On June 10, 1984, Mary Alice Basconi, Johnson City Press-Chronicle business writer, composed an article titled, “Circulation Departments Have Their Own 'War Stories.'” It concerned the 50th anniversary of the newspaper, which began publication on June 12, 1934. According to Jesse Curtis, former Press circulation manager, this department of workers produced their own brand of war stories.

The wife of a prominent local citizen called Curtis late one night during a thunderstorm demanding that he deliver her paper. Curtis obliged, honking his horn to alert her as he pulled up in front of her home. This further offended the lady who shouted: “Were you honking at me?”

Another tale occurred in 1943 on the newspaperman's first day on the job. A foot of snow had fallen resulting in three route carriers not showing up. Substitutes were promptly enlisted to deliver papers that day: the circulation manager, Curtis (who was hired then as a mailroom clerk) and publisher Carl Jones.

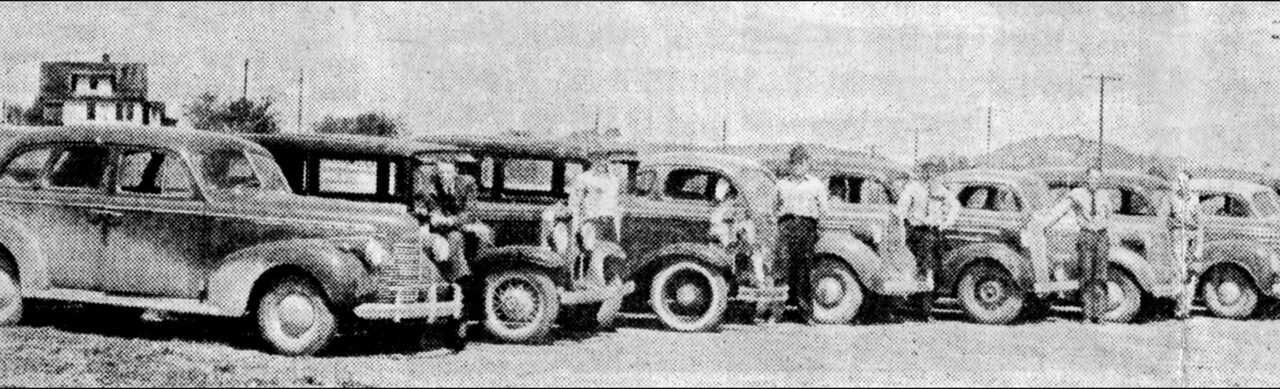

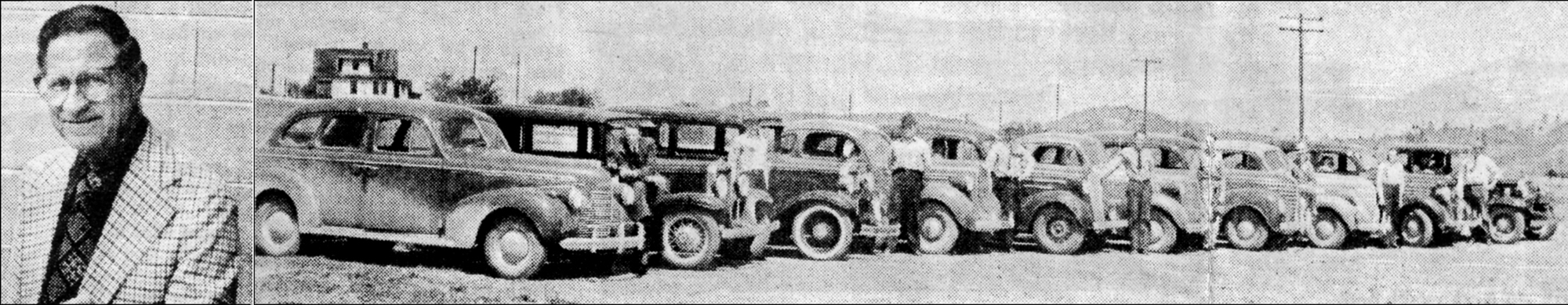

Jesse Curtis. Rural Route Motor Carriers Between E. Main and E. Market Streets in the Mid 1930s

In earlier times, a small newspaper could accommodate customers' late-night requests for papers that didn't arrive that afternoon. Curtis, as manager back then, knew all his carriers' routes. Drivers had to steer their way along mountain roads and foot carriers sometimes had to penetrate wooded areas to make their rounds.

In those days, first-rate carriers were rewarded with a trip on the “Tweetsie” Railroad and a steak dinner. The newspaper was much thinner then with inserts and could easily be folded into a neat square packet and hurled at a customer's porch. The paperboy quickly learned to heave the paper to a precise spot on the porch. That was important to the owner.

Shirley Hayes, who started her 22-year career at the Press-Chronicle in the circulation department, recalled Saturdays as being “money counting days.” Carriers brought in their collections and receipts. “We all had to pitch in and count all those nickels and dimes.” she said.

Curtis remembered when trains had mail cars and papers were distributed by postal service to parts of Western North Carolina. “The paper carrier would get the first papers that came off the press, he said, “and take them to small post offices along his route.” Subscribers would get their paper the same day it was printed, even readers as far away as Chattanooga and as close by as Newland. All of that effort occurred for just 10 subscribers and only one newsstand that sold the Press-Chronicle.

Folks in far-flung communities often asked their carrier to fill a drug prescription in town for them. That luxury evaporated as did same-day home delivery if the patron lived farther than Elk Park, NC.

Curtis blamed television for taking away another bit of newspaper history – the “Extra, Extra” edition hawked on street corners all over the city.

“We used to get these newspapers out,” Curtis said, “when some major event happened, such as President F.D. Roosevelt's passing.” Over time, friendly street-side salesmen were replaced by stoic coin-operated vending racks.

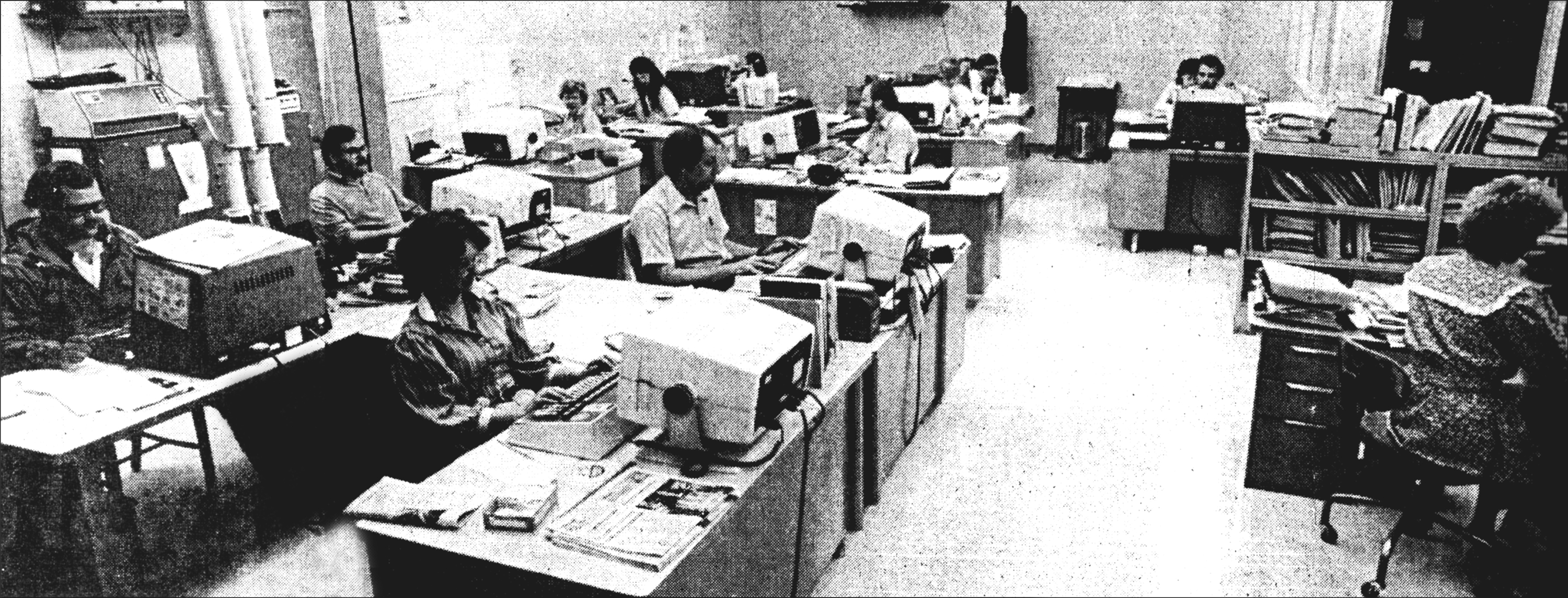

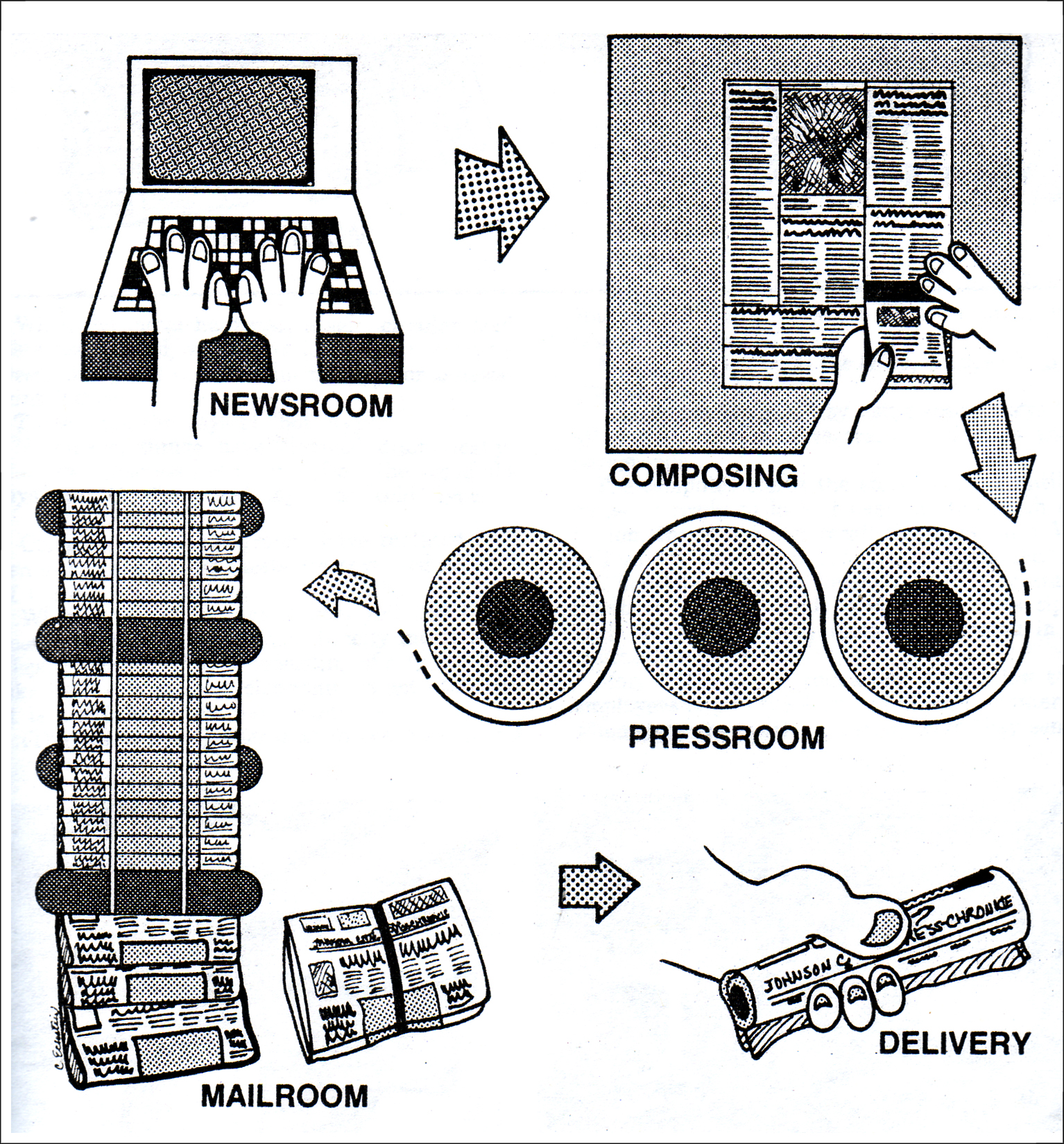

According to C.J. Cody, another circulation manager for the paper in 1984: “Here in the city, we've always had kids making deliveries. Youngsters still make up the bulk of the paper's carriers. Papers were counted in the mailroom, distributed to delivery drivers and taken to drop locations or homes of carriers. The first edition, published at 11:35 a.m., reached carriers by 2 p.m. and customers by 5 p.m. The second edition, published at 2:10 p.m. reached carriers at 4 p.m. and city customers by 5 or 5:30 p.m.”

Cody noted that it was the primary aim of the newspaper to keep pace with the growth of Johnson City and surrounding areas and be positioned to take advantage of what the market was going to do.