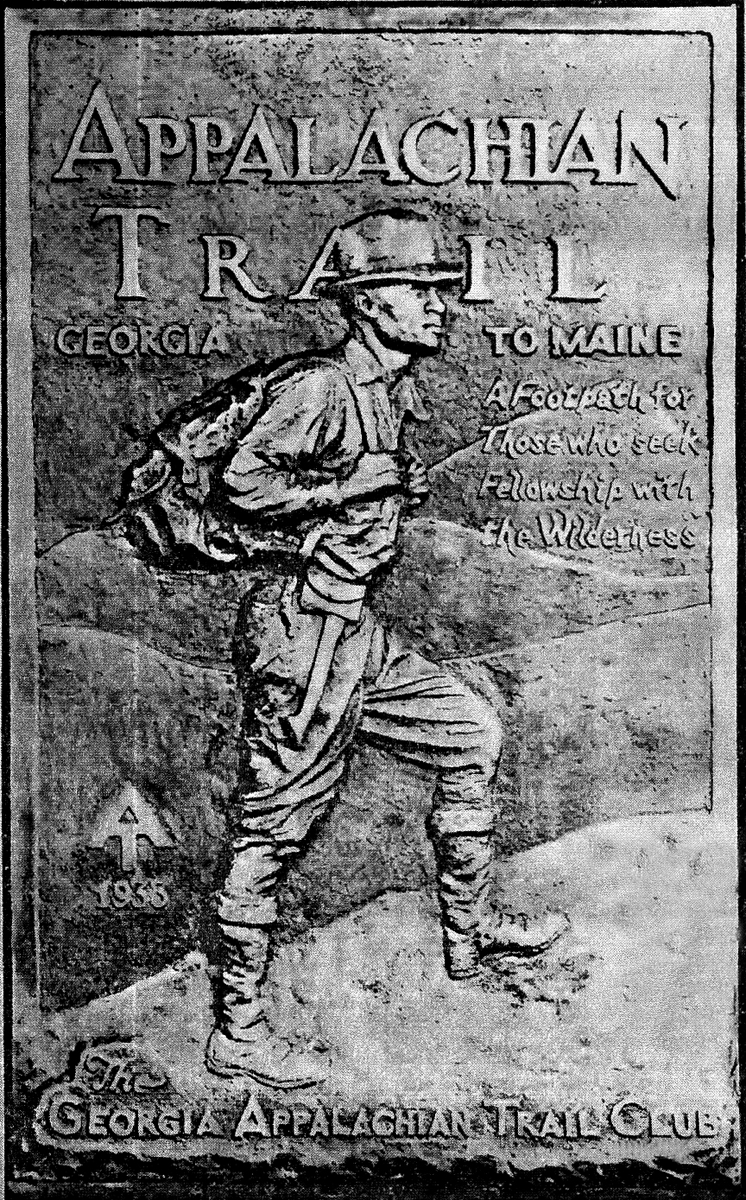

Booklet Cover from the Appalachian Trail Club

The trail was provided by the lands it traversed and its survival depended on the living stewardship of its volunteers and workers along the Appalachian Trail communities.

The construction of it alongside the Appalachian summits and ridges, began in 1922 in the Bear Mountain and Harriman sections of the Palisades Interstate Park of New York and New Jersey. It was reported to be more than half finished at the fifth annual Appalachian Trail Conference held at Gatlinburg (“The Burg”), Tennessee at the western gateway of the new Smoky Mountain National Park.

The Appalachian Trail project was proposed in 1921 as an extension of regional planning for wilderness recreation through the American Institute of Architects. They seized upon the imagination of members of hearty volunteer support to a degree, which made it one of the most remarkable recreation projects of that time.

Major W.A. Welch, is credited for designing the trail's metal markers with the impressive legend, “Appalachian Trial – Main to Georgia,” which became the emblem of the enterprise.

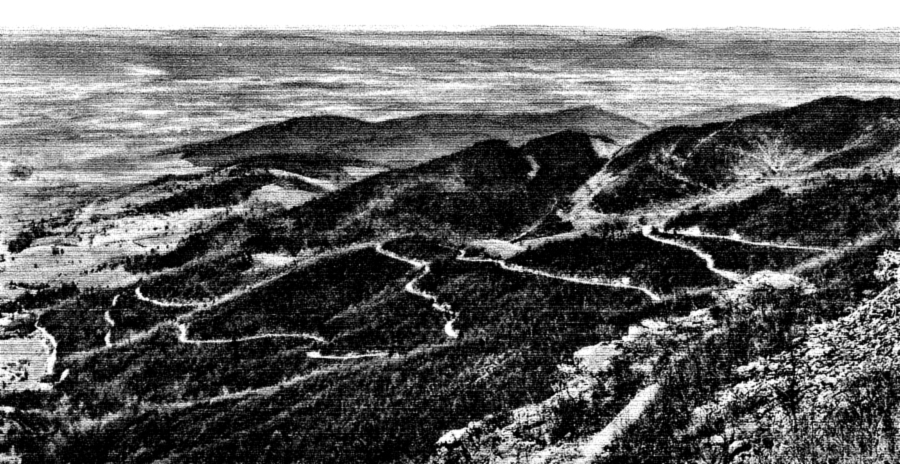

Appalachian Trail from Franklin Cliffs, Skyland Drive, Virginia

Extension of the Appalachian Trail in various separated portions made necessary a standard marker that could be recognized everywhere. Therefore, Welch changed the legend on the first markers from Palisades Interstate Park Section to “Maine to Georgia,” which was then used all along the way in most of the 14 states through which the trail passed.

Cumulative increase in interest in the following two years led to many new developments and additional groups eager to join in and do their fair share of work. The enthusiasm allowed the trail to be completely marked within the next five years, a remarkable achievement considering the roughness and remoteness of many parts of the terrains over which the trail passed. This was especially true across Northern Maine and in the mountains of North Carolina, Tennessee and Georgia.

Besides interest shown by outdoor clubs, the effort was supported by many public agencies and officials, including the Nation Forest Service, state parks and forest commissions, Boy Scout Councils and others. Interest was spreading like wildfire.

The significance of the great trail was envisioned as a spinal cord for wilderness recreation paths in the eastern mountain areas. It stimulated the enthusiasm of all who enlisted in the work with each passing year.

Appalachian Trail Brass Challenge Coin

The 1931 meeting was held in the South in recognition of the impressive development in the project that had occurred there during the previous year and to stipulate it further. It was under the auspices of the Smoky Mountain Hiking Club of Knoxville, Tennessee, of which Prof. H.M. Jennison of the department of Botany, University of Tennessee, was president.

The construction of the Appalachian Trail in the Great Smoky Mountains area was expected to be furthered by the impending development of the new and exciting National Park therein. Timing could not have been more convenient for both momentous ventures.

The Smoky Mountains Hiking Club marked the route into more accessible sections. Crossing Indian Gap, the park forces were helpful in making and maintaining it into the more rugged and remote portions in the northern part of the area still being acquired for eventual addition to the Park.

The supervisors of the Unaka National Forest, extending from the Virginia border into North Carolina and the Cherokee Forest in Western North Carolina and Southern Tennessee, were helpful by designating and marking miles of the Appalachian Trail. The newly formed Carolina Appalachian Trail Club of Asheville, North Carolina was likewise active in the Smoky Mountains.

In Virginia, a new and energetic group, the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club accomplished an immense amount of work along with the Virginia Blue Ridge from Harper's Ferry to the Shenandoah National Park area and beyond.

Appalachian Trail Patch

In Georgia, the state Forestry Department had been co-operative and one of its assistant foresters had formed the Georgia Appalachian Trail Club, which had marked the trail from its southern terminus at Mount Oglethorpe, northward to the Tennessee line.

Important developments from New England were also reported at the Gatlinburg meeting. A promising amount of literature began to develop as informative guides to the Appalachian Trail became available to the public. The Potomac Appalachian Trail Club also published a map to the Virginia section.

Thanks to the efforts of all the individuals and organizations in this article, the Appalachian Trial, a hikers' wildest dream, became a reality and is still with us today.