Kate Watson and Mack Houston have warm feelings for Cave Springs School that stood near Milligan College between 1909 and 1955. During the 1930s, both individuals attended this eight grade two-story wooden institute alongside Buffalo Creek, east of a bridge on State Route 359 (Okolona Road).

Mrs. Watson’s father, Samuel S. Cole, a renowned educator for 45 years in the Carter County school system, was principal at the grammar school for 17 years. “I started school at age four,” said Kate, “because of my fondness for Mary Buck, the first grade teacher. I graduated from Happy Valley High School at age 16.”

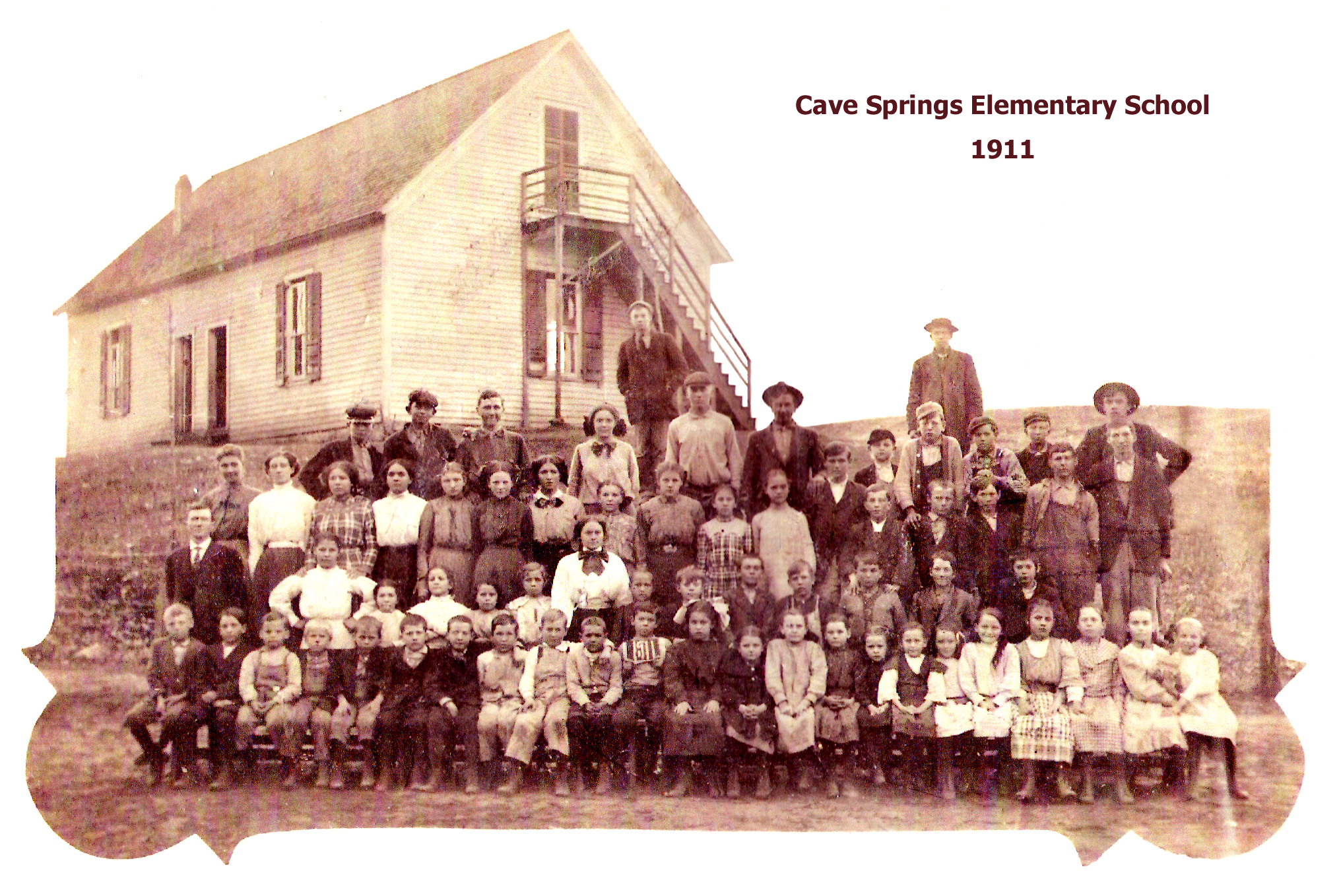

The principal’s daughter supplied several old documents and photos. Property for the new school was purchased in Nov. 1906; classes commenced with the 1909 school year. Cave Springs School served Okolona youngsters, while nearby Silver Lake School was for Milligan youth.

According to Mack: “The schoolhouse had four classrooms, with two grades sharing each one. Each room held between 30 and 40 students. All classes were downstairs; the upstairs was used for storage. The school had three principals over the years – Mr. Cole, Wayne Gourley and C.C. Price. Mary Buck taught grades 1-2; Blanche Gourley, 3-4; Francis Anderson, 5-6; and Samuel Cole, 7-8. Courses included Penmanship, Arithmetic, English, Geography, Reading, Health, American History and Tennessee History. The school provided textbooks for students. Each room had a pot-bellied stove either in the front or center of the room. One student chore was to go outside each morning and carry wood into the classroom.

“Classes were from 8:00 am until 3:30 pm, with a 30-minute lunch break and two 15-minute recess periods. Our only time off was one or two weeks at Christmas. Students brought a lunch box or brown paper bag that often contained jelly biscuits to class each morning. There were no school buses. Most of us walked 2-3 miles each way, some coming from as far away as five miles. That was pretty rough in cold weather. School officials tried to locate a school every three to four miles so kids did not have so far to travel. In the fall, we had apple trees along the way that allowed us to stop for a treat. We crossed creeks, sometimes using sticks to vault across streams. These were fun times.”

Mack commented on the school’s crude bathroom facilities: “Two heavy rough-hewn oak board “four-seater” outhouses stood near the school, one for boys and another for girls. He related a daily ritual at the school: Mr. Cole started school each morning by opening a partition between his office and an adjoining classroom. This provided a small auditorium for the whole school to convene. Teachers stood along the back while students sat on the floor down front.

“Mr. Cole read the Bible, led in the Pledge of Allegiance and had prayer. Students then went to their individual classrooms for Bible verse memorization. We each recited one verse every morning. There were strict rules for conduct while at school; cursing, bullying and fighting were strictly forbidden. Students responded to their elders with ‘yes madam,’ ‘no madam,’ ‘yes sir’ and ‘no sir.’ Minor infractions meant staying in from recess and writing repetitive sentences on the blackboard; major ones resulted in a trip to the principal’s office for a paddling.”

Mrs. Watson said the school had a code of discipline with the number of licks corresponding to the severity of the infraction. Boys were paddled on their behinds. The Elizabethton Health Department sent a nurse to school once a year to administer shots to all the kids. She always wore a white uniform, typical of that era.

“The area contained numerous itinerate families working on local farms,” said Mack, “They earned wages of 10 cents an hour. Most were large families and left a big void when they moved on to other work.”

Kate said times were so tough that students occasionally missed classes in order to provide assistance on the family farm. Most of the students were poor. Teachers brought extra food, clothing and personal hygiene items each day for those who were disadvantaged. Students wore patched hand-me-down clothes. Girls wore dresses, usually fabricated by their mother from cow food bags and referred to as “chop” bags.

Mack remembered Mr. Cole dismissing school when snowstorms hit the area. Parents came to school with heavy clothing and escorted their youngsters home. Houston commented about recess activities: “Boys and girls played together. We had dodge ball and baseball using sponge rubber balls. My favorite sport was hitting a small ball with flat boards or bats.”

Kate said she often stood on a hill near the school and watched cars go down the Erwin Highway: “Barely 3-4 cars passed in an hour. It was exciting to see the big Greyhound Bus whiz by on its way to Asheville.”

Mack commented about beautiful Buffalo Creek that ran within 150 yards along the school’s east and north sides. The boys fished for suckers and then dammed the creek to form a swimming hole. The former student added: “We drank water that was cold and delicious from an old spring below the school that came out from under a rock near Buffalo Creek.”

Cave Springs School remained in operation until a devastating fire destroyed it in the early 1940s. It was summarily rebuilt, but later burned a second time. Overheated stove flues were a frequent source of fires.

Cave Springs School closed its textbooks forever in 1955. After sitting idle for seven years, it was razed in 1962 and the property sold at auction. A brick house now stands at the site as a memorial. On April 8, 1997, the Tennessee General Assembly enacted Senate Bill No. 1128 designating the bridge near where the old school stood as the “Samuel S. Cole Memorial Bridge.” The proclamation stated in part: “Professor Cole was a man of high morals and exemplary character and was an instrumental force as an educator in Carter County. He was truly an inspirational leader among his peers.”

To former students like Kate Watson and Mack Houston, the old grammar school still warmly burns, like the old pot-bellied stoves, in their hearts and memories.

Comments are closed.