Ms. Louise Bond Alley has a remarkable Civil War story relayed to her by her mother, Edith (Mrs. John) Bond that was passed down from Edith’s mother, Rebecca (Mrs. James) Clark and grandmother, Magdalena (Mrs. Abram) Sherfey.

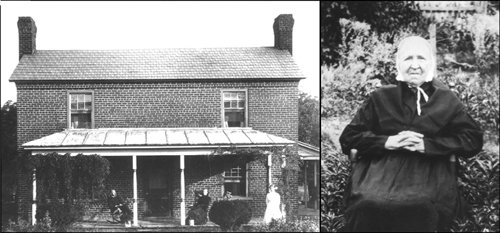

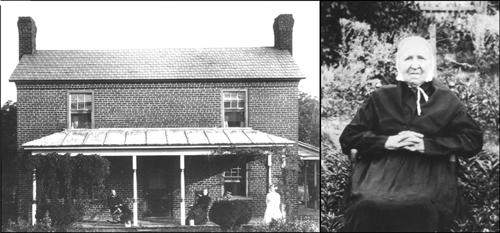

In the mid 1800s, the Abram Sherfey family owned 300 acres of land along what is today identified as 282 Woodlyn Road in the east section of town. Railroad tracks bordered it on the front and Brush Creek at the back. Abram, a German immigrant, built a two-story house using hand-made brick after initially living on the property in a “soddy” (grass and dirt) house and log cabin. Magdalena rode the horse that tramped the brick before it was cut.

Between 1862 and 1865, the couple altruistically turned their home into a makeshift Civil War hospital that served soldiers on both sides of the war. Louise attributed this bold move to her family’s anti-slavery belief and deep-rooted Church of the Brethren faith. The East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad played a significant role in the viability of a hospital in that locality. Before the war, it regularly stopped at the Sherfey farm for gratis wood and water.

During the war, train personnel dropped off critically wounded and sick soldiers and picked up recovered ones. Because the conflict, the train might roll by anytime during the day or night, daily or weekly. Keeping track repaired was an ongoing concern. The train’s mournful steam whistle wailing in the distance signaled the approach of the massive locomotive. If a recovered soldier was ready to board, a family member rushed him to the tracks and flagged down the train.

The two-story house had four 18×18 feet rooms, two upstairs and two downstairs. Up to ten soldiers slept in each room on pallets on the floor. The downstairs had a kitchen and dining room where family members resided. A fireplace was along the back wall. Three porches, one on the front and one on the ends of the kitchen and dining rooms, were used to store and prepare food when the house became unduly crowded with soldiers.

A trapdoor in the kitchen floor near the fireplace was the only access to the dirt cellar. It was covered with a rug when not in use. Hams, bacon, dairy products and other items were stored there. Meat was first cured in the smokehouse and moved to the cellar. The family raised such provisions as garden vegetables and livestock and hunted wild game, obtaining additional supplies wherever it could be found. Grain was ground at local mills, such as nearby St. John’s Milling Co.

One constant threat was roving renegades from both sides of the war stealing whatever supplies they could confiscate. When the peril became known, family members turned livestock loose and chased them into the woods for their protection. Water was arduously carried to the house from a nearby spring; large rain barrels accumulated runoff for washing purposes. Water was recurrently boiled in the fireplace to treat soldiers’ wounds and to wash and reuse soiled dressings.

When possible, Magdalena sent a letter to the family of each new arrival informing them of their loved one’s location and medical situation. Rebecca, about 9 or 10 at the time, penned letters for her mother utilizing her beautiful handwriting. Sometimes a note prompted a response from a family; often, it did not. Magdalena made use of an 1860 medicine book that is still in the family to prepare remedies for the soldiers. She made poultices, salves and syrups and grew her own herbs.

The family fed and cared for their welcomed guests’ medical needs, bathed them and washed their clothes. Children and adults from nearby farms and soldiers, who were well enough to assist, helped with the chores. Since death was an ever-present unwanted caller, Abram made and kept a supply of handmade pine or poplar coffins ready and buried the deceased in the orchard on the west side of the house, carefully identifying each grave. At war’s end, the government transported the remains to the states where the soldier had resided.

There was rarely any friction at the hospital even with soldiers from both sides of the conflict present. The men wanted to get well enough to return to their homes; for many, the war was over. The Sherfeys received no financial reimbursement from the Union or the Confederacy. The lone exception was an occasional supply of food sent to them from the government by train.

When the hostilities ended in 1865, food supplies had become even scarcer, especially salt and sugar. Salt cost $100 for a 50-lb. barrel and sugar was even more expensive. Payment for goods had to be made in gold coins because merchants would not accept anything else, especially confederate money. Magdalena left behind an old and fragile diary, held together by strings that recorded her 225 midwifery efforts between 1866 and 1873. Louise regularly made notes from stories her mother told her.

In the 1970s, a family from Indiana located Louise and presented her with one of Magdalena Sherfey’s Civil War letters that had been sent to a soldier in their family. Unfortunately, the young man did not make it home alive. Moved by their gracious gesture, Ms. Alley insisted that the family keep it.

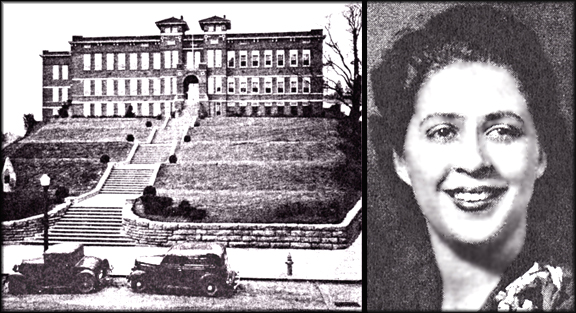

Edith Bond lived in the old historic house until she married in 1920. According to Louise: “She walked the railroad tracks from her home to the streetcar stop at Fairview and Broadway in Carnegie, a distance of three miles. She then hopped on a streetcar and rode to Science Hill High School downtown.

“Mother died in 1978, she said. “That old house played a long and pivotal role in our family’s history. Hopefully, a state historical marker will one day be placed at the site.”