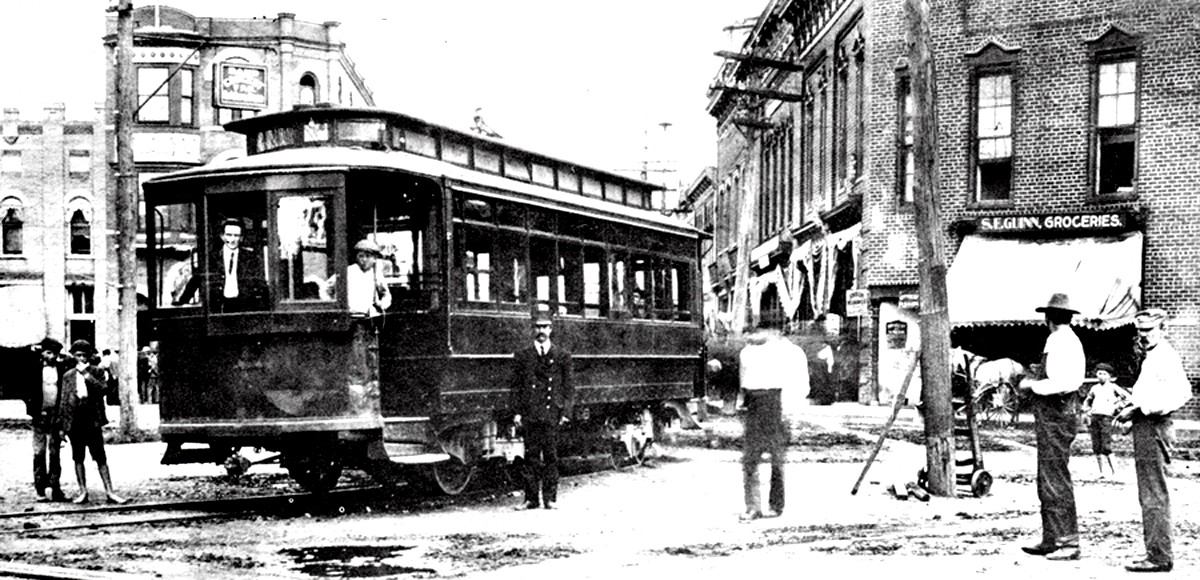

Local history can sometimes be found in unlikely places, such as a May 1931 Electric Traction magazine article that provided surprising particulars about the city’s switchover from streetcars to buses. Also included were two photos showing the interior and exterior of the new mass transit vehicles.

It was estimated that between 1892 and 1921, over a million passengers rode the city trolley along nearly a quarter of a million miles of parallel track. However, the next 11 years signaled a significant decline in streetcar usage, caused by a steady increase in the number of private automobiles on the road.

The town was facing a dilemma in 1931: either buy several new pricey streetcars for replacement of older cars and expansion of new routes or switch to buses. Additional trolley lines meant extra track and overhead power cables. While trolley routes were pretty much fixed, bus routes offered flexible itineraries.

That year, Johnson City Traction Company management proposed to city officials that streetcars be replaced with buses. The city agreed and acquired five new Mack Model BG 21-passenger vehicles. Mr. D.R. Shearer became direct supervisor over the bus system and T.C. Land served as superintendent of operations.

The city immediately began planning numerous routes and experimented with trial runs so as to offer transport service to as many residents as possible. Fortunately for streetcar motormen, most were redeployed as bus drivers.

Pomp and ceremony heralded the inauguration of bus service for the city’s 25,000 residents. City officials and civic leaders assembled at the John Sevier Market Street bus terminal where the National Soldiers Home band orchestrated a 15-minute band concert.

Charles E. Ide, vice pres. of the East Tennessee Light and Power Co., presented the key of the first official bus to Mayor W. B. Ellison. After the ceremony, the mayor, accompanied by several city officials and executives of the company, boarded the bus.

Ellison placed the key in the ignition, turned it and started the vehicle, thus launching Johnson City’s first bus service. Civic leaders, visitors and educators were then invited to take short trips around town to fully demonstrate the benefits of the new impressive medium.

The Mack buses were well lighted and had seats upholstered in genuine grade leather. Heating was provided by a hot water system and ventilation came from four waterproof ejector-type ventilators in the roof.

Reduced vibration was realized by employing rubber extensively throughout the chassis and installing rubber shock insulators at all points of spring suspension. Gear operation consisted of first, second, third, fourth, direct and reverse.

The new buses contained Ohmer fare registers that, on demand, calculated and printed out a summary strip of paper showing the number of cash fares, tokens, school fares and transfers received.

Riders were charged 10 cents cash or a token per ride. Four tokens could be purchased for 30 cents; additional ones beyond four were sold in multiples of two at 7.5 cents each. Youngsters under 16 years of age rode for a nickel.

Customers were treated to services they had not experienced before. With each passing day, the public observed more buses on the streets and fewer trolleys. The endearing little nostalgic streetcar with its ever-familiar “clang, clang, clang” soon rolled off into yesteryear bringing about the end of a colorful era of history.