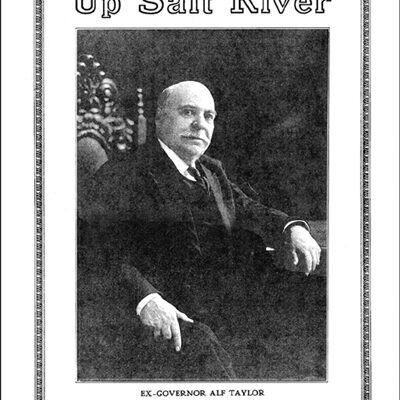

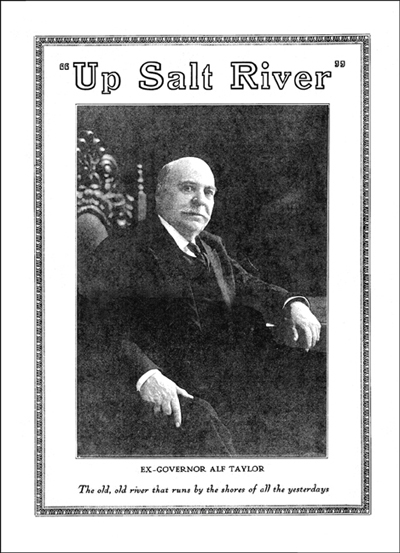

Johnny and Patsy Starnes own an attention-grabbing brochure titled “Up Salt Creek.” The four pages deal with a prominent lecture that was frequently delivered by then Ex-Governor Alf Taylor at various locations throughout the state of Tennessee. The date is not specified but is known to have occurred between the time he left office in 1923 and his death in 1931.

The cover contains a large photo of Alf Taylor and a caption underneath that reads, ‘The old, old river that runs by the shores of all the yesterdays.’

According to Patsy, “Johnny received the pamphlet from the effects of his great grandfather, John Bunyan Wolfe, who built a furniture factory in Piney Flats around 1888 and was responsible for early electricity and telephones in the area.”

The expression, “Up Salt River,” is believed to have originated in Pike County, Missouri near the mouth of the Salt River in the early 1840s. A political aspirant suffered defeat in an election for a state office. Undaunted, he relocated further up the river, ran for office again and lost the election once more. Later, when people inquired about the persistent candidate, they were told, “he is still moving up Salt River and running for political office.” That was the gist and jest of Alf’s application of the phrasing.

The brochure is a review of Alf’s lecture by eight critics. An excerpt of each is listed below.

DeLong Rice, author of the book, “Old Limber or The Tale of The Taylors,” offered the most eloquent expose: “’Up Salt River’ is the title of the half-humorous, half-serious, all-beautiful discourse of the popular ex-governor who, but a little while ago, caught the attention of the whole country by setting a serious and able campaign speech to the music of running hounds.

“In the political campaign of 1920, when the suffering suffragists of Tennessee were listlessly bracing themselves for the biennial grist of aged platitudes and statistical ‘punk,’ Alf Taylor, keen reader of the minds of men, suddenly rolled his party platform, with Code and Constitution, into a master musician’s baton. And out of the shadows of the Appalachian peaks, came the wraith of ‘Old Limber’ and his flying chorus of Walker dogs and they holed the Tariff and treed the League of Nations as the melody of the chase was written on immortal bars in the forensic history of Tennessee.

The Johnson City Chronicle offered its assessment of the talk: “Folks in this section are glad, though not in the least surprised, that the lecture is being received with such enthusiasm everywhere it is heard. Uncle Alf, as he was popularly known thru the years of his political activity, is always a speaker worth listening to. Blessed with a platform presence which is not the heritage of many men, with perfect command of English, with the power to sway his audience at will through the gamut of emotions from hilarity to tears and, most important of all, with a never-failing basis of sound thought underlying his words, he never fails to captivate his audience and, in doing so, to give it something worth-while to think about.”

The Erwin Weekly Magnet sensed that the Governor shone forth in all of his old-time oratorical splendor: “Reciting much of the early history of Tennessee, ‘Mother of States,’ he told how nearly all of its distinguished men at this time or another had taken the trip ‘Up Salt River.’ He called attention to the fact that Gen. Sam Houston, first president of Texas and later its governor was a native Tennessean, as was David Crockett, hero of the Alamo. He mentioned 50 celebrated names of Tennessee men who became leaders in national affairs.”

The Knoxville Sentinel noted that Alf’s speech sparkled with wit and wisdom, delivered in the inimitable Taylor style: “He appealed to his audience’s sense of humor but sent his hearers away thoughtful. Gov. Taylor is one of the few remaining orators of the old school. For eloquence, diction and word artistry, he has no superior and a few equals. For almost an hour and a half, he held his audience as if in the hollow of his hand. As a prelude to the lecture and as a compliment to a distinguished visitor, the Lafollette Concert Band rendered a musical program of about 30 minutes.”

The Fayetteville Observer commented that Gov. Taylor had the vim and vigor of a 25-year-old man and was a speaker well worth listening to: “The lecture abounded in quips of fun which kept the crowd in a good humor, but underneath it lay of foundation of sound thought; he wore his way through the various stages of success, misfortune and hope and closed with a magnificent tribute to the Christian religion.”

The Nashville Banner said the people of the capital city had the pleasure of hearing Ex-Governor Taylor deliver his new lecture: “It proved to be an excellent one and included a beautiful sermon and magnificent oration pronounced by many to be the best ever heard here.”

The Memphis Commercial Appeal called Uncle Alf “an optimist, whose philosophy is filled with spirit of human kindness: “Governor Taylor is giving a message to the world, which reflects the mellowness of a man who has smiled at adversity. In his jaunt, he gives a review and reminiscences from the mind and heart of a man who was not embittered by political defeat. ‘What I don’t know about Salt River isn’t worth knowing,’ said Uncle Alf. ‘Life is not a dream of ease. There is generally a horrid nightmare with every dream. There are ups and downs. One always finds plenty of company ‘up salt creek.’”

And finally … The Memphis News Scimitar indicated that Uncle Alf Taylor spread a lot of joy, mirth and good feelings wherever he traveled: “He is about the most delightful personage in the state and one of the most beloved. He is young in mind and imagination, buoyant, optimistic and cheerful. The only effect that the years have had on him is to give him wisdom. His faculties are undimmed and he stands a monument to perpetual youth.”