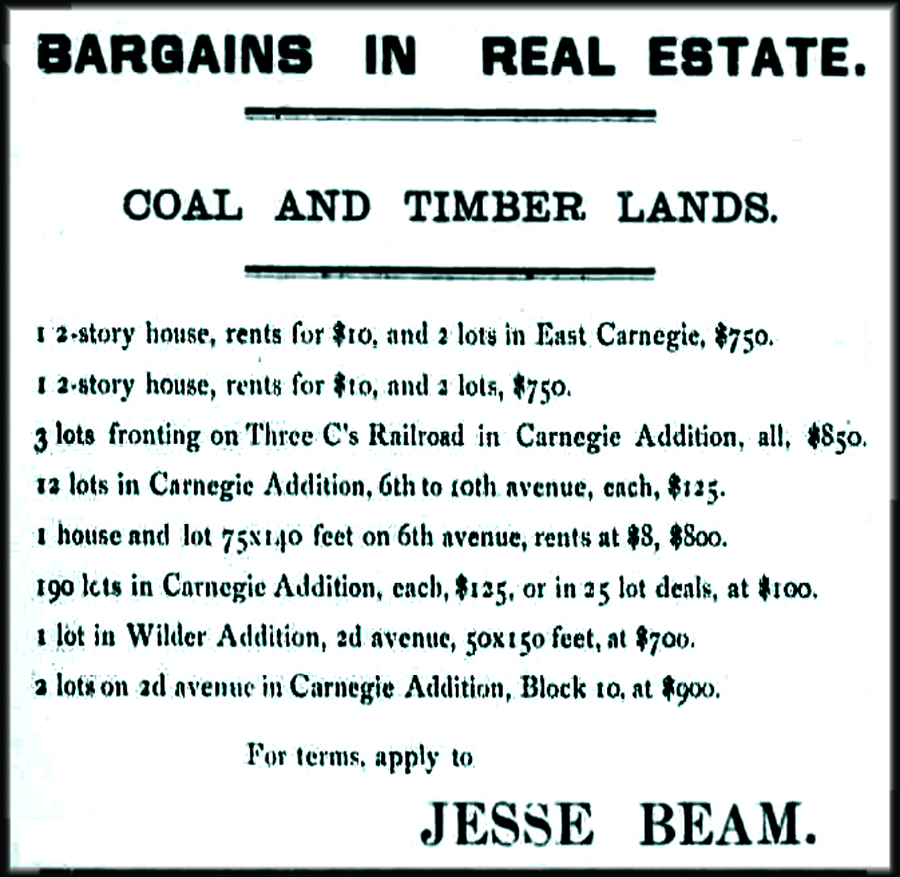

Dr. Ted Thomas, Milligan College Professor of Humanities, History, and German, sent me an interesting clipping from an August 27, 1918 Johnson City Daily Staff that dealt with a visit of four distinguished visitors to the city: Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, Harvey Firestone and John Burroughs.

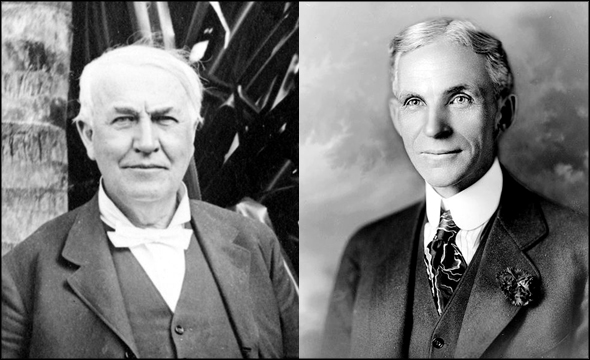

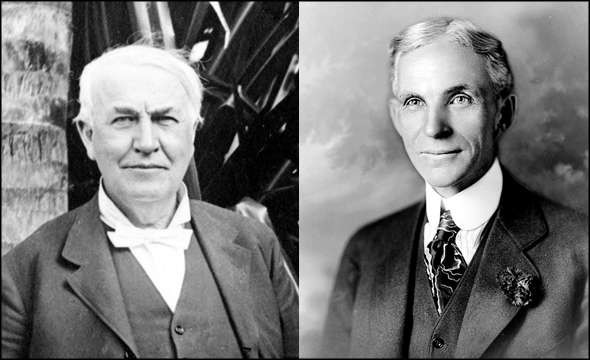

Thomas Edison (L) and Henry Ford

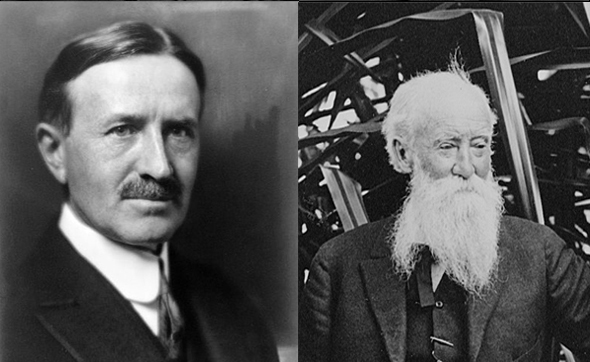

Harvey Firestone (L) and John Burroughs

An unusually brief note in the previous day's newspaper spoke with little fanfare of their arrival. After the newspaper was distributed, the news office was besieged by readers calling to find out where they could get a peek at four of America's most illustrious citizens.

A crowd estimated at 500 to 1000 people turned out that Monday afternoon to greet their guests. The men were en route on their annual vacation trip from New York City by automobile on a mountainous journey that culminated in Ashville, NC.

Thomas Edison was one of the world's greatest inventors, maker of the incandescent light and the sounding machine, which was a cylinder recording device and hundreds of practical electrical devices.

Henry Ford was originator of the automobile that was said to have put the mourners bench out of business and brought more joy and happiness to mankind than any other contrivance.

Harvey Firestone, who specialized in making tires, had business revenue during 1917 amounting to $65 million. He organized the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, a leading firm in the rubber industry.

John Burroughs' notoriety, unlike his companions, was being one of the world's greatest naturalists, authoring hundreds of bird stories, poems and expressions of his love of nature. The curiosity of nearby residents who witnessed the entourage was amply justified.

Accompanying the famous four were H.S. Firestone, Jr., and Russell Cline, the assistant advertising manager of the Firestone Company.

All members of the party arrived in Johnson City by the designated time, with the first to show up being John Burroughs. He captured the public's eye with his Rip Van Winkle appearance, sporting gray whiskers and a linen duster that carried his slightly over 82 years remarkably well.

The bearded outdoorsman alighted from the car in front of the Majestic Theatre and, as he strolled down Main Street, encountered local businessmen Ed Brading and Munsey Slack, who readily recognized him and introduced him to the directors of the Chamber of Commerce.

Ed was president of Cherokee Realty Company, v-president of Brading-Sells Lumber Co. and v-president of Tennessee Trust Company. Munsey was editor of the Johnson City Daily Staff.

Burroughs was astonished that anyone would recognize him and, when he was told there was an article in the local newspaper about his party coming to town, asked for a copy of it, stating that his party was, in fact, interested in the war news. He talked entertainingly of the refreshing trips that the party planned each year.

The men had departed New York a few weeks earlier bound for a trip through the mountains and asked for nothing more than to pitch their tents by the side of a refreshing spring and spend the night resting on mother earth.

The foursome had left Tosca, near Bluefield, West Virginia early the previous Monday morning and camped a few miles from Jonesboro on the Nolichucky River. According to Mr. Burroughs, during that period Mr. Edison actually slept on a hotel bed one night and that was at Connellsville, PA, where they could not find a suitable campsite.

According to the Johnson City Daily Staff: “Two weeks of gypsying through the mountains had been an incalculable benefit to them as was noted by their bronze countenances and clear visions portrayed. All four of them looked revived, well-rested and fully rejuvenated. Burroughs was the most picturesque of the party, being tall and eagle-eyed with keen penetration. One look at his countenance revealed the source of his success.”

Henry Ford, at the solicitation of President Woodrow Wilson about two months prior, had announced his candidacy for United State Senator in Michigan. He made no campaign announcements and refused to spend a cent to secure the favor of either party. The people of Michigan were delighted and told him, “Mr. Ford, you will have little trouble in Michigan in the primary.”

Ford's reply was “I hope so,” which was taken to indicate that he did not care a bawbee (Scottish halfpenny) whether he was nominated or went to build automobiles and submarine chasers at his immense factories in Detroit. Of note, Ford lost the election, but obviously did not mind.

The noted industrialist reverted his energy to war work. Everywhere he had been, the energies of the people, of the United States were bent toward winning the war. He believed that Uncle Sam would sound the gavel at the peace table within a year (as was the case).

Thomas Edison, who was seated with the chauffeur in the car with Mr. Ford and Mr. Firestone, was described as being one of the most modest men who ever visited this section of the country. He was a trifle hard of hearing and when one Johnson Citian went up to him and told him he wanted to shake hands with the greatest man in the world, he blushed and modestly denied the accusation.

Abe Slack, a Staff carrier boy, was fortunate enough to sell Edison a newspaper. The inventor's car had just stopped on Roan Street when Edison waived to him and stopped the car. He gave the youngster a dime and when he reached to get change, Mr. Edison grabbed another paper and passed it back to Ford, telling the boy to keep the change. The youngster was later offered five dollars to sell that dime but refused without hesitation.

The party departed in two large Packard automobiles, with two white trucks carrying their luggage. As expected, no business was conducted during the visit; the fellows were merely enjoying a vacation “far from the madding crowd.” They were communicating with nature, renewing their youth and having their fatigued brains soothed and their nerves healed.

The visitors liked what they saw in and around Johnson City. Mr. Ford and Mr. Firestone especially took a keen interest in everything they observed and were impressed with the number of paved city streets and the city's general air of progressiveness.

Readers might want to further research this subject to learn more about the annual quartet's fresh air excursions. There is a wealth of information available. I wish to thank Ted for sharing this subject with me and my readers.