Berchie Isenberg Larkins is proud of her legendary grandpa, Jacob Artemas “Artie” Isenberg (1877-1951), one of the last horseback-riding doctors in East Tennessee. She related his story in a recent interview.

The physician and his family lived in Sullivan County near the Washington County line, where Artie provided medical services to the two counties for over 40 years. The equestrian chose horseback as his mode of transportation, preferring it to wheeled vehicles – buggies, wagons and automobiles. He never owned a car.

Artie Isenberg in his younger days

An older Dr. Isenberg riding Old Minnie

The six-foot three-inch medical man maintained between 12 and 15 horses on his farm. He named his first one Thugie after a popular medicine of that day; his last one was called Old Minnie. Isenberg once owned an Appaloosa that would dash off immediately when its rider’s foot was placed in the stirrup, requiring that everything be securely attached to the saddle before mounting. Sometimes Artie and his loyal steed had to navigate creeks, ford rivers and trod deep mud to arrive at his requested destination.

Visits to the sick resulted in stays ranging from a few minutes to several days, depending on the patient’s condition and distance from the doctor’s home. The family would reciprocate by feeding their pipe-smoking special guest hot cooked meals and providing lodging – a cot, couch or chair – near the ailing person. On a few occasions, Dr. Isenberg brought patients home with him so his wife, Lettie, could nurse them back to health while he made other visits.

Mrs. Larkins remembers that her broad-shouldered grandpa usually wore an old gray pin-stripped suit, white dress shirt and worn-out broadband felt hat. Protective clothing included “arctics,” waterproof footwear that fit over regular shoes, and “slickers,” rubberized outer garments used as rainwear. The doctor would occasionally return home so frozen that his wife would meet him at the barn with a teakettle of warm water to thaw his legs and feet and restore feeling to them.

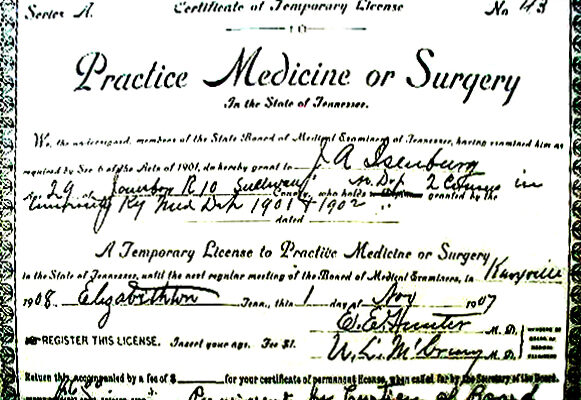

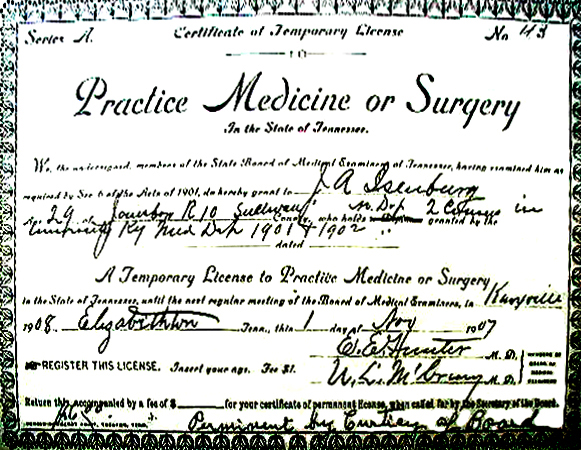

Dr. Isenberg’s formal education began in 1901 when he enrolled at Kentucky University in Louisville. A photo taken in the college’s Anatomy 101 class shows the future physician and several classmates standing behind a cadaver lying on a board supported by two sawhorses. Artie was granted a temporary license to practice medicine or surgery in the State of Tennessee in 1907 from Elizabethton and a permanent one a year later from Knoxville.

The newly authorized practitioner returned to East Tennessee and interned a short time with a Dr. Horne who lived near Colonial Heights. Artie kept a human skeleton in his room until his stepmother abruptly buried it behind their house. She told her stepson the poor soul deserved to be in a grave and not propped up in somebody’s house.

Dr. Isenberg taught classes briefly at Depew’s Chapel near Bay’s Mountain and later at Pactolus School on the Crooked Road. It was at this latter location that Artie met his future wife, Mary Lettie Hunt. The couple soon married and eventually became the parents of two boys and two girls.

Berchie recalled: “My grandpa was hired by the CC&O Railroad to treat worker injuries incurred on the job.” This was short-lived and he soon established his own private practice. Artie’s professional services included being a doctor, dentist and veterinarian. During visits to homes, he often treated their horse, cow, mule or hog. During the flu epidemic of 1919, the doctor spent much of his time traveling from one home to another. He once remarked that he never lost a patient to the outbreak.

Isenberg became known for his accurate diagnostic skills. Although he routinely performed minor surgery, he referred those requiring major operations to one of the closest cities having a hospital – Roanoke, Chattanooga and later Bristol. Berchie recalls when her grandpa would cover a sick person with several blankets, turn the heat up as high as possible and cause him or her to sweat profusely, allowing him to perform a visual perspiration analysis.

Mrs. Larkins further remembers: “A young child had been incorrectly diagnosed with a brain tumor. Grandpa was called in and quickly determined the youngster to be suffering from TB (tuberculosis) of the brain.” Artie loved attending the Appalachian Fair each year in Gray, often providing complimentary doctoral consultations with those with whom he came in contact.

A humorous incident occurred at the home of one of Artie’s female patients. He placed a thermometer in her mouth and waited the traditional three minutesto read it. Afterwards, the woman’s husband asked if he could buy “one of those contraptions.” He explained that this was the first time in all the years they had been married that she had stopped talking for three minutes during non-sleeping hours.

Dr. Isenberg once rode to a residence to assist with the delivery of a baby. After examining the lady, he unexpectedly informed her that she wasn’t pregnant. She disputed his diagnosis, telling him that she been married long enough to have a baby.

Sundays brought an influx of people suffering from dental problems to the doctor’s home. Artie placed two wooden straight chairs back-to-back and asked his patient to straddle one chair and hold on tightly to the back rails. The old-timey doctor then put his knee on the other chair, reached into the person’s mouth with his special forceps and yanked on the bad tooth until it came out. Frequently, the patient was pulled out of the chair, onto the floor and even off of it before the tooth finally released its grip.

Berchie has her grandfather’s priceless collection of books, journals and other artifacts. Unfortunately, the doctor’s medical bag and contents were sold years ago. Isenberg kept meticulous records of his patients’ names, dates of visits and fees charged. There were also several “Memorandum of Births, small booklets detailing the names of the parents and baby. Many entries simply indicated “male” or “female.”

An examination of the collection’s massive data reveals compensation in the form of cash, goods and labor. The books between 1912 and 1918 were especially interesting. Credit was granted for a day’s work at the Isenberg home – working in the garden: $1.00, hauling hay: $1.25, working on the roof: $1.50 and killing hogs: (amount not shown). Another entry reduced a patient’s bill by $5 after Artie was given a pig.

The granddaughter’s collection also contained several personalized prescription pads from Jones-Vance Drug Store (Kertesy Korner) in Johnson City; the Merry Garden, Inc., Broad Street, Kingsport; and the Clinchfield Drug Company, Market and Broad, Kingsport. One receipt on file is a July 11, 1914 order to Masengill Brothers Pharmacy in Bristol for a one-inch spool of “Ad. Plaster” at a cost of $.50 plus $.05 Parcel Post.

About 1951, illness struck the now-aging horseback-riding doctor, greatly restricting his practice. People began picking him up in their automobiles and driving him to a sick person’s home. Artie’s oft-quoted two-step philosophy for his successful medical practice was “making early diagnosis and using the right medication.”

Berchie Larkins concluded the interview by saying that her 74-year-old renowned grandpa “met the Great Physician in December 1951,” concluding a long and impressive medical career.