My recent column on the demise of the B-western stars brought immediate responses from Don Dale and Bill Farthing, sharing their memories of the old westerns.

Don Dale sent this note: “Hello Bob, Here I am again responding to one of your columns that rekindled tons of memories. I could go on for a lifetime about the Saturday westerns, particularly at the Tennessee Theatre. When I was a pre-teen, my father and his partner had their accounting office on the second floor, just adjacent to the upstairs balcony.

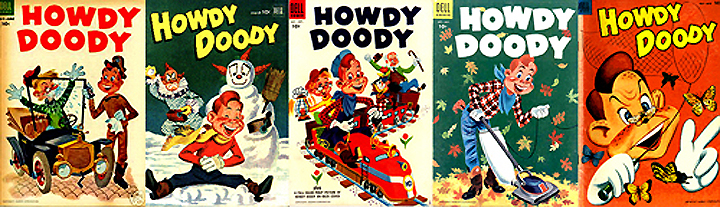

“Almost every Saturday, my brother, Glenn, and I went to the usual double-features and sat in the balcony for free, usually while Dad worked, watching Johnny Mack Brown, Whip Wilson, Lash LaRue, Tim Holt, Hopalong Cassidy movies and on and on. Popcorn was 10 cents. They had an occasional stage show with a cowboy star.

“My most vivid memory is going to see Lash LaRue on stage between a double feature. While Glenn and I were watching the first movie, unbeknown to us, LaRue came through the balcony door behind us and started down the steps where painting equipment was sitting from some touch-up work. He tripped over a ladder and went tumbling down the fortunately carpeted stairs, uttering a few unexpected but expressive remarks as he picked himself up. It was a real eye-opener for us.

“I used to love the cliffhanger serials that accompanied the westerns as well. My all-time favorite was “King of the Rocketmen” — perhaps you remember that one. He wore a silver helmet and turned knobs on the chest of his uniform to soar off — just like Superman. Man, those were the days. As usual, I could go on.”

Bill Farthing offered these words: “I enjoy so much your articles in the Johnson City Press. Today was especially great because I too grew up in the theatre every Saturday watching what I have always viewed as true heroes – the silver screen cowboys.

“My theatre experience was in the Appalachian Theatre in Boone when my brother and I would walk every Saturday and between us pay 34 cents to watch the cowboys, most of the time twice and when there was a double feature we could see both of them twice, forgetting that it was getting very close to supper time.

“I hope I can find a copy of the book you referred to in your article. It is sad that all of the cowboys are gone but one. But in addition to the wonderful memories you brought back to me, add Johnny Mack Brown, Rex Allen and Whip Wilson, along with a whole bevy of horses.

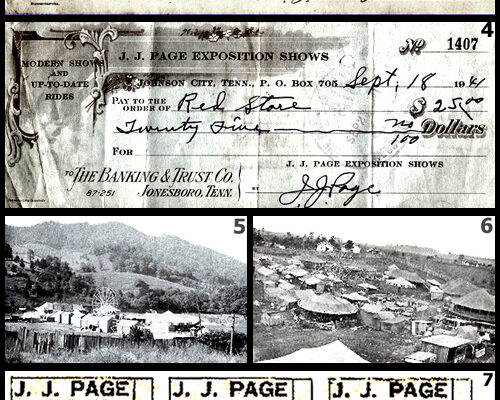

“One of the highlights growing up was to see Hopalong Cassidy in person in Boone. About fifteen years ago while working at Lees-McRae College I traveled with the clogging team and we always joined in the clogging competition at the NC State Fair. One year in a tent right next to the performance tent there was in person Lash LaRue.

“Talk about memories. I have a CD by Rex Allen, Jr. in which Rex Allen, Sr., before his death, did a narration on one of the songs “The Last of the Silver Screen Cowboys.” One line in that narration indicates that the cowboys have died out, but memories don’t die. They certainly haven’t for me and, like you said, all of them had a deep influence on me because right always won. Thank you again for stirring these memories again and I look forward to your next column.”

I received several inquiries as to where Bobby Copeland’s book “B-Western Boot Hill” can be purchased. Most local bookstores could likely order it for you. Also, I found several sources listed on the Internet.