On October 6, 1928, newspapers around the country proclaimed that the picturesque little mountain city of Elizabethton, Tennessee would play host to presidential hopeful, Herbert Hoover.

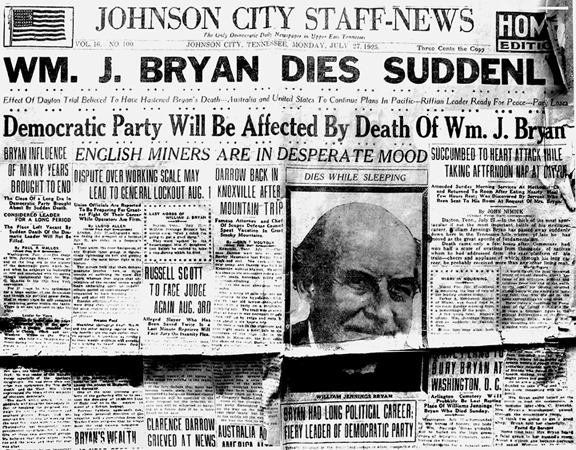

Herbert Hoover became the 31st president of the United States in 1929 largely because of his favorable national reputation, a booming economy and deep splits within the Democratic Party. The future president, well satisfied with the political outlook and the functioning of the machine he built to carry the Republican message to the country, which included a strategy to target Southern states.

In the fall of that year, Hoover traveled to the Southland to make his fourth major address of the campaign—a personal appeal to the voters of Democratic Dixie to support his Republican candidacy.

After leaving national headquarters in the nation's capitol, the nominee traveled down the Valley of Virginia to Bristol, Virginia where he made an impromptu address to the crowd that had gathered at the station. Republican leaders of Virginia were invited to join the party.

(Clockwise: Hoover campaign poster, vote for Hoover Sticker, comedic policitcal birthday card, American Glanzstoff (North American Rayon) and Elizabethton courthouse and monument downtown)

When Mr. Hoover arrived at 10 a.m. at the flag station of Childers, located four miles away, he was greeted by a large motorcade of specially decorated cars. During his drive to the city, he passed through a crowd of 7,000 school children who tossed flowers in his path. After traveling the principal streets of the town, the entourage guests were hosted to a luncheon provided by the Chamber of Commerce.

Politics was essentially set aside as Democrats joined hands with Republicans. Even the Al Smith Club that had recently organized suspended activities until after Hoover's departure. The event was described as a “great show” that attracted those who had never visited Elizabethton, or for that matter, had never heard of the town. Thanks to the soon-to-be president, the city was overnight ushered into the limelight.

Three tons of decorations provided a splendid costume for the city that day. The streets were ornamented in red, white and blue decorations with flags plenteously hanging at residences and businesses.

Some 495 deputized patrolmen, recruited from Elizabethton’s citizens, significantly augmented the police department's normal force of five men. Badges were ordered for the “policemen-for-a-day” recruits. Also, a squad of State Troopers as well as local Boy Scouts added their services to the event. After presentation of a huge city key by City Manager, E.R. Lingerfelt, Hoover witnessed an impressive reenactment by the Tennessee National Guard, comprising two batteries of artillery, a machine gun company, aviation corps, light artillery and two companies of infantry. Further, factory whistles within the confines of the city sounded and rock quarries, of which there were many, ignited a barrage of dynamite. While all this was happening, numerous airplanes flew over the battle site dropping a white column of smoke around the pseudo-warriors.

Following a reception for Mrs. Hoover, the Republican nominee rode in a parade headed by more than a hundred pure-blooded Cherokee Indians. This was followed by covered wagons and floats depicting historic epochs in the progress of this section.

A modern Indian camp was erected on the banks of the Doe River, equipped with an Army field kitchen, Army tents, electrically lighted streets and expert chefs ready to provide meals. The facility was large enough to seat 12,000 people, with additional seating in front of the platform and on the slope behind the stand. Two large nearby fields provided overflow space for those unable to find seating.

The speakers' stand, built on the side of Lynn Mountain, one of the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains, was ready for arrival of its welcomed guest. To handle the expected influx of reporters, a vacant building near the platform was equipped with wire facilities and typewriters that also served as a transmitter for radio broadcasts.

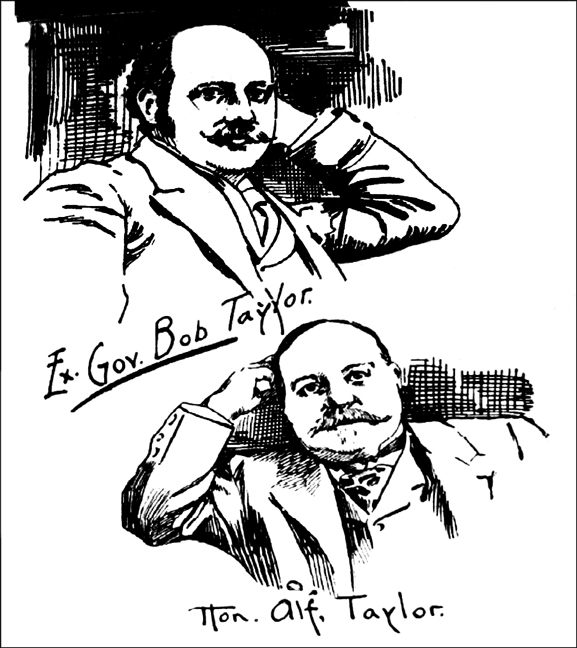

At 3 p.m., 81-year-old famed former Tennessee governor, Alf Taylor, introduced the president, after which Hoover began his 45-minute speech. Subsequently, other features of the day included a football game; the first automobile races ever held in this section, for which a special dirt track had been built; a street dance; and a “Hoover Ball” at the Armory. Hoover's visit to Elizabethton concluded with two final events: a commemoration of the Battle of Kings Mountain and the dedication of the town's second artificial silk (rayon) mill – American Glanzstoff.

After Hoover's exhaustive visit to Elizabethton concluded, his schedule called for a second address at Soldiers’ Home at Johnson City, Tennessee and dinner as the guest of the Chamber of Commerce before beginning the return trip to Washington.

Hoover's key focus on the South paid off; he won 58% of the vote, defeating challenger, Al Smith. However, he would not be so fortunate four years later in a bid to seek reelection due to the Great Depression that would descend upon the country and thwart his chances for a second term.

and Family's Residence in Jonesboro (James H. Quillen VA Medical Center Historical Collection).jpg)

and Family's Residence in Jonesboro (James H. Quillen VA Medical Center Historical Collection).jpg)