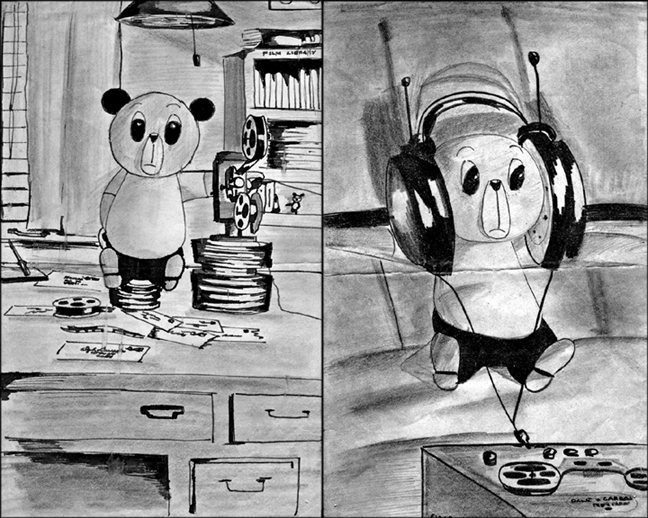

In 1958, the late Dorothy Hamill, Johnson City Press-Chronicle writer, interviewed the executives of Dale and Carroll Productions, a local animated cartoon production enterprise.

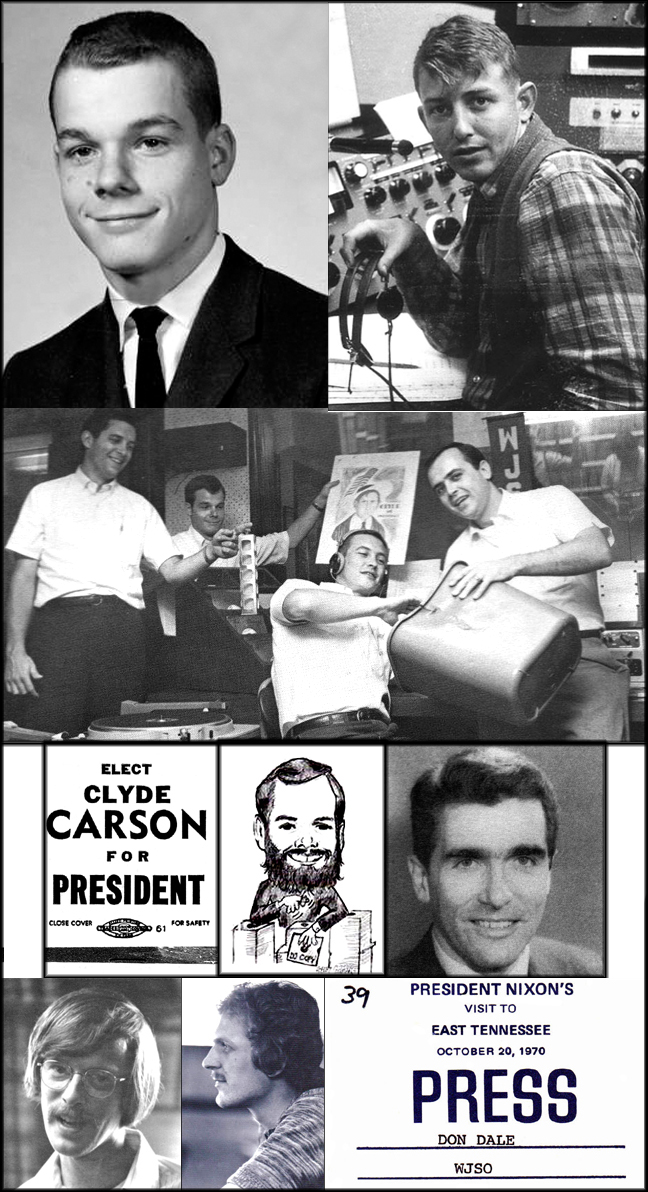

Hamill quizzed Glenn Dale and Larry Carroll (now deceased) about their creation of an adorable little cartoon teddy bear named Henny. Actually, the company’s top brass were enterprising 16-year-old Science Hill High School juniors who possessed an overt desire to produce quality cartoons.

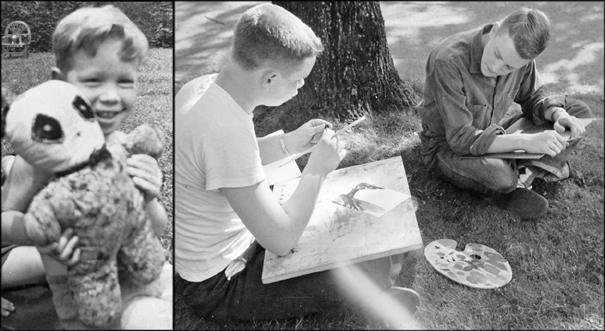

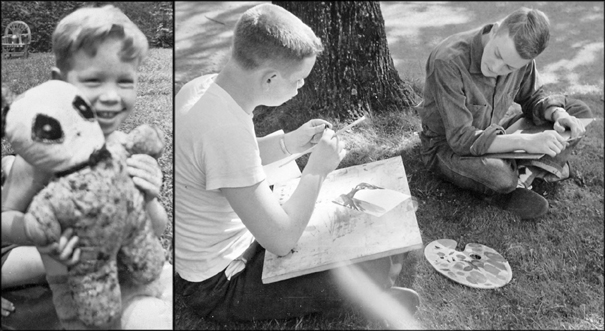

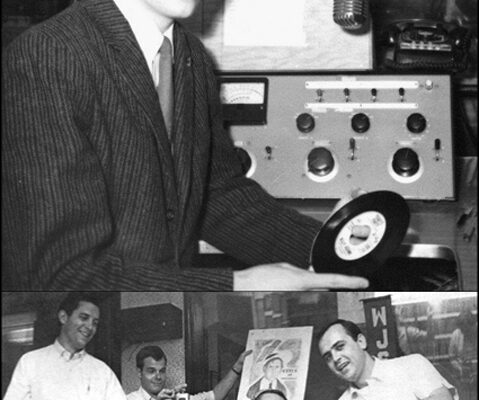

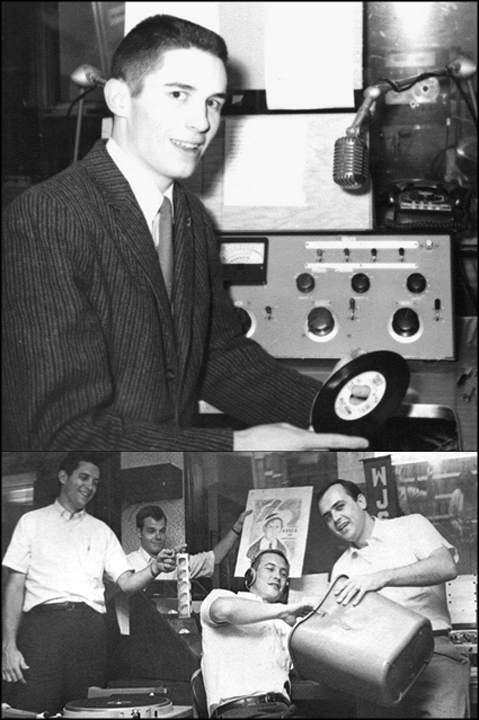

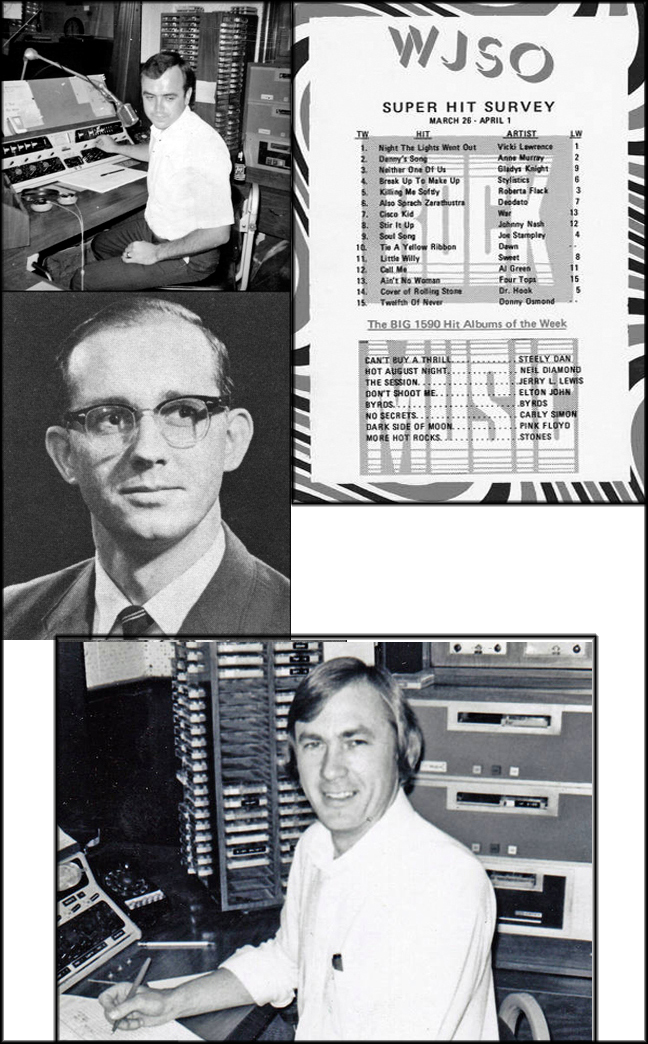

Glen Dale Holds Henny / Glenn and Larry Carroll at Work under a Tree on a Cartoon

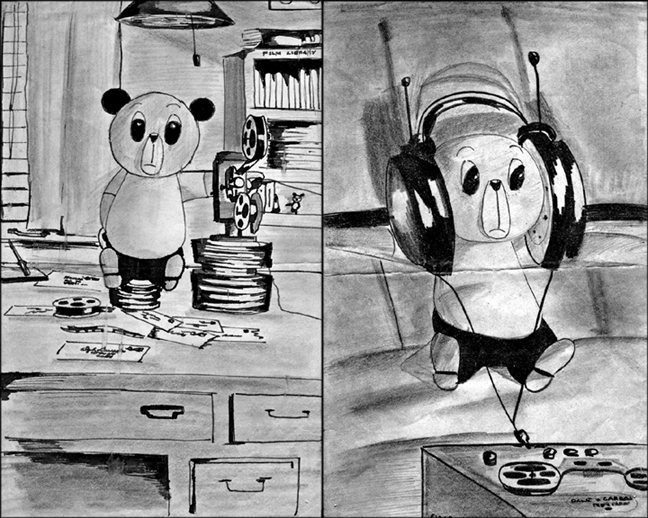

Henny was born in 1956 in a makeshift studio in the Dale home on W. Locust Street. The youngsters fashioned the character from a favorite stuffed animal that belonged to Glenn. The one-room operation was comprised of a couple of adjoining tables, typewriter, cameras, oil and water based paints, record player, reel-to-reel tape recorder, microphone and a storyboard.

Within two years, the indomitable pair generated a sizable quantity of work that included building much of their studio equipment, experimenting with techniques, sketching the hundreds of painstaking drawings necessary for animation and writing story sequences.

Glenn and Larry had known each other since elementary school days. Both were gifted artists and had created some beautiful oil paintings. They attributed their inspiration to pursue the vast technical field of animated film to Walt Disney. Henny became to Dale and Carroll what Mickey Mouse was to Walt Disney. Over time, Henny was almost like a real person to his producers.

The youngsters initially fabricated flipbooks (small volumes containing images on each page that give the illusion of continuous movement when the edges of the pages are quickly flipped). Their journey into film animation received a significant boost when Glenn was given a movie camera for Christmas.

At the time of Hamill’s interview, the young men had five films “in the can” with two more in production. They added a soundtrack for one episode by synchronizing it with the film; they even composed the music score. The youngsters described the tune as being catchy with a fast-beat rhythm. They played their clarinets into the microphone of a tape recorder while Glenn’s younger brother, Don, displayed his talent on piano. They further added sound effects and supplied the all-important voice of Henny.

According to Glenn in 1959: “First, we try to get an idea of the story, making it as original as we possibly can. We feel that originality is very important in movie making. Then we sit around and discuss the story and when we have it in mind, we write down the outline.”

During this process, the talented twosome decided on the characters they would use in the film and the role each would assume. Then they made a series of small sketches that highlighted the main facets of action. The young artists accomplished most of this with pen and ink and, on one occasion, used shoe polish.

A few of the individual pictures were pinned on a beaverboard (light wood-like building material) storyboard (graphic organizer in the form of illustrations or images displayed in sequence for the purpose of pre-visualizing a motion picture, animation, motion graphic or interactive media sequence). With these items visually before them, they began filling in the story line.

Larry further stated: “Every camera angle has to be figured too and then, of course, comes the drawing. For a 7-minute cartoon, over 9,000 separate frames or drawings are needed. If, for instance, Henny throws a ball, a series of sketches had to be made. In each one, the position of the arm was changed ever so slightly.”

Since every sketch had to be filmed individually, the camera was equipped with a device that enabled the boys to film one frame at a time with one of them operating the camera and the other moving the pictures in and out. The initial three cartoons made were referred to as “gags,” which were mainly isolated incidents such as Henny finding a firecracker that explodes.

In one production, “The House that Henny Built,” the little teddy bear decides to build a dwelling in the woods. When he stops to rescue a rabbit being attacked by a fierce bear, the larger animal turns on him causing the forest creatures to come to his aid and even help him build his house. This cartoon was composed of background music, sound effects and spoken lines.

Early in their animation efforts, Glenn and Larry drew in the background, cut it out, superimposed it on the picture, sketched their characters on a sheet of heavy cellophane and placed it on top of the background. That changed when they built a multiplane, a contrivance whereby the camera can be set at the top and take pictures on three different levels, thus giving the illusion of depth.

Dale and Carroll mixed their own paints using mostly watercolor, but used oils for the background. They also constructed sound equipment utilizing a camera tripod for the base, another one on top and a microphone hung on one arm.

In one film, Henny was launched to the moon, but not before his creators extensively researched the subject of outer space to ensure completely scientific accuracy. In the production, they used composer Stravinsky’s music as background and then added tunes of their own composition.

In another cartoon titled “For Sale,” Henny purchases a dog, loses it and then finds it. Once a story was developed, the boys could sketch the action at their individual homes, but during preliminary drafting, it was imperative they work together in the studio.

Glenn recalled when Henny was used in SHHS’s student newspaper, the Hilltop: “The paper used a single cartoon panel that appeared in several editions of the periodical. I guess Henny became a kind of school mascot. Caricatures included Henny in class asleep at his desk behind a textbook, looking at one of the many beautiful young women at SHHS instead of face-forward toward the teacher and standing on the football field with a zero on his ill-fitting jersey. Sometimes, he would appear in large-scale posters in the role of instructor or advertising some school cause or event. It still puzzles me that Henny never graduated from high school.”

One episode featured Henny as a baker who falls asleep and plunges into a batch of fresh dough, requiring him to discard it and start over. Two others involved a character named Bax that was designed by Larry.

The Hamill piece was brought to the attention of a freelance writer in Amarillo, Texas who, using material from the Press-Chronicle and from further interviews, produced an article for national syndication. Shortly, it came to the attention of Disney who then contacted the boys with advice, information and encouragement.

“We later designed effects animation for a student film enterprise in Richmond, Virginia,” said Glenn “that was brought to their attention by the syndicated article. Their last project consisted of three short commercials for a bakery whose motto was ‘baked while you sleep.’”

When Glenn was asked what happened to Henny after 1959, he responded, “Henny is alive and well, although he has been ‘renovated’ more than once and now ‘bears’ little resemblance to the ancient prototype (stuffed animal) on which his film image was based. He has, as far as I know, participated in no film projects since the late 1950s, piqued, perhaps, by the fact that none of his cinematic efforts ever won him an Oscar, not even a nomination.”

Glenn Dale and Larry Carroll expressed a strong desire to enter the animated cartoon field professionally after they finished their education. To that end, they learned all they could about motion picture techniques from printed material and kept abreast of new technology by experimenting with color film, cinemascope and stereophonic sound.

Glenn modestly offered glowing words about the talents of Carroll: “Although we both had artistic talent, Larry was the superior natural draughtsman. He, to the best of my memory, produced most of the cartoon panels for the Hilltop. He consistently produced excellent work animating characters, designing backgrounds and background layouts and in story design. I have no doubt that Larry would have excelled in many aspects of motion picture production and design had he chosen that career.”

_0.jpg)

_0.jpg)