My January 9 column concerning the retirement of former Johnson City School Superintendent, C.E. Rogers, prompted a letter from Ms. Pat Willard, who commented about several of the people mentioned in the article.

“I knew who Mr. Rogers was,” said Ms. Willard, “because his wife was in charge of the nursery school I attended as a young child during World War II. It was for children whose mothers were helping with the war effort by entering the work force. My mom worked at Dosser's Department Store selling yard goods. Every woman in the work force freed a man to go into the military.”

“Mrs. Rogers must have taken a special interest in me. One evening, my parents and I walked from our home in the 300 block of Poplar to the Rogers home on Maple in the block next to the college. They had arranged for me to attend Training School (University School) when I began school in the fall, but my parents left the decision to me. I chose to go to South Side School.”

“I am sure that Miss Nancy Beard of your article was the principal of South Side. There was a story that her favorite song was ‘Let it Snow’.”

Pat mentioned Edith Keyes, the part-time librarian at South Side who only worked in the afternoons around 1946. She encountered her again in the late 1990s as a member of the Monday Club and the Institute of Continuing Learning. Miss Keyes had a reserved parking space at the college. Some mornings when she arrived for work, she would find a car parked in her space. She would return home to Jonesboro (Jonesborough), call the college and tell them that she would be in to work when her parking space became available. Pat acknowledged that this could have been a tall tale.

I noted in my column that Mrs. Orville Martin was my occupations teacher in Junior High School. Pat also had her for the same subject. When she turned in a career book to her teacher, Mrs. Martin refused to let her be an architect or a dog breeder in the course, instead urging her to choose nursing. She complied and passed the class.

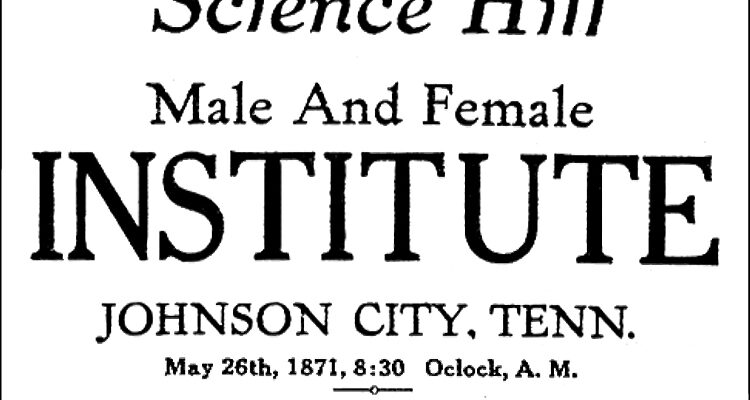

When Ms. Willard was in her senior year at Science Hill High School, her mother urged her to pursue civil engineering as a career. No one supported or objected to her decision. During the last semester of her senior year, she exchanged typing for mechanical drawing. The principal, George Greenwell, approved her taking the class, making her the only girl in the class. Mrs. Martin learned of her decision and sent word how proud she was of her. Pat studied civil engineering in college.

Ms. Willard mentioned Elise Lindsey whom she believed resided in the 100 block of West Poplar. Her father ran a gas station on South Roan. Pat believed that she likely taught at Columbus Powell.

Pat identified Margaret Woodruff as an elementary school principal. She surmised that she held the position at Stratton Elementary School on Oakland Avenue. She was also one of the three daughters of J.D. and M. E. Woodruff who built a house in the tree streets section of Johnson City in 1906. Mr. Woodruff was a timber agent. She noted that the house was still unpainted with natural chestnut woodwork in most of its many rooms. The family reared eight children in that house before Mrs. Woodruff, a widow by then, sold the property to Pat’s father in l951. The family moved to a large red brick house in the 200 block of Locust Street.

Although Pat did not know School Superintendent C. Howard McCorkle, she knew who he was. She remembered Mrs. Starrett as a very stately woman who taught music in the area.

Pat concluded by saying, “You mentioned others whose names are familiar to me but about whom I have no definite memories. This was great fun. This was a nice little walk down memory lane.”

-504x400.jpg)