In 1909, the year Henry Ford introduced his Model T Ford to the public, there were understandably no automobile dealers or repair shops in Johnson City. Instead, numerous livery stables existed such as Edward S. McClain (W. Market near Boone), Marion McMackin (Locust near Roan) and City Stable (125 W. Market).

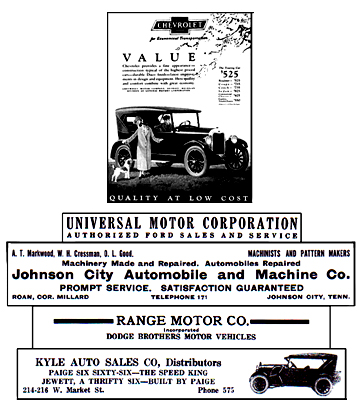

By 1917, the number of car dealerships had grown to three: Burrow Motor Co. (339-41 E. Main), E.D. Hanks Motor Co. (119-21 E. Market) and H.R. Parrott Motor Co. (Ash and Buffalo).

Within eight years, 15 businesses attested to the mounting popularity of the automobile: Auto Renewal Co. (520-22 W. Market), Automobile Electric Co. (138 W. Market), Clark Automobile Co. (808 Buffalo), Glover Motor Co. (235 W. Market), Hensley Repair Shop (102 Montgomery), Herrin-Leach Auto Repairing Co. (244 W. Market), H.L. Hobbs (116-18 Water), Kyle Auto Sales Co. (214-16 W. Market), Muse’s Auto Repair Shop (308 W. Main), Offinger-Sewell Chevrolet Co. (114 Jobe), Range Motor Co. (119-21 E. Market), P.W. Sams (518 W. Market), A.J. Shelton & Co. (339-41 E. Main), Universal Motor Corp. (Boone at King) and Young & Goforth (921 W. Main).

Louis Chevrolet and William Durant founded Chevrolet Motor Car Company in 1911. Six years later, General Motors Company acquired it. According to a 1925 newspaper, Chevrolet engaged in an unrelenting quest to add superior value to its vehicles and compete with Ford’s Model T. To accomplish this, Chevrolet chose a few automobiles for “Speed Loop” tests and selected trucks to “Bump Boulevard” evaluations.

Chevy’s “Speed Loop” was located near Milford, Michigan, where cars were driven around it repetitively. The grueling driving assessment was maintained around the clock throughout the year without regard to weather conditions. In the course of a month, seven Chevrolet cars were subjected to the loop for a combined total of 75,000 miles, providing both routine and abnormal driving conditions that cars would not be subjected to by the typical owner. All models were included in the test group.

Two shifts of drivers maintained a pace of between 35 and 40 miles per hour (a high speed then), stopping only for gas, oil and inspection. The dayshift drove from 7:30 a.m. until 5:30 p.m. with a half-hour off for lunch; the night group worked from 7 p.m. until 6:30 a.m. with a 30-minute midnight snack.

The “Loop,” which had no speed restrictions, included three miles of gravel track banked high at the turns and one mile of level concrete straightaway. The section of road leading from the “Speed Loop” to the inspection shop had a 11.6% grade. When each car traveled 1000 miles, it was taken into the shop where it incurred a thorough washing followed by a meticulous examination. This was the only time the vehicles were under cover. An assessment report was then issued to management.

After a vehicle reached 40,000 miles on its odometer, it was taken into the shop and torn down for additional precision analysis. Often, the inspectors found opportunities for major and minor refinements. No detail was considered too insignificant for consideration of design changes in future models.

Chevrolet trucks were also under continuous testing along “Bump Boulevard.” This consisted of an old unpaved farm road, much like those in rural areas that crossed the 1,146-acre proving ground. The defects and irregularities of this road were purposely left intact to challenge the trucks.

The two testing programs were not without a price. The company used about 4,500 gallons of gasoline monthly, but considered the effort well worth the price.