Few things are more nostalgic than the thought of an old schoolhouse with its resounding bell, tin ceilings, rough-hewn wood floors, black potbellied stove, desks with inkwells and slate blackboards. The rope or hand-operated bell’s toll echoed across the vast countryside each weekday, beckoning youngsters to and from school.

A 1912 poem, “Song of the School Bell,” by John Everett says: “Each day at nine are loudly sung, Clear greetings from my iron tongue, While children rush with romp and race, As though to meet my fond embrace.” This device’s distinctive wistful sound caused scurrying little feet to react each time it interrupted the silence. Community schools served the learning needs of rural children until farms grew larger and families became fewer.

When my great grandfather, Samuel Bowman, died in 1905, his obituary notice acknowledged that he once attended Swadley's Schoolhouse and “obtained what, at that time, was a fair education.” Not being familiar with this center of learning, I found reference to it in a 1969 Johnson City Press-Chronicle article by the late Dorothy Hamill.

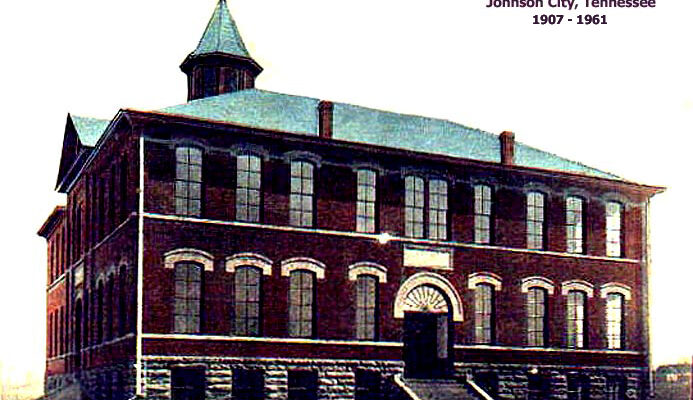

The original school was built about 1870 by Henry Swadley on land along Oakland Avenue near the base of Master Knob. Noah Sherfey was principal and teacher; he was also a local minister. Four years later, a larger building, carrying the identical name, was erected on land just a few yards from the former school.

About this same time, Pastor Sherfey purchaseda hand-operated bell for the new facility. Noah’s son, Paul Sherfey, later inherited the bell from his father, describing it as being slightly larger than 4×7 inches. The solid brass bell, according to Sherfey, had a distinct tone, was clear, loud and commanding; it could be heard across a fairly wide vicinity.

During the 1875-76 school year, students in the advanced history class were engaged in a study about Princeton University in New Jersey. The youngsters were so engrossed by the Ivy League institution’s name that they successfully convinced school officials to change the name of their school to Princeton School.

Noah taught at the newly named school for two years and then became employed at Union School on the Bristol Highway. The educator returned to his former institution about a year later. Sherfey served at Union School for another stint, eventually becoming a teacher in Sullivan County until shortly before his death in 1918.

Paul acquired the program for the closing of school in 1879, written in his father’s handwriting. The ceremony began with music, an address of welcome and a series of declamations and recitations by students. Mrs. Leighton wrote and read an essay on “The Beauties of Nature” and J.W. Scalf made a presentation on Indians. Another interesting relic was an 1883 contract for Noah to teach penmanship at Princeton during a 10-day summer period. The agreed upon pay was one dollar.

Paul Sherfey also inherited a collection of 13 pens from his father; some had broad, flat, serrated points and were termed shading pens, being of varying widths. An additional possession was a speech written by the senior Sherfey and delivered before a group of educators asking for “Uniformity of Textbooks.”

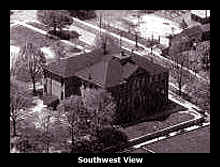

Although the old school bell’s metallic tongue no longer articulates for the students, the old building continues in service today as Princeton Arts Center.