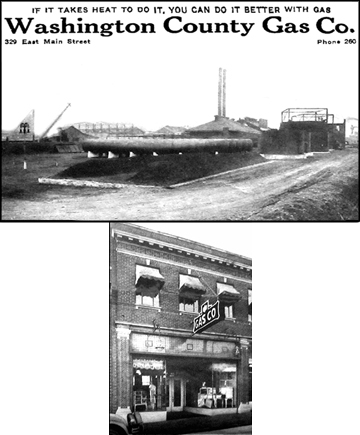

An advertisement from a 1930 Johnson City Chronicle and Staff News stated, “If it takes heat to do it, you can always do it cheaper with gas.”

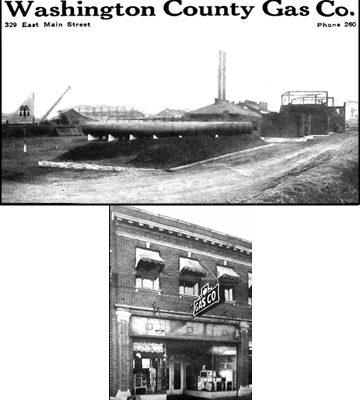

The business paying for that ad was the Washington County Gas Company, which began operation in 1914 in Johnson City. It ushered in the first gas to the city, which then was manufactured from coal. The firm constructed a coal-gas manufacturing plant along the south end of Tennessee Street near Walnut adjacent to the Southern Railway tracks.

A 1917 Johnson City directory shows the business office located at 240 E. Main (future site of the Nettie Lee Ladies Shop). Initially, service was available only to Johnson City residents, but a growing demand for gas prompted management to enlarge the plant in 1922, doubling capacity and allowing gas lines to be extended to serve nearby Elizabethton. The growth of the company resulted in the company changing its name to Watauga Valley Gas Company.

By 1923, the office was relocated just up the street to 329 E. Main where it shared the location with the National Life and Accident Insurance Co., Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. and National Mortgage Co. It was sandwiched between the Wofford Building on the west and the businesses of Security Investment Co. and G.W. Toncray and R.P. Eaton (notary publics) on the east. The location would later become the site of the Home Federal Savings and Loan Association. In 1928, the general manager of the operation was E.J. Wagner.

During 1946, there was a shift in technology. The manufacture of gas from coal was discontinued and replaced with gas made from liquefied petroleum (propane). The company’s new facility had an output of one million cubic feet a day, which more than doubled the capacity of the discontinued coal-gas facility.

One year later, the business was sporting a new name – the Watauga Valley Gas Co. located at 331 E. Main. Three years later, the address was shown to be at 334 E. Main. The officers were H.W. Gee, president; T.F. Dooley, secretary/treasurer; and L.L. “Skinny” Hyder, salesman. The new business logo was “Gas Has Got It.”

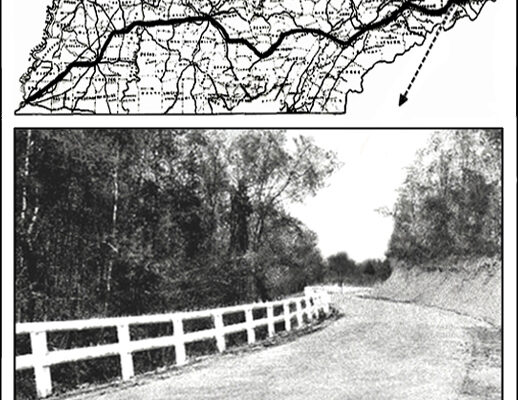

Beginning in the 1940s and continuing into the early 1959s, officials of the local gas company and another firm, the East Tennessee Natural Gas Company (ETNGC), worked diligently with the Federal Power Commission to bring natural gas into East Tennessee. After several long frustrating delays, the FPC granted a certificate in November 1952 to ETNGC for construction of a 100-mile pipeline from Knoxville to Bristol.

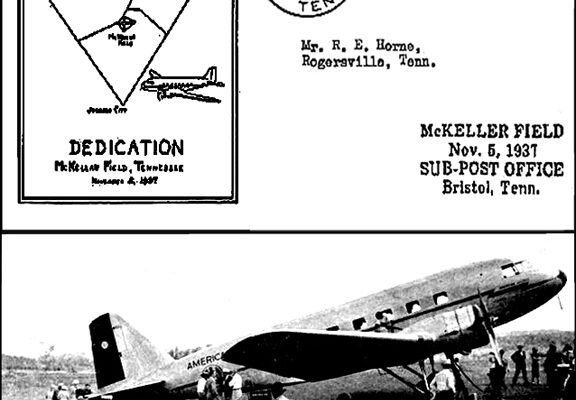

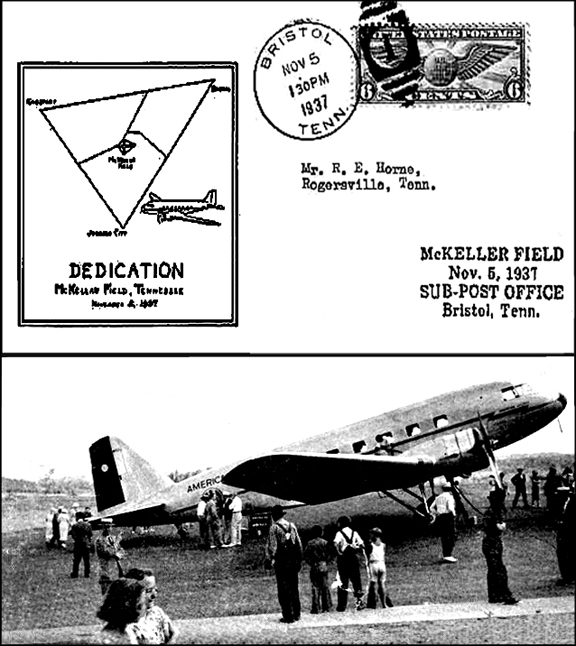

Work began on the project in August 1953, the same month the board of directors of the gas company adopted a new name, the Volunteer National Gas Company, which was indicative of the expanded territory to which service was to be rendered. The arrival of natural gas into the Tri-Cities area was a welcomed and significant event. A ceremony was held on January 16, 1954 at Tri-Cities Airport with Senator Albert Gore, Sr. lighting the long-awaited flame. In attendance were more than 200 area leaders.

With the availability of natural gas in the surrounding area, the company increased sales by more than 300% and added 500 additional customers during 1954. By 1976, the company had 8,000 customers in Johnson City, Elizabethton, Kingsport and Greeneville.

From its humble beginnings in 1914, gas became a true success story.