My recent Dr. Artie Isenberg article prompted Berchie Larkins to provide additional glimpses of her celebrated horseback riding grandfather. The proud granddaughter shared with me a short handwritten treatise authored by Artie on Dec. 12, 1947 titled “Just Another Book – by an Old Horseback Country Doctor – One of the Last of a Vanishing Tribe That Never Can Increase.”

The noted physician related that during the 1890s, aspiring doctors, while still in high school, studied medical books under the direction of their school principals (known as preceptors) before attending medical school: Artie wrote: “Had I known the kind of life these old fellows had to live, I perhaps would not have taken that road in life. I liked to see the sick get well. That was more important than the money I received.”

The curative practitioner fondly recalled his equines: “There were good horses in those days and us old doctors could get them. Our very lives depended on them. If there is a horse heaven, I have some good ones over there – Thugie, Cinco, June and Minnie. They bring back pleasant memories.”

Isenberg remarked on the difficulty of traversing the rough countryside on horseback: “I forded the Holston and Watauga Rivers from Lyns and Cherokee Ford at Kingsport to South Watuaga. There are a few fords between that I never negotiated, but I crossed swollen creeks many times. “I never did swim my horse across. I talked with a man who saw old Dr. Leab swim his horse across the river at Sarah’s Spring. He drowned in the Watauga River.”

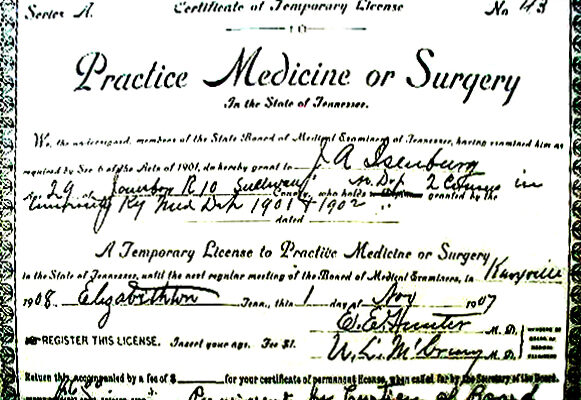

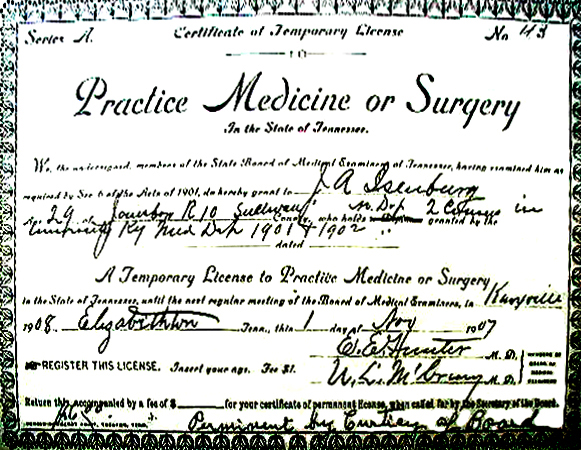

Dr. Isenberg wrote that his profession brought in a modest income. He credited his wife, Lettie, for bringing in about two-thirds of the family earnings, recalling that she once raised turkeys to pay the debt on their five acres of land. My early practice was to cure those whom the other doctors could not or were too careless to cure. I stuck close to my textbooks and made my diagnosis. The diseases we had were typhoid fever, pneumonia, dysentery and diphtheria. They were largely filth bred and filth born. Antitoxins had just come in when I began practice (in 1907). Contaminated water was the rule. Hogs ran loose outside and even slept under schoolhouses and churches. This made the fleas awful.”

Artie remarked that since window screens were unknown to his family then, they had to position a family member by the dinner table to shoo flies while the others ate. “There was not a graded or rocked road in Sullivan or Washington County when I began practice,” wrote Artie. “Good roads make it possible to get sick people to hospitals easier than to get doctors to the sick. I sent many patients to Baltimore to have their appendix taken out. I never did major surgery, but I did know when the surgeon was needed.”

Artie offered some advice for a successful marriage: “My wife and I agreed when we were first married that if one of us got angry, the other was to say nothing. It takes two to make a quarrel. The doctor lamented: “No one ever sang the praises for their old heroes who often left their warm beds to face the cold and went out to save a life as an everyday occurrence.”

Artie concluded by commenting about the changes that occurred in the waning years of his practice: “Horseback doctors were going the way of the dodo bird and passenger pigeon, but we still found some work to do.”