There was a time when people suffered from “consumption,” now known as tuberculosis, a debilitating disease that often resulted in certain death for those afflicted.

I vividly recall when one of my childhood friend’s father was diagnosed with TB and was sent to a hospital in Greeneville, TN for a prolonged stay and treatment of the dreaded disease. Sadly, he never returned to his family. Affected people were once sequestered in stuffy rooms with closed windows and given cod-liver oil and cough medicine until death finally offered its relief.

It was not until 1873 that tuberculosis victims had any hope of surviving the malady. Dr. Edward Trudeau was cured of the illness by isolating himself in the remote Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York. The doctor subsequently developed the first sanitariums that promoted a lifestyle change treatment. These special hospitals provided patients with a regimented treatment of fresh air, cold-water bathing, nourishing food, proper exercise and rest.

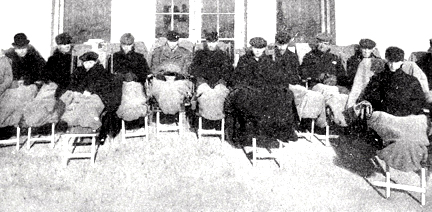

The facilities prescribed rigorous edicts for their patients to follow. Sufferers were kept outdoors all day and not permitted to sleep or sit in a hot room even for a few minutes. Sleeping quarters consisted of open porches, tents in the yard or indoor rooms with the windows fully open. This was enforced in both the sweltering heat of summer and the chilly air of winter. Patients were given extra layers of blankets, fur coats and woolen hoods to stay warm.

Thirty minutes of gentle exercise was administered twice daily; equally important was the need to get plenty of rest. Three full meals per day were served along with a supplemental snack of two raw eggs and two pints of milk served 2-3 hours after each meal. Wine, whisky, beer or tobacco products were absolutely forbidden.

Bathing was in the form of cold sponge baths or a plunge in a frigid body of water. TB sufferers were warned to cover their mouths when coughing or sneezing and to burn the tainted cloths afterward to prevent the spread of bacteria. A positive outlook on life was stressed, which was believed to help strengthen the body. Those inflicted were to look pleasant, act confidently and be cheerful.

Sanitarium treatments, while painfully slow and monotonous, seemed to work. Many patients began to exchange detrimental health for renewed vitality in their bodies. Of 1000 patients in the early stages of TB who sought treatment in a sanitarium, over 600 were cured, 200 others had their disease arrested and some of the remaining 200 were able to do light work. Revitalized patients began giving testimonials about the advantage of enduring the rigors of a sanitarium. Applicants for admission became so numerous that only about one person in 20 was able to secure a room.

Between 1890 and 1910, sanitariums were built in nearly all parts of the civilized world; in the United States alone, some $1.9 billion dollars were spent in erecting them. By 1910, the country had more than a half million people with tuberculosis and fewer than 200 sanitariums to handle them. This statistic forced patients to provide for their treatment at home, which was often not as effective unless they endured the same rigors required of them at a sanitarium.

Today, thanks to advances in medicine, tuberculosis can be cured using a battery of drugs specified by the treating physician. The once plentiful sprawling specialized TB hospitals around the country have mercifully long vanished from the scene.