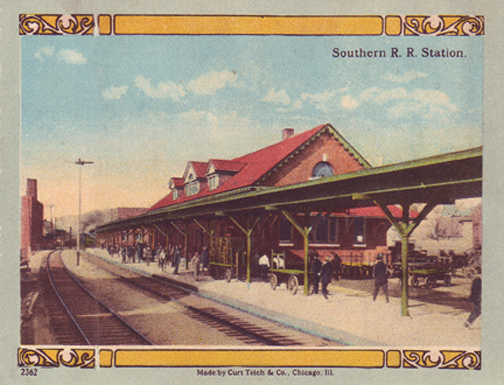

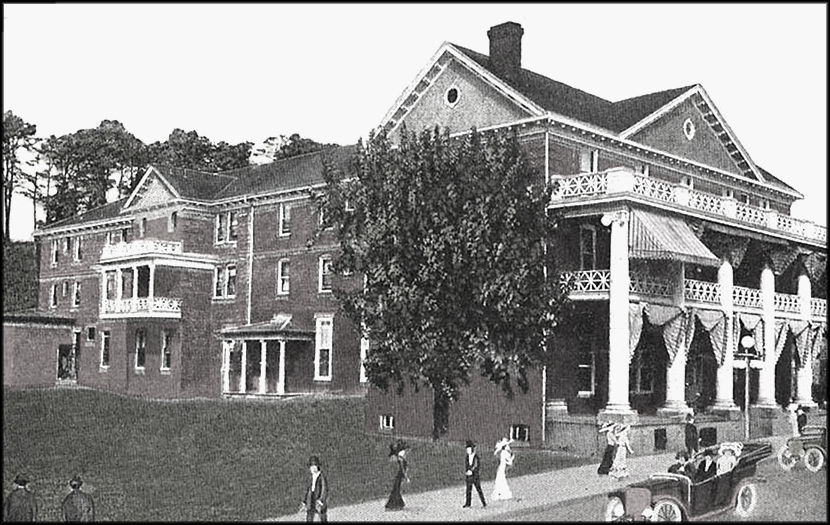

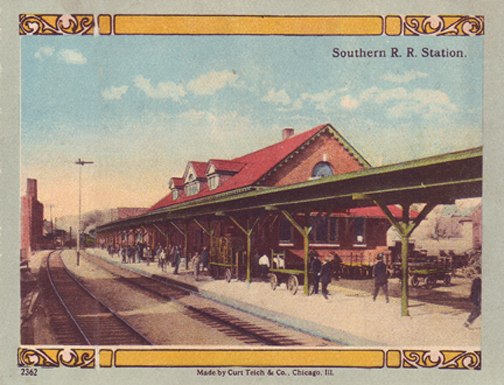

In mid 1973, Dorothy Hamill conducted an interview with Mr. and Mrs. Lloyd Jones to reminisce with them about Mrs. Jones’ 30 years service as ticket agent at the Southern Railway Station, once located between Market and Roan streets.

The city dismantled it in mid 1973 to improve traffic flow in the downtown area. Mrs. Jones said, “It was a gathering place for the town and also for people in the mountains since the railway served a number of North Carolina points. Business people brought lunches and ate in the waiting room. They asked when a train might be coming through and often remarked that the sound of a train was music to their ears.”

Mr. Jones, a clerk of the city’s Clinchfield Railway office and later rate clerk in Erwin, remembered that he met his wife in the Southern station. When the two eventually tied the matrimonial knot, friends amusingly referred to their wedding as the merger of the Southern and Clinchfield.

Mr. Jones remembered that the new station was already built when he came to Johnson City in 1911; he understood that it had been there about a year. The old terminal was operating at the site that became Free Service Tire Company. The new one became a center of attraction.

Mrs. Jones related the words of a soldier from North Carolina who had been in Mexico and was glad to be home: “I wouldn’t take a thousand dollars for the trip, nor give one cent for another.”

During WWII, a Japanese student at Lees-McRae College planned to spend Christmas holidays with her parents in Cairo, Illinois. With a war raging, she needed special permission from the government to make the trip. Hale Williams, special agent, secured authorization and escorted her to her final destination. Mrs. Jones assisted her with hotel accommodations while she was in Johnson City.

Another war trip that was difficult to handle concerned a slight-of-build young woman and six children under five years of age who were traveling to Seattle to join her husband in military service. The depot staff courteously rallied around her and wired the three train stops ahead to give her special attention.

During the war years, about every two weeks there was an embarkation of soldiers on their way to join the armed forces. People were jammed in the waiting room that was permeated with both laughter and weeping. Frequently, a mother or sweetheart fainted.

On June 18, 1932, the railway advertised a special one-day rate of one cent per mile; the usual fare was 3.5 cents a mile. Hundreds of people took advantage of the reduced fee, producing a constant stream of passengers in and out of the depot from 6 a.m. until 11 p.m. After WWII ended, special cars routinely took kindergarten and primary children on their first train ride.

The Tennessean was a popular train that drew a crowd anytime it rolled into town. A baggage and a coach car were appropriately named “Johnson City.”

Several notables stopped off in Johnson City over the years: John J. Pershing, Army general; William Jennings Bryan, attorney in the famous Scopes Trial in 1925; Herbert Hoover, president of the United States; and Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Mr. and Mrs. Jones concluded the interview by lamenting that, although the old train station was sadly going away forever, the memories of it would not die in the hearts of area residents. Thankfully, thirty-six years later, those memories are still very much alive.