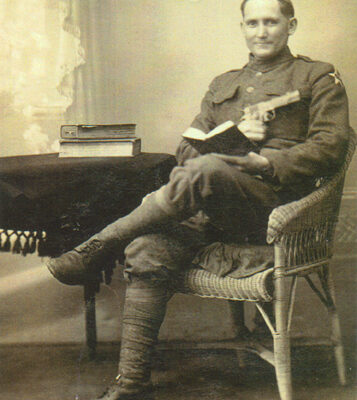

Today’s column is derived from correspondence I received from local residents, Patricia Crowder and Barbara Hobson, daughters of Wm. Roscoe “Ross” Grindstaff who served his country during World War I in France, Germany, Luxemburg and Belgium.

An unidentified soldier from William’s unit penned in beautiful cursive writing a short diary of their division’s travels. When William returned home after the conflict, he placed it in an old trunk in his attic. Years later, Ms. Hobson removed the fragile document, typed it and distributed copies of it to family members. She graciously sent me one. She told me that George Dugger of Elizabethton was in her father’s outfit.

The following are excerpts from the 43 entries written between Oct. 1 and Dec. 18, 1919. The hardships of war are discreetly depicted, along with an occasional pleasurable occurrence such as an observation of the beautiful countryside. Numerous entries relate to heavy fighting, constant fatigue, incessant rain, cold weather and lingering homesickness:

“Our Last Fight. Co. D, 23 Inf., 2ndDiv.”

“Oct. 1 – Found us on the safe side of a big hill in foxholes. Here we had our last warm meal at dusk in the evening for several days to come. At 7:30 marched toward the front line. Reached there and begin digging in on No Man’s Land at eleven (big shell holes).

“Oct. 2 – New men rather excited, the big barrage on at 5:30 sharp. We are at the Dutchman, very few prisoners. The rifles are kept busy at fleeing Boche on open ground, comical sights watching new men shoot, three batteries captured (18 men and 1 sergeant).

“Oct 3 – Full pack made up, ordered back to bed, called out again at nine and moved forward through the Marines. Some excitement here, casualties.

“Oct 4 – Caisson captured and the fun begins, Boshe on all sides and we start cleaning out, 2 batteries, hundred prisoners, several machine guns, heavy artillery play on us all day, several causalities.

“Oct 5 – Under heavy shell fire, some casualties here, we take no prisoners, too much trouble. Marines pass through again, also 2ndand 3rdBattalion.

“Oct 6 – Into No Man’s Land, line broke, lost, line connected again, very tired. I slept from 8 o’clock until daylight the next day.

Nov. 10 – The day was spent mostly playing cards. Their artillery did not get us spotted until the afternoon. We hear all kinds of reports about the Armistice and hope some are at least true.

Nov. 11 – The Armistice signed at 11:00 a.m.

Nov. 16-23 – (Marches to) Stenay, Montmedy, Ethe, Artour Fressen, Saeul, Musch and Heffingen.)

Nov. 24 – Some very nice (inhabitants), some don’t take (to) us very well. Not many Frenchmen here. And our Dutch is very poor. Heavy frosts every night, sleep in barns.

Nov 25 – Blue Monday, rain and sloppy weather, on short rations, two inspections, everything to make life miserable. No idea of moving, getting homesick.

Dec. 8 – Have been traveling down grade all day now going in the Rhine valley, very pretty country, many villages.

Dec. 15 – We followed the river down past an old moss covered castle ages old. Very pretty scenes.

Dec.18 – Drill in the morning. Rainy sloppy night.”

After returning home from the war, William drove an ambulance for Pouder Funeral Home and then a cab for Red J. Taxi Cab Company (located at the current site of the Trailways Bus Station). The family lived on Afton Street near Maple in Johnson City until Mr. Grindstaff went to work for American Bemberg Corporation and moved his family to a residence about a mile down Sinking Creek Road in Johnson City.